Canada Gazette, Part I, Volume 152, Number 7: Regulations Amending the Reduction of Carbon Dioxide Emissions from Coal-fired Generation of Electricity Regulations

February 17, 2018

Statutory authority

Canadian Environmental Protection Act, 1999

Sponsoring departments

Department of the Environment

Department of Health

REGULATORY IMPACT ANALYSIS STATEMENT

(This statement is not part of the Regulations.)

Executive summary

Issues: The Government of Canada is committed to reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in Canada to mitigate the impact of climate change. Coal-fired electricity generating units are the highest emitting stationary sources of GHGs and air pollutants in Canada. The proposed amendments to the Reduction of Carbon Dioxide Emissions from Coal-fired Generation of Electricity Regulations (the proposed Amendments) would accelerate Canada's reduction of GHG emissions from electricity generation and help achieve Canada's domestic and international commitments to reduce overall GHG emissions.

Description: The proposed Amendments would require all coal-fired electricity generating units to comply with an emissions performance standard of 420 tonnes of carbon dioxide per gigawatt hour of electricity produced (t of CO2/GWh) by 2030, at the latest. Some units will be required to comply with this performance standard earlier.

Cost-benefit statement: The expected reduction in cumulative GHG emissions resulting from the proposed Amendments is approximately 100 megatonnes (Mt). (see footnote 1) The total expected benefit would be $4.9 billion, including $3.6 billion in avoided climate change damage benefits and $1.3 billion in health and environmental benefits from air quality improvements. The total cost for complying with the proposed Amendments is estimated to be $2.2 billion, resulting in a net benefit of $2.7 billion. More than three quarters of the costs is attributable to compliance measures in Nova Scotia and New Brunswick, with Saskatchewan and Alberta making up most of the remaining costs. Much of the incremental burden for compliance may be passed on to consumers in the form of higher retail electricity rates in affected provinces.

"One-for-One" Rule and small business lens: The proposed Amendments would not change the reporting requirements of the Reduction of Carbon Dioxide Emissions from Coal-fired Generation of Electricity Regulations (the Regulations). As a result, there would be no incremental administrative burden and, therefore, the "One-for-One" Rule does not apply. As the regulated community consists of only large enterprises, the small business lens does not apply.

Domestic and international coordination and co-operation: The proposed Amendments were developed in coordination with provincial and territorial governments, industry, and Indigenous peoples, and are a key commitment of the Pan-Canadian Framework on Clean Growth and Climate Change (the Pan-Canadian Framework). To ensure a just and fair transition to support Canadian workers, Canada will be launching a task force, including labour and business, to hear from workers and communities and will be working with the Government of Alberta on a one-window approach for that province. The Government of Canada is working with the provinces to accelerate the transition to clean electricity. Potential electric transmission intertie projects will be identified through the Regional Electricity Cooperation and Strategic Infrastructure (RECSI) Program. The federal government has also made significant investments in clean growth, such as federal funding for projects under the $21.9 billion Green Infrastructure Fund as well as the Canada Infrastructure Bank. Provincial equivalency agreements may be considered to support provincial transitions from coal towards non-emitting sources of electricity. Equivalency agreements aim to minimize regulatory duplication with provinces, where provincial regimes are found to deliver equivalent or better outcomes than federal regulations. The governments of Canada and Nova Scotia have an equivalency agreement in place for the Regulations. Both governments announced an agreement in principle for a new equivalency agreement that would take the proposed Amendments into consideration. The Canadian government moved ahead of the United States in regulating GHGs from the electricity sector with the Regulations, published in 2012. The generation mix and overall regulatory and market structure of the U.S. electricity sector is significantly different than the Canadian sector, and impacts on Canada's electricity sector are not expected due to its limited trade exposure. In November 2017, the Government of Canada partnered with the Government of the United Kingdom to launch the Powering Past Coal Alliance, a global alliance to phase out coal-fired electricity.

Background

The Regulations were published in the Canada Gazette, Part II, in September 2012. (see footnote 2) The Regulations impose a performance standard (an emissions limit) of 420 t of CO2/GWh of electricity produced by electricity generating units fuelled by coal, coal derivatives and petroleum coke. New units coming online after July 1, 2015, are subject to the performance standard from the start of operation. Units operational prior to 2015 must comply with the performance standard once they have reached the end of their useful life, which is defined as follows in the Regulations:

- Units commissioned before January 1, 1975, are subject to the performance standard after 50 years of operation, or no later than December 31, 2019;

- Units commissioned after December 31, 1974, and before January 1, 1986, are subject to the performance standard after 50 years of operation, or no later than December 31, 2029, whichever date comes first; and

- Units commissioned after December 31, 1985, are subject to the performance standard after 50 years of operation.

The Regulations also include compliance flexibility options to ensure a reliable supply of electricity while achieving the objectives of the Regulations.

In 2015, utilities in Canada generated approximately 580 terawatt hours (TWh) of electricity. (see footnote 3) By 2030, utility generation is expected to rise to 608 TWh. The GHG emissions from the electricity sector are expected to decrease as a whole, from about 79 Mt in 2015 (see footnote 4) to 33 Mt estimated in 2035, about a 46% decrease, mainly due to the declining use of coal as a fuel for electricity generation. This decrease is due in large part to the Regulations.

In 2015, coal-fired units, responsible for 11% of the total electricity generated in Canada, accounted for 75% (63 Mt) of GHG emissions from the sector. By 2030, coal-fired units are expected to generate only 5% of the total electricity generated in Canada, but would account for nearly 55% (27 Mt) of GHG emissions from the sector.

At the twenty-first session of the Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) held in Paris in December 2015, Canada and 194 other countries reached an agreement to fight climate change (the Paris Agreement). The Paris Agreement strengthened the efforts of Parties to the UNFCCC to limit the global average temperature rise to well below 2°C and pursue efforts to limit the increase to 1.5°C. The Paris Agreement was officially ratified by Parliament in October 2016, committing Canada to reducing GHG emissions by 30%, from 2005 levels, by 2030. The goal was agreed to by most provincial premiers at a meeting of First Ministers in March 2016. (see footnote 5)

In December 2016, the Government of Canada released the Pan-Canadian Framework. (see footnote 6) The Government of Canada developed this Framework with provinces and territories, and in consultation with Indigenous peoples. The Pan-Canadian Framework outlines initiatives to achieve emission reductions across all sectors of the economy. New actions for reducing GHG emissions from the electricity sector include a commitment from federal, provincial, and territorial governments to work together to accelerate the phase-out of traditional coal units across Canada by 2030.

The Government of Canada is working with the provinces to accelerate the transition to clean electricity. Potential electric transmission intertie projects will be identified through the Regional Electricity Cooperation and Strategic Infrastructure (RECSI) Program. The federal government has also made significant investments in clean growth, such as federal funding for projects under the $21.9 billion Green Infrastructure Fund as well as the Canada Infrastructure Bank. To ensure a just and fair transition to support Canadian workers, the governments of Canada and Alberta will be launching a task force, including labour and business, to hear from workers and communities.

In November 2017, the Government of Canada partnered with the Government of the United Kingdom to launch the Powering Past Coal Alliance, a global alliance to phase out coal-fired electricity.

In order to support the Government of Canada's commitment under the Paris Agreement, the Department of the Environment (the Department) published a notice of intent (NOI) in the Canada Gazette, Part I, (see footnote 7) that communicated its intent to amend the Regulations to require that all coal-fired units meet the performance standard of 420 t of CO2/GWh by no later than 2030.

Affected units and provincial reduction measures

In 2017, there were 36 coal-fired electricity generating units operating at 16 facilities in five provinces, with a combined generating capacity of approximately 10 000 megawatts (MW).

Of the 36 units operating in 2017, 20 are expected to shut down before 2030, as they will reach their end of life under the Regulations before that year. Another unit is expected to close prematurely before 2030, due to the Alberta Air Emission Standards for Electricity Generation. One unit in Saskatchewan has been equipped with carbon capture and storage technology and will be able to operate past its prescribed end of life. These units would not be affected by the proposed Amendments. As a result, the total number of coal-fired units expected to operate past 2030 is 14, plus one unit that has been equipped with carbon capture and storage.

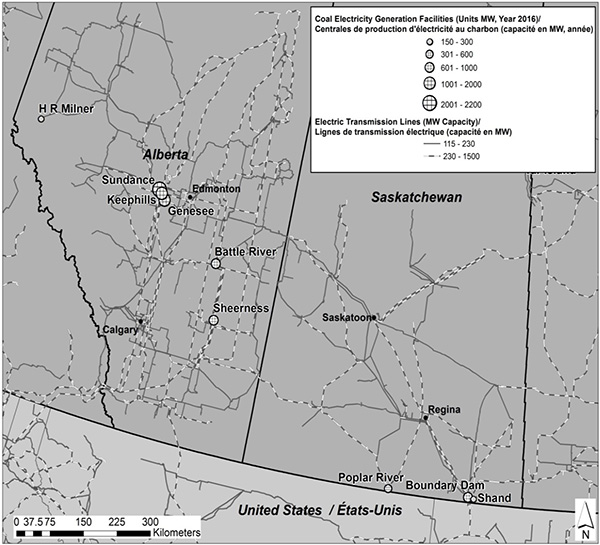

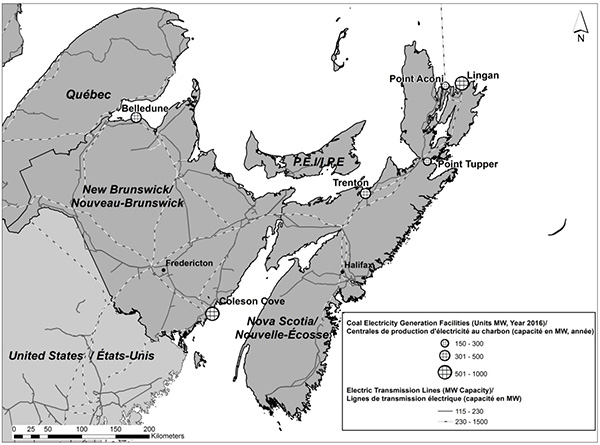

Figures 1 and 2 show the location of coal-fired electricity generating facilities and high-voltage transmission lines in Alberta and Saskatchewan, and New Brunswick and Nova Scotia, respectively.

Figure 1: Coal-fired electricity generating facilities in Alberta and Saskatchewan

Figure 2: Coal-fired electricity generating facilities in New Brunswick and Nova Scotia

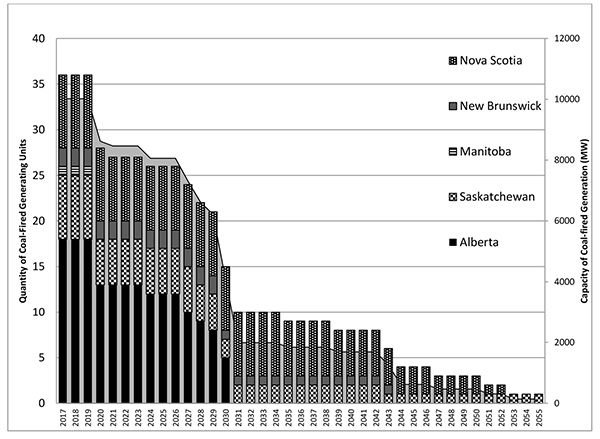

The bar graph in Figure 3 shows the number of units expected to be in operation between 2019 and 2055, in the absence of the proposed Amendments but including provincial policy announcements like Alberta's announced closure of all coal units by the end of 2030. The area graph behind the bars shows the combined capacity of the units in operation. The right, vertical axis shows the combined capacity of coal-fired units operating in megawatts.

Figure 3: Forecast quantity and capacity of coal-fired generating units in Canada

Alberta

The electricity sector in Alberta is a government- organized energy market with privately owned participants. In 2016, the Government of Alberta endorsed a plan by the Alberta Electric System Operator to transition to a new market framework that includes an energy market and a capacity market. In an energy-only market, generators are paid only for the electricity supplied to the grid. With a capacity market framework, generators would be compensated to have capacity ready to dispatch electricity, whether it is supplied or not. The new framework is expected to be in place by 2021. (see footnote 8) In 2017, there were 18 coal-fired generation units operating in Alberta, with a total capacity of 6 286 MW.

In 2015, coal-fired generating plants in Alberta accounted for 48.5% [40.7 Mt CO2 equivalent (CO2e)] (see footnote 9) of all GHG emissions from electric utility generation in Canada. Five of those units, with a combined capacity of 2 106 MW, are expected to shut down at the end of 2030. (see footnote 10)

Under its Climate Leadership Plan (2015), (see footnote 11)Alberta has committed to eliminating GHG emissions from coal-fired electricity generating sources by the end of 2030. This plan also imposes a carbon price of $30 per tonne of CO2 emissions on large industrial emitters (including electricity generators) starting in 2018, while also requiring that 30% of electric utility generation in the province come from renewable sources by 2030.

To reach this objective, Alberta's Renewable Electricity Program (see footnote 12) will add 5 000 MW of wind and solar capacity by 2030, which would replace the equivalent of approximately two thirds of the electricity currently generated by coal. New natural gas-fired units are expected to replace the remaining capacity.

Coal to natural gas conversion

In April 2017, two firms operating coal-fired electricity generating facilities in Alberta announced their intention to convert 11 coal-fired units to natural gas-fired units beginning in 2020. Once converted, they would no longer be subject to the proposed Amendments, but would instead be subject to the proposed Regulations Limiting Carbon Dioxide Emissions from Natural Gas-fired Generation of Electricity. (see footnote 13) The proposed regulations on natural gas-fired electricity generating units have been developed in parallel with the proposed Amendments, and would set a performance standard for all new natural gas-fired generating units as well as coal-fired generating units that have been converted to run on natural gas.

Saskatchewan

The electric utility sector in Saskatchewan is a regulated monopoly with most of the generating and transmission assets owned and operated by SaskPower, a provincial crown corporation. In 2017, there were seven coal-fired electricity generation units operating in Saskatchewan, with a total capacity of 1 535 MW.

In 2015, coal-fired electricity generating facilities in Saskatchewan accounted for 14.1% (11.8 Mt CO2e) (see footnote 14) of all GHG emissions from electric utility generation in Canada. One unit, with a capacity of 120 MW, began operating with carbon capture and storage technology in 2014. The CO2 emission rate for this unit is below the performance standard limit set by the Regulations and it would not be affected by the proposed Amendments.

Two coal-fired generating units are expected to retire in 2020, another in 2028, and two more in 2030. The remaining unit, with a capacity of 276 MW is expected to retire in 2043. Most of the electricity generated by the coal units retiring before 2030 is expected to be generated by a new natural gas-fired generating unit that would begin operating in 2020. New natural gas capacity is expected to be commissioned in 2029 and 2042 to replace coal-fired units as they retire.

In November 2015, SaskPower committed to having 50% of electric generating capacity from renewable sources by 2030, with about 30% generated by wind power. (see footnote 15)

Manitoba

There is one coal-fired generating unit in operation in Manitoba, used only for emergency operations. It is expected to shut down permanently in 2020.

New Brunswick

The electric utility generation sector in New Brunswick is a regulated monopoly with NB Power, a provincial Crown corporation, responsible for generation, transmission and distribution of most electricity in the province. In 2015, coal or petroleum coke-fired electricity generating units in New Brunswick accounted for 3.5% (2.9 Mt CO2e) (see footnote 16) of all GHG emissions from electric utility generation in Canada.

In 2017, New Brunswick had two coal-fired electricity generating units in operation with a total capacity of 837 MW. One of the two units, with a capacity of 357 MW is fuelled by petroleum coke with heavy fuel oil and is expected to shut down in 2029, whereas the remaining unit, with a capacity of 480 MW, is expected to shut down in 2044.

In 2015, New Brunswick passed regulations under its Electricity Act that require that 40% of in-province electricity sales come from renewable sources by 2020. Until then, in-province electricity sales from renewable sources must meet or exceed the 2012–2013 proportion, about 28%. (see footnote 17)

Nova Scotia

The electricity sector is a regulated monopoly in Nova Scotia, with most electricity generation and transmission assets owned by Nova Scotia Power Inc., a privately owned utility.

In 2017, Nova Scotia had eight coal-fired electricity generation units, with a total capacity of 1 247 MW. Under the existing regulation, six of these eight units have end-of-life dates before 2030, but Nova Scotia entered into an equivalency agreement with the federal government, which suspended the application of the Regulations in the province. (see footnote 18) As a result, seven of the eight units (1 094 MW) are expected to operate beyond 2030.

In 2015, coal-fired units in Nova Scotia accounted for 7.2% (6 Mt CO2e) (see footnote 19) of all GHG emissions from electric utility generation in Canada.

As part of the equivalency agreement, Nova Scotia amended its Environment Act in 2013 to include GHG emission caps for electricity utility generation. Total GHG emissions from electricity utility generation are capped at 4.5 Mt CO2e, for the year 2030. Under its 2009 Climate Change Action Plan, 2009 Energy Strategy, and 2010 Renewable Electricity Plan, Nova Scotia committed to transitioning from coal to more renewable energy sources. These policies required Nova Scotia Power Inc. to obtain 25% of electricity from renewable energy sources by 2015, and to increase this minimum to 40% by 2020.

Issues

GHG emissions pose a risk to the health, environment, and overall welfare of Canadians by contributing to climate change. Coal-fired electricity generating units are the highest emitting stationary sources of harmful GHGs and air pollutants in Canada, accounting for nearly 9% of total national GHG emissions in 2015, 23% of total national emissions of sulphur oxides, 6% of nitrogen oxides, and 17% of mercury. (see footnote 20) Although Canada has taken action to reduce GHG and air pollutant emissions from coal-fired electricity generating units, making a meaningful contribution to achieving its Paris Agreement commitment would require these reductions to occur earlier than would be expected under existing Regulations. The proposed Amendments are one of many actions identified in the Pan-Canadian Framework for achieving Canada's Paris Agreement commitment.

Objectives

The objective of the proposed Amendments is to ensure that the permanent transition from high-emitting electricity sources to low- or non-emitting sources is achieved by 2030, which would further contribute to the protection of the environment and the health of Canadians, as well as help Canada fulfill its Paris Agreement commitment to reduce its 2005 levels of GHG emissions by 30% by 2030.

Description

Under the Regulations, the performance standard of 420 t of CO2/GWh of electricity produced applies to new coal-fired electricity generating units commissioned after July 1, 2015, and existing units that have reached their end-of-life date as defined by the Regulations. The proposed Amendments would require all new and existing units to comply with the performance standard after 50 years of operation, or by 2030, whichever comes first.

Regulatory and non-regulatory options considered

In order to achieve the objective of ensuring a permanent transition from high-emitting to low- or non-emitting sources of electricity generation by 2030, the Department considered the following options:

Status quo approach

Emissions of CO2 from coal-fired generating units are regulated under the Regulations, whereby high-emitting coal-fired units could continue operating beyond 2040. Allowing high-emitting coal-fired units to operate would require other sectors to reduce GHG emissions in order to meet Canada's 2030 emission target. Federal and provincial governments would be required to develop policies to reduce emissions from other sectors where the marginal abatement cost would be much higher than the cost for emission reductions from the coal-fired electricity generating units. This would result in an unnecessary loss of social welfare.

Voluntary measures

Voluntary (or alternative) measures are less prescriptive than a regulatory approach. For example, under the Canadian Environmental Protection Act, 1999 (CEPA), a Pollution Prevention Plan (P2 Plan) is a voluntary agreement for the use of processes, practices, materials, products, substances or energy that avoids or minimizes the creation of pollutants and waste and reduces the overall risk to the environment or to human health.

The Risk Management Objective (RMO) identified in a P2 Plan planning notice is not enforceable under CEPA. Persons subject to a P2 Plan planning notice must consider the RMO in the preparation and implementation of their plans, but they would not be held accountable under the law if it is not met. P2 Plan planning notices are therefore not as prescriptive nor as stringent as regulations. A regulatory approach would ensure that the requirements of the proposed Amendments are met and that such reductions help contribute to Canada's commitment under the Paris Agreement.

A P2 Plan could not provide assurance of significant emission reductions in the desired time frame, nor the level of certainty needed to support industry investment in lower- or non-emitting sources of electricity generation.

Cap-and-trade system

In a cap-and-trade system, a mandatory limit is set for allowable cumulative emissions from the covered community. Participants then trade emission permits (or allowances) in a market system to maximize profits without polluting above the cap.

Cap-and-trade systems are applied to GHG emissions in Ontario (see footnote 21) and Quebec. (see footnote 22) These are stand-alone regional cap-and-trade programs that may eventually be integrated with each other and other markets in North America, through the Western Climate Initiative, for example. (see footnote 23) The European Union's Emission Trading System has been operating since 2005 and is the world's largest GHG emission trading scheme.

A cap-and-trade system would not achieve the objective of a complete phase-out of coal-fired electricity generation units in Canada within the desired time frame, nor would it provide the necessary policy certainty required to support industry investments in lower- or non-emitting sources of electricity generation.

Pricing of GHG emissions

The first pillar of the Pan-Canadian Framework is pricing carbon pollution across Canada, and a key element of nationwide carbon pricing is the federal carbon pricing backstop. (see footnote 24) Coal-fired electricity generating units would be subject to carbon pricing in all provinces with the federal backstop system in place, starting in 2018. Even though provincial and federal carbon pricing systems are either in place or being developed, the proposed Amendments have been included in the Pan-Canadian Framework as a complementary climate action that would achieve deeper, faster emission reductions than carbon pricing alone.

Existing and planned carbon pricing systems implemented by provincial and federal governments would reduce emissions from coal-fired electricity generation units, but the complete phase-out of conventional coal-fired electricity would be no sooner than in the baseline scenario.

Regulated approach under CEPA

Reducing GHG emissions to the level required to meet the 2030 target will require reductions from all sectors of the economy. The proposed Amendments are one of many measures taken to meet this target. The regulated approach leverages the existing regulatory framework to ensure that the permanent transition from high-emitting coal-fired electricity generating sources to lower- or non- emitting sources is accomplished within the desired time frame. It is designed to provide regulatory certainty to allow electric utility generators to adjust capital investment plans.

Benefits and costs

Between 2019 and 2055, the expected reduction in GHG emissions (see footnote 25) from electric utility generation as a result of the proposed Amendments is approximately 100 Mt, which would result in avoided climate change damages valued at $3.6 billion. (see footnote 26) Another benefit of the proposed Amendments would be a reduction in air pollutant emissions, which would result in air quality improvements valued at $1.3 billion, bringing the total benefit to $4.9 billion. The total cost for complying with the proposed Amendments is $2.2 billion, resulting in a net benefit of $2.7 billion.

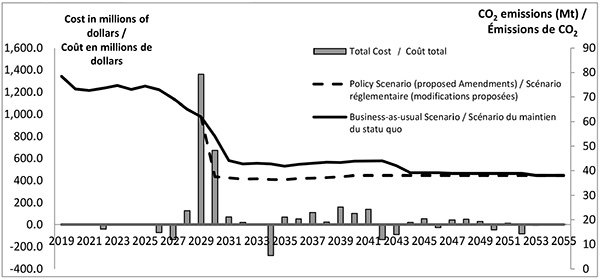

As shown in Figure 4, the most significant costs would be carried around 2029 for commissioning new capacity to replace coal-fired generating units and in 2030 for decommissioning units that have reached their amended end of life. Those costs would be partly offset later, by the avoided costs of replacement capacity, had those units operated until their end of life. Early replacement would also result in incrementally higher annual generating costs in subsequent years, as utilities would be required to supply electricity from a more expensive source.

Figure 4: Baseline scenario and policy scenario CO2 emissions and compliance costs by year

Analytic framework

The benefits and costs associated with the proposed Amendments have been assessed in accordance with the Treasury Board Secretariat (TBS) Canadian Cost-Benefit Analysis Guide, (see footnote 27) which includes identifying, quantifying and, where possible, monetizing the impacts associated with the policy. The incremental impacts of the proposed Amendments are determined by comparing the electricity sector without the proposed Amendments (the baseline scenario), and with the proposed Amendments (the policy scenario). The baseline scenario includes provincial regulations, such as Alberta's Climate Leadership Plan, and programs that influence electricity generation in the provinces, including their announced regulatory timelines and application of a price on carbon.

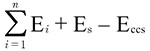

The key impacts of the proposed Amendments are demonstrated in the logic model below (Figure 5). The central analysis considers the benefits and costs of replacing generating capacity earlier in the policy scenario than in the baseline scenario. The difference between the two is reported as the net benefits of the proposed Amendments.

Accelerating the closure of coal-fired generating units would reduce GHG and air pollutant emissions from the electricity sector, which would result in avoided climate change damage in the future and improved air quality. Compliance with the proposed Amendments would result in higher costs to supply customers with electricity in the policy scenario relative to the baseline scenario. Consumers would respond to higher prices by using less electricity in the policy scenario than in the baseline scenario, which would reduce consumer welfare. The compliance costs to electricity providers and welfare loss of consumers would be the social cost of the proposed Amendments.

| A coal unit reaches its regulated end of life and must comply with the 420 t of CO2/GWh performance standard. | → | Reduced GHG and air pollutant emissions | → | Avoided climate change damage / Improved air quality | → | Social benefit | ||||||

| ↓ | ||||||||||||

| Shut down and replace with generation from non-coal-fired source. Three compliance strategies to respond to lost generation. | → | Build replacement capacity | → | Compliance costs | → | Social cost | ||||||

| → | Higher retail prices | |||||||||||

| → | Increase generation from existing non-coal units | → | ↓ | |||||||||

| → | Increase imports / Reduce exports | → | → | Reduced electricity use | → | |||||||

The baseline and policy scenarios were based on Canada's 2016 greenhouse gas emissions reference case (see footnote 28) and updated through consultation with stakeholders, as well as with counterparts in federal departments and provincial ministries.

The modelled scenarios were based on information available in March 2017 in order to allow sufficient time for multiple stages of modelling and data processing. The announcement of the intent to convert coal-fired units in Alberta to natural gas-fired units was made after March 2017; therefore, conversions have not been incorporated into the baseline scenario. For the Canada Gazette, Part II, publication, the Department will reassess and update the baseline scenario.

The underlying assumption of the policy scenario is that electric utilities would respond to the proposed Amendments in a manner consistent with cost minimization behaviour of the firm, while accounting for system operation requirements and observing all other existing or imminent rules and regulations.

The time frame considered for this analysis is 2019–2055. This is based on the expectation that the proposed Amendments would be published in the Canada Gazette, Part II, by the end of 2018. The end year for the analysis is meant to capture the full impact of replacing all coal units early, since the last coal-fired generating unit is not expected to retire until 2053 in the baseline scenario. As shown in Figure 4, few costs are expected prior to 2029.

Any regulation that affects the ability of utilities to supply electricity will indirectly affect many parts of the economy. Higher electricity prices will alter the behaviour of electricity-dependent individuals and firms. Nonetheless, the scope of the central analysis is limited to the impact on costs for, and emissions from, the electricity sector, with consideration for how consumer welfare would be affected by the resulting higher retail prices for electricity. (see footnote 29)

Compliance strategies

The proposed Amendments would accelerate the regulated end of life for conventional coal-fired electricity generating units to the end of 2029. Electricity generating firms would respond with one of the following three options to replace the lost generation from coal-fired electricity generating units:

- (a) build emission-compliant replacement capacity;

- (b) increase imports and/or decrease exports; or

- (c) increase generation from existing non-coal-fired units.

This analysis assumes that utilities would respond to lost generation from coal-fired electricity units with the same strategy in both the baseline and the policy scenario. For example, where the generation from a coal-fired generation unit is expected to be replaced with generation from a newly constructed natural gas-fired unit in the baseline scenario, then it would be expected to be replaced by a newly built natural gas unit in the policy scenario as well.

Alberta

In the baseline scenario, coal-fired units in Alberta would be shut down by December 31, 2030, in response to Alberta's Climate Leadership Plan. In the policy scenario, all coal units in Alberta would shut down at the end of 2029. This would create a 12-month gap between the baseline and policy scenarios. Any costs, benefits and emission reductions attributable to the proposed Amendments would occur because of the difference between the baseline and policy scenarios, i.e. the 12-month earlier shutdown in the policy scenario versus the baseline scenario. The foregone generation from coal-fired units would, in part, be replaced through increased generation from existing utility generating units, with some additional input from industrial cogeneration units, although a small change in the timing of some capital investments is expected. Since cogeneration units are almost all fuelled by natural gas, this would result in higher fuel spending for that year.

Saskatchewan

Saskatchewan is expected to build additional natural gas-fired capacity in 2029 to replace the coal unit that would have operated until 2043 in the baseline scenario. A natural gas-fired generating capacity is already expected to be built in that year to replace coal units closing in 2029 in the baseline scenario. The new units would have a greater capacity than in the baseline scenario. This would result in incrementally higher generating costs between 2030 and 2043. The capital costs would be higher in 2029 to replace the coal unit early, but avoided in 2043 since it would have been decommissioned 13 years earlier.

New Brunswick

New Brunswick is a regional electricity hub, with a transmission grid strongly interconnected to the Maritimes, Quebec and New England. The province is expected to take advantage of its existing transmission capacity and replace lost generation from coal-fired units with hydroelectricity purchased from Quebec.

Historically, New Brunswick has been a net exporter of electricity. However, this is expected to change dramatically over the next two decades as generating capacity is expected to shut down without being fully replaced.

In the baseline scenario, approximately 1 100 MW of generating capacity in New Brunswick is expected to shut down around 2030. This would lead to a change in the net outflow of electricity from around 1 200 GWh in 2029, to a net inflow of 500 GWh in 2030. This trade deficit is expected to grow to around 3 000 GWh per year by 2044 when the coal-fired unit retires.

In the policy scenario, the closure of the coal-fired unit would lead to approximately 1 580 MW of generating capacity shutting down in 2030. Electricity generated by the coal-fired unit would be replaced by purchased power from outside the province. This is expected to increase the net inflow of electricity to nearly 3 600 GWh in 2030 (3 100 GWh more than the baseline scenario).

In both the baseline and policy scenarios, the province would build some new natural gas capacity to maintain a reserve margin; however, the high price of natural gas would make it more cost effective to import hydroelectricity from Quebec, so the utilization rate for these units would be low. Importing electricity from Quebec would be more expensive than generating it with a coal-fired power plant, but less expensive than generating it with a natural gas-fired unit.

Increasing imports of hydroelectricity from Quebec and reducing reliance on costlier fossil fuel generation lowers the spot price of electricity at base load times, which lowers the return on building intermittent generation in New Brunswick and ultimately reduces the construction of wind in the policy scenario.

Nova Scotia

In the baseline scenario, the Nova Scotia equivalency agreement is assumed to extend indefinitely beyond 2030, whereas it would end in 2030 in the policy scenario.

In the modelled scenarios, Nova Scotia would replace almost all its coal-fired electricity with electricity generated by new natural gas-fired units. There would also be some adjustment of the electricity trade flows in and out of the province. Trade with Newfoundland and Labrador, through the Maritime Link, is expected to reach maximum capacity in the baseline and policy scenarios prior to 2030. However, Nova Scotia would send less electricity into New Brunswick in the policy scenario than in the baseline scenario.

Incremental impacts of compliance

More than 99% of the incremental cost of the proposed Amendments would occur in the four provinces directly affected by the regulations, shown in Table 12 in the "Distributional impact analysis" section below. Costs in other provinces are mostly related to changes in interprovincial electricity trade. Most tables include only affected provinces. Therefore, totals may not sum perfectly due to impacts in other provinces. Since benefits from air quality improvements are not limited to the province of origin, a row for the rest of Canada is included in those tables.

Benefits of compliance

The cumulative benefit in Canada of the emission reductions from the proposed Amendments is valued at $4.9 billion (2019–2055).

Benefits of the proposed Amendments are from avoided global climate change damage and improved air quality due to reduced air pollutant emissions. Benefits from reduced air pollutants (calculated at the provincial level) include health benefits and environmental benefits. The proposed Amendments would reduce GHG emissions from electricity generation by 100 Mt of CO2e between 2019 and 2055 versus the baseline scenario. The avoided climate change damage from these reductions is valued at $3.6 billion using the Department's Social Cost of Greenhouse Gas Estimates. (see footnote 30) The proposed Amendments would also result in the reduction of emissions of many criteria air pollutants. The most significant reduction in emissions would be 555 kilotons (kt) of sulphur oxides (SOx) and 206 kt of nitrogen oxides (NOx) between 2019 and 2055. These criteria air pollutants have been shown to adversely affect the health of Canadians, through direct exposure and through the creation of smog (including particulate matter and ground-level ozone). The health benefits from reduced air pollutant emissions and avoided human exposure to mercury are valued at $1.2 billion. Environmental benefits, such as increased crop yields, reduced surface soiling, and improvement in visibility, is valued at $40 million.

GHG emission reductions

Almost all (>99%) of GHG emission reductions from the proposed Amendments would be from reductions in CO2 emissions. There would also be reductions in nitrous oxide (N2O) emissions, but a small increase in methane (CH4) emissions. These emissions are valued separately using the Social Cost of GHG Estimates. However, for reporting purposes, emissions of N2O and CH4 are converted to CO2e using 100-year Global Warming Potentials (see footnote 31) from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Fourth Assessment Report. (see footnote 32) Table 1 shows the expected reduction in GHG emissions attributable to the proposed Amendments.

| 2019–2025 | 2026–2030 | 2031–2035 | 2036–2040 | 2041–2045 | 2046–2050 | 2051–2055 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alberta | 0.0 | 9.7 | 0.9 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 10.6 |

| Saskatchewan | 0.0 | 1.3 | 6.4 | 6.7 | 2.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 17.0 |

| New Brunswick | 0.0 | 2.6 | 11.2 | 11.4 | 6.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 31.9 |

| Nova Scotia | 0.0 | 2.7 | 12.5 | 11.2 | 8.5 | 4.3 | 1.6 | 40.7 |

| Total | 0.0 | 16.3 | 30.9 | 29.4 | 17.9 | 4.3 | 1.6 | 100.5 |

Social cost values are used to estimate the monetary value, in a given year, of the worldwide damage that would occur over the coming decades from each additional tonne of GHGs emitted into the atmosphere. This analysis uses the central values for social cost of CO2, CH4, and N2O. A valuation using the 95th percentile (P95) value, which represents a low-probability, high-cost climate change future, is presented in the sensitivity analysis. Table 2 shows the central and 95th percentile social cost values for CO2, CH4, and N2O at the start of each decade.

| GHG | 2020 | 2030 | 2040 | 2050 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Central | P95 | Central | P95 | Central | P95 | Central | P95 | |

| CO2 | 47 | 195 | 58 | 249 | 68 | 298 | 79 | 338 |

| CH4 | 1,348 | 4,043 | 1,825 | 5,858 | 2,343 | 7,848 | 2,865 | 9,566 |

| N2O | 16,830 | 56,354 | 21,272 | 73,168 | 25,867 | 90,445 | 30,812 | 108,620 |

Benefits from reduced air pollutant emissions

To assess the potential health and environmental benefits resulting from air pollutant emission reductions, ECCC's Meteorological Service of Canada ran the A Unified Regional Air-quality Modelling System (AURAMS) atmospheric model to determine how the emission decrease would affect ambient air quality (i.e. the air that Canadians breathe). Health Canada then used the Air Quality Benefits Assessment Tool (AQBAT) (see footnote 33) to determine how improvements in ambient air quality would affect the health of Canadians.

Based on changes in local ambient air quality, AQBAT estimates the likely reductions in average per capita risks for a range of health impacts known to be associated with air pollution exposure. These changes in per capita health risks are then multiplied by the affected populations in order to estimate the reduction in the number of adverse health outcomes across the Canadian population. AQBAT also applies economic values drawn from the available literature to estimate the average per capita socio-economic benefits of lowered health risks.

Environmental benefits were estimated using the Air Quality Valuation Model (AQVM2). This model estimates how changes in ambient air quality will impact three different endpoints being exposed to atmospheric pollution: crop productivity, surface soiling, and visibility. More precisely, AQVM2 relies on biological dose-response functions to measure increases in sales revenue from enhanced crop productivity associated with reduced ground-level ozone, as well as willingness-to-pay estimates to measure Canadian households' welfare improvement from reduced surface soiling and increased visibility (i.e. windows), both associated with lower levels of particulate matter.

Benefit estimates reflect not only the emission reductions, but also the atmospheric conditions and endpoint (population or croplands) exposure to these pollutants. Population density, wind direction, and atmospheric conditions play a critical role in smog formation. For instance, emission reductions at facilities that are located upwind of large population centres or extensive croplands can have a greater impact than similar emission reductions at facilities in remote or downwind locations. Consequently, benefit estimates in a province may not necessarily be proportional to emission reductions in that same province. In addition, environmental benefits in some provinces may be partly attributable to reductions of emission releases from adjacent provinces, because pollutants can travel over longer distances. The AURAMS, AQBAT, and AQMV2 models were run for the years 2030 and 2035. In order to estimate the benefits for the remaining years, pro-rating techniques were used. Significantly more emissions would be reduced in 2030, relative to any other year in the analytical time frame. Since the variability in annual emission reductions was estimated to be lower between 2031 and 2055, the annual environmental benefits in this period were proxied by pro-rating the 2035 values by the proportion of pollutant emission reductions (mainly composed of SOx and NOx) for each year between 2031 and 2034, and between 2036 and 2055. (see footnote 34)

Improved health outcomes

Total health benefits are estimated be around $1.2 billion for the 2019 to 2055 period.

The human health impacts and resulting socio-economic benefits are highly dependent on population proximity to the source of emissions from coal-fired electricity generation. It is the population exposure to changes in air quality, and not simply the absolute changes in particulate matter (PM) and ozone levels, which determines the health benefits of the proposed Amendments. For this reason, the areas that experience the largest health benefits, and the areas that experience the largest air quality improvements, are not necessarily the same.

The health benefits covered in the analysis include a wide range of health outcomes linked with air pollution. These range from health outcomes such as asthma episodes and minor breathing difficulties to much more serious impacts such as visits to the emergency room and hospitalization for respiratory or cardiovascular problems. Air pollution also increases the average per capita risk of death. While the changes in individual risk levels are small, they apply to large populations; these individual risk reductions translate into large social benefits. Table 3 shows some of the estimated changes in cumulative health outcomes as a result of the Regulations.

Health benefits resulting from improved air quality under the proposed Amendments would have a present value of roughly $440 million in 2030. This includes a large benefit in Alberta ($310 million). The benefits estimated in Alberta attributable to the proposed Amendments do not extend past 2030, as coal-fired units would shut down by 2031 in the baseline scenario. In 2035, the estimated health benefits across Canada are expected to be lower, approximately $56 million. The largest benefit is estimated in Nova Scotia ($26 million).

Table 3 shows the estimated total present value of the improvement in social welfare, expressed in economic (dollar) terms, for all health outcomes over 2019 to 2055. The present value of the health benefits is estimated at $1.2 billion, with the largest benefits in Nova Scotia, followed by Alberta, New Brunswick and Saskatchewan. (see footnote 35)

The reductions in ambient PM2.5 account for approximately 60% of the health benefits from the proposed Amendments. This is primarily from secondary formation of PM2.5 from reductions in other primary pollutants, such as NOx and SOx. Ozone improvements account for about 40% of the health benefits. Benefits are driven by a reduction in premature mortality risk, largely because of reductions in ambient PM levels.

The values shown in Table 3 are socio-economic values associated with changes in health status, or changes in health risks. These values are derived using a social welfare approach. (see footnote 36) The values in the table are not estimates of medical treatment costs, nor are they estimates of changes in worker productivity or GDP. Rather, the values in the table are estimated measures of improvement in quality of life, resulting from better health. By far the most significant impact of the air quality improvements, in terms of quality of life, is a reduction in the risk of premature mortality. Reductions in mortality risk account for approximately 95% of the estimated social welfare. (see footnote 37)

| Region | Estimated changes in cumulative health outcomes as a result of the Regulations | Present value in 2017 of total avoided health outcomes (millions of 2016 dollars) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Premature Mortalities | Asthma Episodes |

Days of Breathing Difficulty and Reduced Activity | Ozone Related | PM2.5 Related | Total (Includes Additional Pollutants) |

|

| Alberta | 56 | 14 000 | 66 000 | 90 | 210 | 310 |

| Saskatchewan | 10 | 1 400 | 9 400 | 4 | 40 | 50 |

| New Brunswick | 36 | 4 100 | 23 000 | 70 | 80 | 160 |

| Nova Scotia | 89 | 8 000 | 58 000 | 70 | 300 | 400 |

| Rest of Canada | 73 | 12 000 | 38 000 | 230 | 100 | 320 |

| Total | 260 | 40 000 | 190 000 | 470 | 730 | 1,200 |

Numbers have been rounded to show a maximum of two significant digits. Columns and rows may not necessarily sum to totals due to rounding.

Mercury reductions from the electricity sector

In addition to reductions in NOx, SOx and PM emissions, the proposed Amendments are expected to reduce mercury emissions from the electric utility sector by 1.4 tonnes between 2019 and 2055. Mercury that enters the ecosystem can enter the food chain and can have toxic impacts on humans and wildlife. Reducing mercury emissions from power plants is, therefore, expected to result in human health benefits. These health benefits have been estimated at approximately $5 million. (see footnote 39)

Environmental benefits

Particulate matter may accumulate on surfaces and alter their optical characteristics, making them appear soiled or dirty, while particulate matter in suspension in the air can block and scatter the direct passage of sunlight to reduce visibility. In addition, high concentrations of ozone can affect crops by reducing their biomass and increasing their vulnerability to stressors such as diseases. Therefore, better air quality may result in reduced surface soiling, improvement in visibility, which may positively impact the general welfare of Canadians, as well as tourism, and increase crop yields. The quantified environmental benefits resulting from the proposed Amendments are estimated to be about $40 million. The welfare of residential households associated with improvement in visibility is valued at $29.6 million. Higher crop yields and avoided household cleaning costs account for $8.2 million and $2.5 million, respectively. Nova Scotia would receive the largest portion of these benefits, which is consistent with its large reduction in emissions.

Table 4 below presents the estimated environmental benefits, for each modelled impact and province experiencing significant reductions in emissions under the proposed Amendments, with the other provinces/territories aggregated as the "Rest of Canada."

| Environmental impact Economic indicator |

Agriculture Change in Sales Revenues for Crop Producers |

Soiling Avoided Costs for Households |

Visibility Change in Welfare for Households |

Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alberta | 3 | 1 | 5 | 9 |

| Saskatchewan | 1 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| New Brunswick | 0 | 0 | 3 | 4 |

| Nova Scotia | 0 | 1 | 11 | 12 |

| Rest of Canada | 3 | 0 | 9 | 12 |

| Total | 8 | 2 | 29 | 40 |

Totals may not add up due to rounding.

The estimate above for total environmental benefits should be considered to be conservative, because several benefits could not be quantified. The reduction in concentrations of ozone and PM may benefit the health of forest ecosystems and may reduce the risk of illness or premature death within sensitive wildlife or livestock populations. This would potentially result in reduced treatment costs and economic losses for the agri-food industry. However, due to limitations in data and methodology, these benefits could not be quantified in the AQVM2 model.

Compliance costs

The incremental cost of the proposed Amendments is estimated to be $2.2 billion between 2019 and 2055.

Total spending on electric utility generation was calculated for each year and each province in Canada for the baseline and the policy scenarios. The values for costs presented in this analysis are the difference between the two scenarios.

Incremental costs associated with the proposed Amendments are divided into three categories: capital costs, supply costs, and reduced electricity use. Almost all of the incremental cost is attributable to additional fuel costs or purchased power from another region.

Capital costs

Capital costs represent a one-time expenditure for building replacement capacity, refurbishing existing units, and decommissioning units that have reached their end of life. Costs for replacement capacity and decommissioning would be seen in both the baseline and policy scenarios, but at different times. Refurbishment costs are investments intended to restore the operational integrity of the unit. When a coal-fired unit is shut down early, refurbishment costs would be avoided.

There are large up-front capital costs for compliance between 2026 and 2030 as replacement units are built and coal units are decommissioned. This is offset by avoided construction in later years and avoided refurbishment costs to keep coal-fired generating units running beyond 2030.

Overall, the net capital costs of compliance with the proposed Amendments would total $85 million, as seen in Table 5. The values in Table 5.A (net construction costs), Table 5.B (refurbishment costs) and Table 5.C (decommissioning costs) sum to the totals presented in Table 5.

| 2019–2025 | 2026–2030 | 2031–2035 | 2036–2040 | 2041–2045 | 2046–2050 | 2051–2055 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alberta | 0 | 173 | −167 | −1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 |

| Saskatchewan | 0 | 297 | −53 | −1 | −195 | 13 | 0 | 61 |

| New Brunswick | 0 | 241 | −171 | −34 | −127 | 11 | 0 | −80 |

| Nova Scotia | −40 | 949 | −196 | −184 | −202 | −110 | −116 | 101 |

| Total | −40 | 1,660 | −587 | −220 | −525 | −86 | −116 | 85 |

Totals may not add up due to small impacts in provinces not directly affected by the proposed Amendments.

Cost to build replacement capacity

The total cost for commissioning replacement generating capacity is approximately $466 million.

The price per kilowatt (kW) of commissioning new generating capacity is taken from the National Renewable Energy Laboratory 2015 Standard Scenarios Annual Report (see footnote 40) and then adjusted for each province through consultation with stakeholders. For example, the undiscounted expected 2030 price of natural gas combined cycle generating capacity is $1,748/kW in Alberta and Saskatchewan, $1,624/kW in Nova Scotia, and $1,020/kW in New Brunswick.

Table 5.A shows the expected incremental construction costs for new generating capacity. Positive values mean that utilities are expected to spend more in the policy scenario than in the baseline scenario. Negative values mean that new construction costs are avoided in the policy scenario. In the case of Nova Scotia, over $1 billion would be spent in the policy scenario to replace coal-fired generating units with natural gas-fired generating units by 2030. Since these units would be gradually replaced in the baseline scenario, these replacement costs are avoided in subsequent years.

New Brunswick builds approximately 70 MW less wind capacity in the policy scenario than in the baseline scenario, which results in $18 million savings. In the baseline scenario, the province is expected to have approximately 350 MW of wind capacity by 2035. In the policy scenario, only 280 MW of wind capacity is built by 2035, and none is added later.

| 2019–2025 | 2026–2030 | 2031–2035 | 2036–2040 | 2041–2045 | 2046–2050 | 2051–2055 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alberta | 0 | 9 | −7 | −1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Saskatchewan | 0 | 275 | −2 | −1 | −181 | 0 | 0 | 92 |

| New Brunswick | 0 | 204 | −85 | −34 | −102 | 0 | 0 | −18 |

| Nova Scotia | 0 | 1,073 | −129 | −116 | −186 | −157 | −102 | 383 |

| Total | 0 | 1,561 | −224 | −152 | −470 | −157 | −103 | 455 |

Totals may not add up due to small impacts in provinces not directly affected by the proposed Amendments.

Refurbishments

The proposed Amendments would result in $424 million in net avoided refurbishment costs. This total includes $502 million in avoided refurbishment costs for coal-fired generating units shut down early, as well as $78 million in additional refurbishment costs for natural gas-fired units commissioned to replace coal-fired units. Coal-fired electricity generating units are designed to operate for about 25 to 30 years; however, refurbishment can permit lifespans up to 50 years or longer. Refurbishment costs vary according to the scope and intensity of the repairs, the life extension being sought and the type of parts that have to be replaced.

The first refurbishment usually occurs after about 20 years of operation to prevent unplanned outages. An initial refurbishment to extend a unit's life by another 20 years is assumed to cost $1,008/kW, whereas one that would grant an extension of 15 years would cost only $504/kW. (see footnote 41) Subsequent refurbishments are expected to achieve shorter life extensions but cost less because even though older units have higher levels of thermal stress, they have a smaller subset of parts that must be replaced to address this issue. Refurbishment costs for units that have already had at least one refurbishment are therefore assumed to be 60% of the above values.

Since the proposed Amendments would reduce the operational life of affected units, major refurbishments would be avoided. In some cases, utilities would choose to undertake less extensive refurbishments prior to 2030, since the unit would only operate for another 6 or 7 years, as opposed to another 20 years. For example, one unit in Nova Scotia is expected to require refurbishments in 2022. In the baseline scenario, an extensive refurbishment would enable the unit to operate for another 20 years before it would need to be refurbished again. In the policy scenario, the refurbishment would be less extensive, since the unit would be shut down after eight years. This would result in approximately $40 million in avoided refurbishment costs.

Natural gas-fired units would be refurbished after about 20 years in operation. The estimated average refurbishment cost of a natural gas combined cycle unit would be about $126/kW. Table 5.B shows these costs from the units that would otherwise be invested in refurbishment.

| 2019–2025 | 2026–2030 | 2031–2035 | 2036–2040 | 2041–2045 | 2046–2050 | 2051–2055 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alberta | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Saskatchewan | 0 | 0 | −51 | 0 | 0 | 13 | 0 | −38 |

| New Brunswick | 0 | 0 | −86 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 0 | −75 |

| Nova Scotia | −40 | −209 | −57 | −59 | 0 | 54 | 0 | −311 |

| Total | −40 | −209 | −194 | −59 | 0 | 78 | 0 | −424 |

Decommissioning costs

The cost of decommissioning units is expected to be $54 million. Units are expected to be decommissioned the year they cease operating. In the policy scenario all decommissioning costs for coal-fired units would be carried in 2030. These costs would then be avoided in the future. Decommissioning costs are assumed to be $117/kW when scrap material credit is taken into account. This cost accounts for activities such as dismantling boilers, demolishing structures and asbestos remediation. It also includes project expenses such as securing permits and insurance, renting heavy equipment and hiring operating engineers.

Since the real cost does not change over time, the incremental impact is the time value of money spent at different periods.

| 2019–2025 | 2026–2030 | 2031–2035 | 2036–2040 | 2041–2045 | 2046–2050 | 2051–2055 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alberta | 0 | 164 | −159 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| Saskatchewan | 0 | 22 | 0 | 0 | −15 | 0 | 0 | 7 |

| New Brunswick | 0 | 37 | 0 | 0 | −25 | 0 | 0 | 13 |

| Nova Scotia | 0 | 85 | −10 | −9 | −16 | −7 | −13 | 29 |

| Total | 0 | 308 | −169 | −9 | −56 | −7 | −13 | 54 |

Electricity supply costs

The additional cost of supplying customers with electricity in Canada would be $1,894 million between 2019 and 2055. Electricity supply costs are ongoing costs associated with delivering electricity to customers. Supply costs consist of operations and maintenance (O&M) [the non-fuel cost for generating electricity], fuel, out of province purchases (the price paid to import electricity), and lost revenue from foregone exports. These are discussed below. The values in tables 6.A (changes to electricity trade with other regions), 6.B (operating and maintenance costs), and 6.C (fuel costs), sum to the values presented in Table 6.

| 2019–2025 | 2026–2030 | 2031–2035 | 2036–2040 | 2041–2045 | 2046–2050 | 2051–2055 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alberta | 0 | 167 | −48 | −5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 115 |

| Saskatchewan | 0 | 18 | 73 | 60 | 21 | 0 | 0 | 172 |

| New Brunswick | 0 | 35 | 228 | 212 | 106 | −13 | −5 | 563 |

| Nova Scotia | 0 | 52 | 173 | 267 | 303 | 196 | 37 | 1,028 |

| Total | 0 | 289 | 382 | 567 | 437 | 186 | 33 | 1,894 |

Electricity trade

The North American electricity grid is strongly interconnected, particularly in eastern regions. Historically, Canada is a net exporter of electricity to the United States, mainly due the availability of low-cost hydroelectric generating resources. In 2016, electricity trade with the United States resulted in a net export of 63.8 TWh, with net revenue of $2.7 billion. (see footnote 42)

The proposed Amendments would slightly increase imports and reduce electricity exports since a greater portion of domestic capacity would be used to supply the domestic market. Net exports to the United States would be an average of 2.8 TWh lower per year between 2030 and 2044 in the policy scenario relative to the baseline scenario. Cumulatively, exports to the United States are 39.5 TWh lower in the policy scenario than in the baseline scenario. The reduction in net export revenue would be approximately $1.4 billion. It should be noted that Canada remains a net exporter of electricity in both the baseline and policy scenarios, and the change in trade represents a small share of overall electricity demand in Canada.

Most of the reduction in electricity exports is due to the expected change in flows from Quebec. A portion of the electricity that is currently exported to New York State or New England in the baseline scenario would be sent to New Brunswick in the policy scenario. The loss in export revenue represents a welfare loss to Canadians and is attributed to New Brunswick. There would also be a loss of exports to the United States associated with a decrease in electricity generated in Nova Scotia that would have travelled to the United States through New Brunswick. The value of reduced exports attributed to Nova Scotia is approximately $181 million.

Table 6.A shows the net impact on electricity trade balances for affected provinces. This includes both import spending and lost revenue.

| 2019–2025 | 2026–2030 | 2031–2035 | 2036–2040 | 2041–2045 | 2046–2050 | 2051–2055 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alberta | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Saskatchewan | 0 | 0 | −12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | −13 |

| New Brunswick | 0 | 138 | 455 | 430 | 223 | −13 | −5 | 1,229 |

| Nova Scotia | 0 | 25 | 116 | 12 | 12 | 11 | 4 | 181 |

| Total | 0 | 186 | 516 | 479 | 242 | 0 | 0 | 1,423 |

Totals may not add up due to small impacts in provinces not directly affected by the proposed Amendments.

O&M costs

Natural gas-fired electricity generating units have lower fixed and variable O&M costs than coal-fired electricity generating units. The average undiscounted cost of fixed and variable O&M for a natural gas-fired combined cycle unit is expected to be approximately $6,210/MW, and $1.6/megawatt-hour (MWh), respectively in all provinces between 2019 and 2055. Whereas the average undiscounted costs for a coal-fired unit are $12,000/MW for fixed O&M and $2.1/MWh for variable O&M, over the same period.

The proposed Amendments would result in lower O&M costs of about $196 million. Table 6.B shows the combined fixed and variable O&M savings as a result of the proposed Amendments.

| 2019–2025 | 2026–2030 | 2031–2035 | 2036–2040 | 2041–2045 | 2046–2050 | 2051–2055 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alberta | 0 | −17 | −3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | −21 |

| Saskatchewan | 0 | −1 | −7 | −6 | −2 | 0 | 0 | −16 |

| New Brunswick | 0 | −8 | −29 | −26 | −14 | 0 | 0 | −76 |

| Nova Scotia | 0 | −7 | −29 | −22 | −15 | −9 | −3 | −85 |

| Total | 0 | −32 | −67 | −54 | −31 | −9 | −3 | −196 |

Totals may not add up due to small impacts in provinces not directly affected by the proposed Amendments.

Fuel costs

Fuel costs account for most variable generating expenses for thermal units. The proposed Amendments would result in net fuel costs totalling $667 million.

Table 6.C shows the expected incremental fuel costs of the proposed Amendments, which would total $667 million over the time frame. While fuel costs for most affected provinces would increase, New Brunswick would experience fuel savings from shutting down the coal-fired electricity generating unit in 2030 and replacing the lost generation with imports from Quebec. (see footnote 43)

| 2019–2025 | 2026–2030 | 2031–2035 | 2036–2040 | 2041–2045 | 2046–2050 | 2051–2055 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alberta | 0 | 184 | −45 | −4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 135 |

| Saskatchewan | 0 | 20 | 92 | 66 | 23 | 0 | 0 | 201 |

| New Brunswick | 0 | −96 | −198 | −193 | −103 | 0 | 0 | −590 |

| Nova Scotia | 0 | 34 | 86 | 277 | 306 | 194 | 36 | 932 |

| Total | 0 | 135 | −67 | 143 | 225 | 194 | 36 | 667 |

Totals may not sum due to small impacts in provinces not directly affected by the proposed Amendments.

Fuel prices vary by province and over time, but as shown in Table 7, the expected price paid by electric utility generators for natural gas is expected to be approximately double the cost of coal when compared in terms of cost for delivered energy, measured as dollars per million British thermal units (MMBtu).

Coal prices are forecast based on historic prices adjusted using the growth rate of the average mine mouth coal price taken from the U.S. Energy Information Administration Annual Energy Outlook 2015 reference case.

Historical natural gas prices are based on data from Statistics Canada, and future prices are forecast according to the world natural gas price from the National Energy Board's projection for the Henry Hub prices and adjusted regionally through consultation with stakeholders.

| Alberta | Saskatchewan | New Brunswick | Nova Scotia | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 | Coal | 1.45 | 2.15 | 5.54 | 3.91 |

| Natural gas | 3.50 | 4.03 | 9.01 | 7.37 | |

| 2030 | Coal | 1.64 | 2.34 | 5.72 | 4.26 |

| Natural gas | 4.23 | 4.48 | 9.18 | 7.51 | |

| 2040 | Coal | 1.82 | 2.52 | 5.90 | 4.44 |

| Natural gas | 4.58 | 4.83 | 9.53 | 7.87 | |

| 2050 | Coal | 1.82 | 2.52 | 5.90 | 4.44 |

| Natural gas | 4.58 | 4.83 | 9.53 | 7.87 | |

Welfare loss from reduced electricity use

In 2015, Canadians consumed 512.9 TWh of electricity from utility generators. (see footnote 44) In the baseline scenario, domestic demand for electricity from utility generators is expected to increase to 608.3 TWh by 2040. In the policy scenario, electricity demand in 2040 would be nearly 200 GWh lower.

Since, in most cases, compliance costs would be passed on to consumers, retail prices would be higher in the policy scenario relative to the baseline scenario. In response to higher prices, consumers would shift behaviour toward lower electricity-dependent activities or more efficient technologies. The quantified impact of the cost of reduced electricity-dependent behaviour is calculated as the change in domestic electricity consumption multiplied by the retail electricity prices in the policy scenario. This is a measure of how much consumers in the policy scenario would need to be compensated to use the same level of electricity as in the baseline scenario. In terms of welfare loss, this is similar to compensating variation. This measure may overstate the true welfare cost since it does not account for the welfare gained from the substitution toward lower electricity-dependent activities. As shown in Table 8, the value of the loss in welfare would be approximately $248 million.

| 2019–2025 | 2026–2030 | 2031–2035 | 2036–2040 | 2041–2045 | 2046–2050 | 2051–2055 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alberta | 0 | 0 | 49 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 58 |

| Saskatchewan | 0 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 18 |

| New Brunswick | 0 | 0 | 5 | 41 | 32 | 0 | 0 | 79 |

| Nova Scotia | 0 | 0 | 12 | 25 | 28 | 24 | 5 | 94 |

| Total | 0 | 0 | 66 | 87 | 66 | 24 | 5 | 248 |

Government costs

There would be negligible incremental government costs associated with the administration, compliance promotion, and enforcement of the proposed Amendments. Costs to government from the Regulations were identified in the 2012 Regulatory Impact Analysis Statement (RIAS). (see footnote 45) A minimal and reactive compliance promotion approach would be adopted by the Department within the first year after the publication of the proposed Amendments. This would include posting information on the Government of Canada website, including the amended Regulations, this RIAS, frequently asked questions, and answers to information or clarification requests.

Summary of benefits and costs

| Quantified impacts | 2019–2025 | 2026–2030 | 2031–2035 | 2036–2040 | 2041–2045 | 2046–2050 | 2051–2055 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Benefits | ||||||||

| Avoided climate change damage | 0 | 643 | 1,169 | 1,038 | 597 | 131 | 47 | 3,626 |

| Air quality improvement | 0 | 450 | 425 | 256 | 120 | 17 | 5 | 1,273 |

| Total benefits | 0 | 1,093 | 1,594 | 1,294 | 717 | 149 | 51 | 4,898 |

| Costs | ||||||||

| Capital costs | −40 | 1,660 | −587 | −220 | −525 | −86 | −116 | 85 |

| Electricity supply costs | 0 | 289 | 382 | 567 | 437 | 186 | 33 | 1,894 |

| Reduced electricity use | 0 | −12 | 66 | 87 | 66 | 24 | 5 | 237 |

| Total costs | −40 | 1,938 | −139 | 434 | −23 | 123 | −78 | 2,216 |

| Net benefits | 40 | −846 | 1,734 | 860 | 740 | 25 | 129 | 2,683 |

| Other quantified metrics | ||||||||

| Reduction in GHG emissions (Mt CO2e) | 0 | 16 | 31 | 29 | 18 | 4 | 2 | 100 |

| Reduction in NOx emissions (kt) | 0 | 37 | 73 | 56 | 34 | 5 | 1 | 206 |

| Reduction in SOx emissions (kt) | 0 | 90 | 223 | 150 | 75 | 13 | 5 | 555 |

The anticipated GHG emission reductions of 100 Mt would be achieved at an estimated cost of $22 per tonne by 2055, as shown in Table 10.

The proposed Amendments are expected to reduce GHG emissions by 16.3 Mt CO2e in 2030. To achieve these GHG emission reductions, it is expected that compliance costs of $1.9 billion would be incurred, or $116 per tonne. This cost per tonne measure is skewed by high upfront costs, while the avoided costs are accrued in the following years.

| Costs (Millions of Dollars) | GHG Emission Reductions (Mt CO2e) |

Cost per Tonne | |

|---|---|---|---|

| By 2055 | 2,216 | 100.5 | 22.06 |

| By 2030 | 1,898 | 16.3 | 116.22 |

Distributional impact analysis

The Maritimes would be most affected by the proposed Amendments, with over three quarters of the incremental costs occurring in Nova Scotia and New Brunswick. The majority of this cost would come from the increased cost to supply their customers with electricity, either through higher fuel costs or by purchasing power from another region. Table 11 shows the cost breakdown by province, as well as the share of total costs. The share of total costs is close to the share of GHG emission reductions from each province (shown in Table 1).

| Capital Cost | Supply Costs | Welfare Loss from Reduced Electricity Use | Total Cost | Share of Total Cost | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alberta | 6 | 115 | 54 | 175 | 8% |

| Saskatchewan | 61 | 172 | 13 | 246 | 11% |

| New Brunswick | −80 | 563 | 77 | 561 | 25% |

| Nova Scotia | 101 | 1,028 | 93 | 1,221 | 55% |

| Rest of Canada | −3 | 16 | 0 | 12 | 1% |

| Total | 85 | 1,894 | 237 | 2,216 | 100% |

Competitiveness impact

As discussed above, the proposed Amendments would increase generation costs. These costs could be recovered through price increases, although these would have to be approved by either the Provincial Cabinet in Saskatchewan, or by electricity regulators for New Brunswick and Nova Scotia.

Alberta is not expected to be significantly affected by the proposed federal policy since a coal phase-out is already planned for 2030 as part of the province's Climate Leadership Plan. The proposed Amendments require coal-fired units to shut down one year earlier (by December 31, 2029), but the effects are expected to be minimal in Alberta since business decisions would be largely attributable to the provincial policy.

Residential retail price impacts

The proposed Amendments could affect residential electricity consumers with a limited ability to accommodate higher electricity retail prices. As shown in Table 12, residential electricity prices could be up to 12.3% higher in affected provinces in the policy scenario compared to the baseline scenario. Based on 2016 prices, (see footnote 46) such an increase would add up to $184 and $200 to the average annual electricity bill in New Brunswick and Nova Scotia, respectively.

| Estimated Average Monthly Electricity Bill in 2016 ($) | Highest Percentage Increase in Policy Scenario Relative to Baseline Scenario (%) | Estimated Annual Increase in Electricity Spending ($) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Calgary, Alberta | 104.00 | 8.5 | 106.08 |

| Regina, Saskatchewan | 146.45 | 1.2 | 21.09 |

| Moncton, New Brunswick | 124.98 | 12.3 | 184.47 |

| Halifax, Nova Scotia | 158.83 | 10.5 | 200.13 |

There is a slightly greater proportion of older residents with lower incomes in New Brunswick and Nova Scotia than in other regions of the country. According to the 2016 Census, (see footnote 47) 17% of Canadians were older than 64 years of age in 2016. In Nova Scotia and New Brunswick, 20% of the population were over the age of 64 years. The median income reported by individuals who filed income tax returns in 2015 was $33,920 for all Canadians of all ages, (see footnote 48) whereas the median income reported by individuals in Nova Scotia was $31,580 and $30,480 in New Brunswick.

Impacts on Canada's interprovincial and international electricity trade

Canadian electricity exports are primarily from provinces with large amounts of low-cost, non-emitting electricity generation. For example, Quebec, Manitoba, and British Columbia — provinces that almost exclusively generate hydroelectricity — accounted for roughly two thirds of Canadian exports in 2016. Ontario accounted for approximately 28% of Canadian exports and has no coal-fired electricity generation. While Canadian and U.S. electricity markets are integrated to some extent, limits on transmission systems between the two countries would moderate the impacts on trade flows between the two countries.

The proposed Amendments would not impose any barriers for Canadian exports of electricity to the United States. However, the quantity of Canadian electricity surplus available to be exported could be affected. If provinces affected by the proposed federal Amendments respond to lost capacity by purchasing electricity from other provinces, this may result in fewer exports to the United States. According to the Department's modelling, the proposed Amendments would cause an average of 6% of projected Canadian electricity exports destined for the United States to be redirected to provinces that have phased out coal-fired generation capacity annually between 2030 and 2044. These changes are unlikely to affect the revenue of electricity generators in exporting provinces, which, as a result of the proposed Amendments, would only be selling electricity to different customers.

Market forces, tax incentives, U.S. state-level environmental policies and technology development would be more important determinants of electricity trade balance between Canada and the United States going forward, as these factors would dictate the long-term development of electricity generation in the United States.

Competitiveness of electricity intensive industries

Electricity price impacts induced by the proposed Amendments could reduce the competitive position of certain manufacturing and extractive industries in the four provinces that would be affected by the policy. The cost exposure of sectors would vary, but would generally be influenced by the intensity of electricity use of the firms' operations. Electricity-intensive sectors operating in these provinces include pulp, paper and paperboard mills; industrial gas manufacturing; pesticide and fertilizer manufacturing; and potash mining.

While costs for these sectors could increase as a result of electricity price increases, any impacts on the competitiveness position could be mitigated through a number of ways. For example, price increases could be passed on to consumers for firms that have sufficient market power. In addition, provincial utilities may have some discretion in the degree of electricity price increases faced by large electricity consumers. Meanwhile, electricity price impacts would be reduced for industrial facilities that generate electricity on-site, which is currently the case, for example, at some pulp and paper and potash facilities in affected provinces. For context, it should be noted that other factors have a greater influence on the competitive environment faced by industry, including labour and capital costs, proximity to market, tax treatment, exchange rates, infrastructure, and rule of law. (see footnote 49)

Labour market considerations

Three sectors could experience direct labour market impacts from proposed Amendments: coal mining; coal-fired electricity generation; and the coal transportation sector, including ports and railways.

In 2016, between 2 000 and 3 500 people were directly employed in the Canadian thermal coal mining sector, with mines located in British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan and Nova Scotia. The sector's labour force represents up to 0.02% of Canadian employment. (see footnote 50), (see footnote 51) Employment in the Canadian coal mining sector, which includes employment in both thermal coal and metallurgical coal mines, has declined since 2013, concurrent with a 12% decrease in coal production between 2013 and 2016. (see footnote 52) The prospect of increasing exports of Canadian thermal coal is weak. In 2017, Westmoreland's Coal Valley Mine was the only Canadian thermal coal mine exporting its product. (see footnote 53) European markets are shrinking and are already being supplied by countries with lower production costs, while growth markets in Asia are expected to be supplied by their own domestic production as well as cost-competitive Indonesian, Russian and Australian exports. Consequently, Canadian thermal coal exports are unlikely to increase and most Canadian thermal coal mines that supply domestic consumption are not expected to continue to operate after the proposed Amendments come into effect.