Canada Gazette, Part I, Volume 155, Number 25: Order Amending Schedules 2 and 3 to the Tobacco and Vaping Products Act (Flavours)

June 19, 2021

Statutory authority

Tobacco and Vaping Products Act

Sponsoring department

Department of Health

REGULATORY IMPACT ANALYSIS STATEMENT

(This statement is not part of the Order or the Regulations.)

Executive summary

Issues: There has been a rapid increase in youth vaping in Canada. Young persons are being exposed to vaping product-related harms, including those related to nicotine exposure, which can result in a dependence on nicotine and an increased risk of tobacco use. Health Canada has identified the availability of a variety of desirable flavours, despite the current restrictions, as one of the factors that has contributed to the rapid rise in youth vaping.

Description: The proposed Order Amending Schedules 2 and 3 to the Tobacco and Vaping Products Act (Flavours) and the proposed Standards for Vaping Products' Sensory Attributes Regulations (the proposal) would implement a complementary, three-pronged approach to restricting flavoured vaping products. First, it would further restrict the promotion of flavours in vaping products to tobacco, mint, menthol and a combination of mint and menthol (mint/menthol), including through indications or illustrations on packaging. Second, it would prohibit all sugars and sweeteners as well as most flavouring ingredients, with limited exceptions to impart tobacco and mint/menthol flavours. Third, it would prescribe sensory attributes standards to prevent a sensory perception other than one that is typical of tobacco or mint/menthol.

Rationale: Further restricting the promotion of flavours, limiting flavouring ingredients and prescribing sensory attributes standards in vaping products are expected to contribute to making these products less appealing to youth, which would help address the rapid rise in youth vaping. The proposal would leave some flavour options for adults who smoke and wish to transition, or have transitioned, to vaping, which is a less harmful source of nicotine than cigarettes if they switch completely to vaping.

The proposal would support Canada's Tobacco Strategy, which aims to reduce the burden of disease and death from tobacco use and its consequential impact on the health care system and society. The proposal is expected to primarily benefit youth by contributing to the reduction in the number of those experimenting with vaping products, who could otherwise be exposed to and become dependent on nicotine and transition into tobacco users. There would be long-term benefits in terms of avoided tobacco-related mortality and morbidity, including from exposure to second-hand smoke.

The proposal would result in total incremental costs estimated at $569.3 million expressed as present value (PV) over 30 years (or about $45.9 million in annualized value). The monetized costs to the vaping industry include the disposal of stocks of non-compliant flavoured vaping products, which could no longer be sold or distributed, potential industry profit losses and reformulation costs. Implementation of the proposal would result in incremental costs to Health Canada from performing compliance and enforcement activities.

A break-even analysis indicates that a decrease in the annual vaping initiation rate of 2.55% relative to the baseline initiation rate, assuming a 10% decrease to the annual rate at which people who smoke switch to vaping, would be sufficient to produce public health benefits equivalent to or greater than the estimated monetized costs.

The small business lens applies. There is no administrative burden on businesses that would result from the proposal; therefore, the one-for-one rule does not apply.

The proposal would not align with measures in the United States, as there are currently no restrictions on flavours in vaping products at the federal level. However, the proposal would generally align with flavour restrictions in Denmark, where characterizing flavours other than tobacco and menthol are banned. Canada would be the first jurisdiction to propose a complementary, three-pronged approach that would combine restrictions on flavour indications, ingredients and related sensory attributes. The proposed approach is expected to best help protect young Canadians from inducements to use vaping products.

Issues

There has been a rapid increase in youth vaping in Canada. Data from the 2018–2019 Canadian Student Tobacco, Alcohol and Drugs Survey (CSTADS) indicates the prevalence of vaping has doubled among students compared to the previous survey in 2016–2017. Because of this rise in the prevalence of vaping among youth, young persons are being exposed to vaping product-related harms, including those related to nicotine exposure, which can result in a dependence on nicotine and an increased risk of tobacco use. Health Canada is also concerned that the use of vaping products could renormalize smoking behaviour.

The availability of a variety of desirable flavours is believed to have contributed to the rise in youth vaping.

Background

In 2015, a Report of the House of Commons' Standing Committee on Health, “Vaping: Toward a Regulatory Framework for E-Cigarettes,” recommended adopting a new legislative framework to regulate vaping products through the Tobacco Act, new legislation or other relevant statutes. In response, the Act to amend the Tobacco Act and the Non-smokers' Health Act and to make consequential amendments to other Acts was adopted, receiving royal assent on May 23, 2018. As a result, vaping products are subject to the Tobacco and Vaping Products Act (TVPA) and either the Food and Drugs Act (FDA) or the Canada Consumer Product Safety Act (CCPSA), depending on whether the product is marketed for therapeutic use. The provisions of the TVPA apply to all vaping products, including those regulated under the FDA, except where they are expressly excluded from the application of the TVPA and some of its provisions (e.g. through the Regulations Excluding Certain Vaping Products Regulated under the Food and Drugs Act from the Application of the Tobacco and Vaping Products Act). The TVPA regulates, in addition to tobacco, the manufacture, sale, labelling and promotion of vaping products.

The overall objective of the TVPA with respect to vaping products is to prevent vaping product use from leading to the use of tobacco products by young persons and non-users of tobacco products. Specifically, it aims to

- (1) protect young persons and non-users of tobacco products from inducements to use vaping products;

- (2) protect the health of young persons and non-users of tobacco products from exposure to and dependence on nicotine that could result from the use of vaping products;

- (3) protect the health of young persons by restricting access to vaping products;

- (4) prevent the public from being deceived or misled with respect to the health hazards of using vaping products; and

- (5) enhance public awareness of those hazards.

The TVPA contains certain restrictions with regard to flavours to help protect young persons from inducements to use vaping products. Confectionery, dessert, cannabis, soft drink and energy drink are flavours listed in Schedule 3 of the TVPA, and as such, cannot be promoted in relation to vaping products, including on packaging, as per section 30.48. The TVPA provides the power to amend the list of prohibited flavours in Schedule 3 by order of the Governor in Council.

Another provision, section 30.46, prohibits the display on vaping product packages of an indication or illustration, including a brand element, that could cause a person to believe the product is flavoured if the indication or illustration could be appealing to young persons.

As per sections 7.21 and 7.22 of the TVPA, the manufacture and sale of vaping products containing ingredients listed in Schedule 2 are prohibited. Section 7.23 allows for amendments to Schedule 2. Finally, section 7.2 prohibits the manufacture and sale of a vaping product that does not conform with the standards established by regulations, while section 7.8 provides regulation-making powers to establish standards respecting the sensory attributes of vaping products and their emissions, such as odour.

Five provinces have adopted measures to regulate flavoured vaping products, to varying degrees and through different approaches (see the section entitled “Regulatory cooperation and alignment” for further details).

Canada's Tobacco Strategy

Tobacco use is the leading preventable cause of disease and premature death in Canada. It is a known or probable cause of more than 40 debilitating and often fatal diseases of the lungs, heart, and other organs, and is responsible for over 47 000 premature deaths every year in Canada. Tobacco products contain nicotine, a highly addictive substance responsible for tobacco dependence and consequent repeated long-term use that results in chronic exposure to harmful chemicals. Health and economic costs associated with tobacco use in Canada were estimated at $12.3 billion for the year 2017.footnote 1

Canada's Tobacco Strategy (CTS), introduced in 2018, features broad, population-based approaches to achieve the ambitious target of less than 5% tobacco use by 2035. Targeted approaches focus on specific populations suffering from high levels of tobacco use. One of the CTS objectives is to protect youth and non-tobacco users from nicotine addiction.

For persons who smoke, the best thing they can do to improve their health is to quit smoking. However, the CTS notes that giving adults who smoke access to less harmful options than cigarettes will help reduce their health risks and possibly save lives. There is a growing body of evidence indicating that vaping products, while not harmless, are a source of nicotine that is a less harmful alternative to smoking if a person who smokes switches completely to vaping products; this can reduce one's exposure to the many toxic and/or cancer-causing chemicals from smoking tobacco.

Health concerns and nicotine addiction

Vaping products are harmful. They emit an aerosol that contains potentially harmful chemicals. The inhalation of these chemicals into the lungs may have a negative impact on health, especially for youth and non-users of tobacco products.

Most vaping products contain nicotine. Children and youth are especially susceptible to the harmful effects of nicotine, including addiction. Youth can become dependent on nicotine at lower levels of exposure than adults do.footnote 2 Exposure to nicotine during adolescence can also negatively alter brain development, including long-term effects on memory and concentration abilities.footnote 3,footnote 4,footnote 5

Public Health Consequences of E-Cigarettes, published in 2018 by the U.S. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, represents expert consensus resulting from an independent, systematic review of a high volume of peer-reviewed scientific studies.footnote 6 The report offers three conclusions that are of particular significance in supporting the need to further protect youth and non-users of tobacco products:

- (1) there is substantial evidence that the use of an e-cigarette results in symptoms of dependence;

- (2) there is conclusive evidence that in addition to nicotine, most e-cigarette products contain and emit numerous potentially toxic substances; and

- (3) there is substantial evidence that e-cigarette use increases the risk of ever using combustible tobacco cigarettes among youth and young adults.

Youth vaping

Data from the 2018–2019 CSTADS indicates the prevalence (past 30 days) of vaping doubled among students compared to the previous survey in 2016–2017.footnote 7 Twenty percent of students (418 000 individuals) in grades 7 to 12 (Secondary I through V in Quebec) had used an e-cigarettefootnote 8 in the past 30 days, double the 10% from 2016–2017. In 2018–2019, the past-30-day prevalence was 11% (115 000) among students in grades 7 to 9 (Secondary I to III in Quebec) and 29% (304 000) among students in grades 10 to 12 (Secondary IV and V in Quebec). Further data is presented in Figure 1. Data indicates that frequency of use is high, particularly in the upper grades: the prevalence of daily or almost daily e-cigarette use was 13% (133 000) among students in grades 10 to 12. As a comparison, the prevalence of daily cigarette use among students in grades 10 to 12 was 1% (14 000) in 2018–2019.

Figure 1: Past-30-day e-cigarette use grouped by grade (CSTADS)

Figure 1 - Text version

| Year | Prevalence of past-30-day use of e-cigarettes by students in grades 7 to 9 (CSTADS) |

|---|---|

| 2014–2015 | 3.2% |

| 2016–2017 | 5.4% |

| 2018–2019 | 11.1% |

| Year | Prevalence of past-30-day use of e-cigarettes by students in grades 10 to 12 (CSTADS) |

|---|---|

| 2014–2015 | 8.9% |

| 2016–2017 | 14.6% |

| 2018–2019 | 29.4% |

Vaping rates among youth (15 to 19 years old) remain high. Data from the 2019 and 2020 Canadian Tobacco and Nicotine Survey (CTNS) suggests the rapid increase in youth vaping, observed between 2017 and 2019, may be levelling off, as there was no statistical difference between the 2019 and 2020 past-30-day prevalence rate (15% vs. 14%).footnote 9 It remains to be seen whether this survey results, while being encouraging, would translate into a downward trend in the prevalence of youth vaping in the future. This would only be possible by collecting and analyzing survey results over several cycles.

The availability of a variety of desirable flavours in vaping products is not the only factor believed to have contributed to the rise in youth vaping. Other key factors include an increase in promotional activities relating to vaping products, including on social media, the introduction of high-nicotine-concentration vaping products and innovative design features.

Addressing the rise in youth vaping

Health Canada is taking action to address the rise of youth vaping. These actions are expected to protect young persons and non-users of tobacco products from inducements to use vaping products. The Department is concerned that young persons are being exposed to harms related to vaping products, including those related to nicotine exposure, which can result in a dependence on nicotine and an increased risk of tobacco use and adverse health effects. Canada's public health achievements in tobacco control risk being eroded if young persons who experiment with vaping develop a dependence on nicotine, particularly those who would not otherwise have tried smoking.

Health Canada has invested more than $13 million in a national, targeted, youth-oriented public information campaign, Consider the Consequences of Vaping, to increase youth awareness of the harms of vaping. The campaign, launched in early 2019, comprises several components:

- Advertising: It is estimated digital advertisements had been seen more than 840 million times as of October 2020. An evaluation of the advertising campaign found that 26% of teens who reported having seen the advertisements decided not to vape as a result.

- Experiential events: As of December 2020, experiential event tours in schools and community venues across the country had engaged 90 683 students in person and 1 694 students virtually.

- Distribution of resources: Since January 2019, over 40 000 web-based and print resources have been distributed to youth, parents and educators. From April 2019 to March 2021, over 595 000 visits to the campaign page have been registered.

- Influencers: In 2019 and 2020, digital influencers who targeted parents and youth were very effective in amplifying campaign messages through a variety of social media content.

Health Canada is also working with other levels of government, the medical community and other stakeholders to address multi-jurisdictional issues and enhance national cooperative and collaborative efforts to protect young persons and non-users of tobacco products from the health hazards of vaping. Grants of $12.4 million have been allocated over six years to address tobacco use and youth vaping through the Substance Use and Addictions Program. In particular, non-governmental and academic partners are using the funds to focus on youth vaping cessation projects or projects that have youth vaping cessation components. For example, a project with the University of Toronto ($1.3 million) will significantly enhance existing app-based approaches to support vaping cessation among youth and young adults. Meanwhile, the University of Waterloo ($1.1 million) is expanding its survey capacity — including the use of biomarkers — to better understand youth vaping behaviour patterns and measure their risk exposure.

In addition, Health Canada has taken action to help address the rise in youth vaping through the Vaping Products Labelling and Packaging Regulations (VPLPR), the Vaping Products Promotion Regulations (VPPR) and the proposed Nicotine Concentration in Vaping Products Regulations (NCVPR).

The VPLPR, made in December 2019, establish two sets of requirements: Part 1 sets out labelling requirements pursuant to the TVPA, while Part 2 sets out labelling requirements and child-resistant container requirements pursuant to the CCPSA.

Part 1 requires the display of two labelling elements for vaping products that contain nicotine: a nicotine concentration statement and a health warning on the addictiveness of nicotine. This labelling must be displayed on the vaping products and/or their packaging. Part 1 also sets out three permitted expressions that may be used on the product or its packaging when a vaping substancefootnote 10 does not contain nicotine and, in the case of any other vaping product that contains a vaping substance, when the product is without nicotine. This is to enhance the awareness of the health hazards of using vaping products and to prevent the public from being deceived or misled with respect to the health hazards posed by their use.

Part 2:

- requires a list of ingredients for all vaping substances on product labels;

- prohibits vaping products with nicotine concentrations of 66 mg/mL or more;

- requires warnings on the toxicity of nicotine when ingested (including a first-aid treatment statement); and

- requires refillable vaping products, including devices and their parts that contain nicotine, to be child-resistant.

The objective of this part is to protect the health and safety of young children by reducing the risk that they ingest vaping substances containing toxic concentrations of nicotine. The nicotine concentration limit was set at 66 mg/mL or more to address the risks associated with acute poisoning if nicotine in these products is ingested.

The VPPR, made in June 2020, set out measures to further restrict the promotion of vaping products to youth. Subject to limited exceptions, the VPPR prohibit the promotion of vaping products and vaping product-related brand elements through advertising that could be seen or heard by young persons. The VPPR also prohibit the display of vaping products and vaping product-related brand elements at points-of-sale where the product, or brand elements, may be seen by young persons. This includes online points-of-sale. These measures help protect youth from inducements to using vaping products.

The VPPR also require vaping product advertising conveys a warning about the health hazards of using vaping products. This is subject to certain exceptions, including for advertising at a point of sale that indicates only the availability and price of vaping products. The VPPR also set out the conditions for how the health warning and the attribution to Health Canada are presented in both audio and visual vaping advertisements. The objective of the health warnings on permitted advertising is to enhance public awareness about the health hazards of using vaping products.

The proposed NCVPR, prepublished in December 2020, would limit nicotine concentration in vaping substances to 20 mg/mL. They would also amend the VPLPR to ensure alignment between both sets of regulations for vaping products manufactured or imported for sale in Canada.

Use of flavoured vaping products

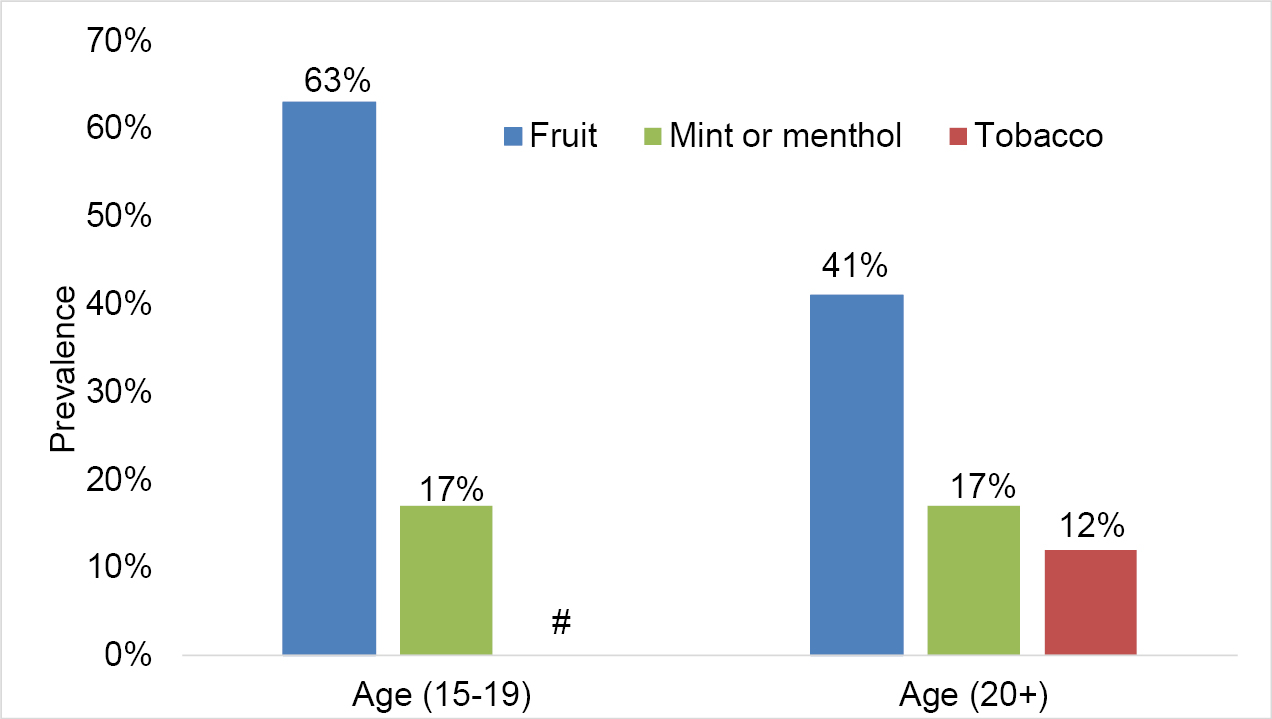

Data from the 2020 CTNS indicates that the use of some flavour categories differs by age groups. Fruit flavours were consistently used the most often among all who reported past-30-day vaping. Adults aged 20 and above reported mint/menthol flavour (17%) as the next flavour most used, followed by tobacco (12%) [see Figure 2].footnote 11

Figure 2: Flavour categories most often used among past-30-day vapers, by age group (CTNS, 2020)

Figure 2 - Text version

| Flavour | Percentage of past-30-day use of most often used flavoured vaping products by youth aged 15 to 19 |

|---|---|

| Fruit | 63% |

| Mint or menthol | 17% |

| Tobacco | No data Note: High sampling variability; although an estimate may be determined from the data, data should be supressed. |

| Flavour | Percentage of past-30-day use of most often used flavoured vaping products by adults aged 20 and over |

|---|---|

| Fruit | 41% |

| Mint or menthol | 17% |

| Tobacco | 12% |

# High sampling variability; although an estimate may be determined from the table, data should be suppressed.

A review of the literature dating from late 2016 to early 2018 cites several studies showing flavour uses vary with age groups and smoking status. Young people, especially those who do not smoke, were more likely to initiate vaping with fruit and sweet flavours, compared with young adults who overall preferred sweet, menthol, and cherry flavours. Adults also preferred sweet flavours, and disliked bitter or harsh flavours. The same research indicates adults who smoke, especially men, liked tobacco flavour the most, followed by menthol and fruit flavours.footnote 12 Another extensive review of recent literature published in 2019 also found the majority of youth and young adults who vape use non-tobacco-flavoured e-cigarettes, while older adults and people who smoke may use flavoured e-cigarettes at lower rates than youth and people who do not smoke.footnote 13

Unflavoured vaping products are not popular: over 99% of vaping products sold in Canada are flavoured.footnote 14

Reasons for using vaping products

Flavours are an important reason for vaping among young people and among adults. In a 2018 public opinion survey that investigated reasons for using vaping products, those who said they vaped because of the flavours were predominantly younger:

- Vapers aged 15–19 years (51%);

- Vapers aged 20–24 years (54%); and

- Vapers aged 25+ years (30%).footnote 15

In a separate study, the presence of flavour was also a top reason mentioned by youth for vaping. Data from the 2019 Wave 3 International Tobacco Control Youth Tobacco and Vaping Survey indicates that, of youth in Canada aged 16–19 who had vaped in the past 30 days, 40% reported they use vaping products “for the flavour” among their top five reasons. The other four reasons included “for fun/I like it” (50%), “curiosity/to try something new” (39%), “for the nicotine” (24%) and “to deal with stress or anxiety” (35%).footnote 16

The 2018 public opinion survey commissioned by Health Canada showed adults aged 25 and above who vape were also more likely to smoke or be former smokers using vaping products to quit smoking or reduce the number of cigarettes smoked. In contrast, youth and young adults took more of a recreational approach to vaping and were more likely to see it as appealing in its own right; they were more likely to vape because of the flavours, and reported greater switching between flavours.footnote 17

Role of flavour indications, ingredients and sensory attributes in inducing youth to vape

Flavour is the complex combination of taste, smell and trigeminalfootnote 18 sensations in the mouth, throat and nasal cavity. Sensory stimulation before and during use influence the sensory experience. A growing body of research suggests that all of our senses play a role in influencing flavour perception.footnote 19,footnote 20 For example, the experience of eating food will usually involve not just its taste and smell, but also its colour, weight, shape, firmness, crunchiness, juiciness and even the sound of chewing and perhaps its provenance.

The literature in food consumer science shows flavours influence the appeal of food products, and that flavour preferences drive food selection. Certain flavours are particularly attractive to youth; for example, youth have a heightened preference for sweet food tastes and greater rejection of bitter food tastes.

Flavoured vaping products are widely appealing to youth. Flavours influence both product perceptions and usage behaviours among youth. Flavours other than tobacco, as well as the presence of sugars and sweeteners, are associated with increased product appeal, decreased perception of harm and increased intention to try or use by users and non-users (i.e. people who have never tried vaping or tobacco products before).footnote 21,footnote 22,footnote 23,footnote 24,footnote 25

Among youth, non-tobacco-flavoured vaping products are perceived as less harmful than tobacco-flavoured vaping products. Adolescents in the United States and the United Kingdom perceive flavoured vaping products (including fruit, candy, and menthol flavours) as less harmful to health than tobacco-flavoured vaping products.footnote 26,footnote 27,footnote 28,footnote 29

Sugars and sweeteners in vaping products further increase youth appeal. Studies suggest preferences for sweet flavours in e-cigarettes are likely due to increases in perceived smoothness and sweetness as well as reductions in perceived bitterness or harshness, which is most likely from the presence of nicotine.footnote 30,footnote 31 A recent study found that, in addition to appeal, sweet tastes increase the reinforcing effects of nicotine in e-cigarettes, resulting in heightened brain cue-reactivity in adults. The researchers concluded that sweeteners may increase the abuse liability of e-cigarettes.footnote 32

Flavouring ingredients can make the taste, smell, and general sensory experience of inhaling the aerosolized vaping substances very pleasant. Laboratory research has shown that flavouring ingredients are present in vaping products. Health Canada recently tested over 800 vaping liquids to characterize their chemical constituents, including flavouring ingredients.footnote 33 Preliminary analyses show the presence of at least 630 flavouring chemicals across 18 different flavour categories, with many of them present in different flavour categories. The most frequently used flavouring ingredients were vanillin (present in 39% of all vaping liquids tested), ethyl maltol (31%) and ethyl vanillin (28%). Vanillin is described as “sweet, powerful, creamy, and vanilla-like.” Ethyl maltol is known to be “sweet, fruity-caramellic, cotton candy.” Ethyl vanillin is portrayed as bringing “intense, sweet, creamy, vanilla-like” notes.footnote 34

In addition to flavouring ingredients, sugars (e.g. sucrose, glucose and fructose) have been detected in flavoured vaping liquids.footnote 35 Some sweeteners other than sugars (e.g. sucralose and aspartame) have been marketed for use in vaping liquidsfootnote 36 and actual use has been reported.footnote 37

Flavour indications play an important role in product appeal. Studies report significant effects of odour names on perception of pleasantness, intensity and arousal.footnote 38 Flavours may be promoted, through indications (names and descriptors) and illustrations, in such a manner as to increase youth awareness, curiosity and openness to try vaping.footnote 39

New flavour names, often quite creative, are constantly coming onto the market. Research on the global evolution of online choices (proxy for the market as a whole) from 2014 to 2017 shows unique flavour options doubled from 7 764 to 15 586.footnote 40,footnote 41 Estimates from 2019 Canadian market data are in the range of 3 000 unique flavour indications.footnote 42 These flavours are promoted with names that can be classified in a number of categories. Examples include the following:

- Fruit, such as mango, crazy strawberry, cucumber, melon time, citrus fizz, passionate pear and fruit punch;

- Spices, such as cinnamon kiss, ginger bliss, bourbon vanilla and vanilla sin;

- Tobacco, such as Virginia tobacco, toasted tobacco and golden tobacco;

- Mint/menthol, such as cool mint, polar mint, frost bite and creamy menthol;

- Nuts, such as peanut butter and nut job;

- Beverages, such as alcoholic beverages (brandy, pina colada and citrus gin) and non-alcoholic ones (cool tea, chai and double double coffee);

- Combination names, such as banana vanilla, watermelon ice and apple tobacco;

- Suggestive names, such as honeymoon, brain freeze, orchard and tropical; and

- Neutral names that do not indicate or suggest a specific flavour, such as Loch Ness and matata.

Role of flavours in facilitating switching from cigarette smoking to vaping

Health Canada notes that no vaping products have been approved as smoking cessation aids. To seek such an authorization, manufacturers would have to make a therapeutic claim for their vaping product, such as smoking cessation aid, and present substantive scientific evidence of efficacy, safety and quality in support of their application.

Health Canada is aware of self-reported information from people who vape indicating the important role flavours played in helping them transition away from smoking, and in continuing to help them maintain abstinence from smoking.footnote 43

Measures to limit flavours in vaping products to reduce their appeal to youth may also make these products less attractive to people who either vape as an alternative to cigarettes or to stay abstinent from smoking. Adults who successfully quit smoking with vaping products often cite flavours as important in breaking the link with smoking.footnote 44 Fruit flavours are the preferred choice for adults and youth. However, adults are much more likely than youth to also identify tobacco as a preferred or usual flavour.footnote 11,footnote 45 A recent study conducted in both Canada and the United States shows that a variety of non-tobacco flavours, especially fruit, are popular among adults who vape, particularly among those who have quit smoking and are now exclusively vaping.footnote 46

Results of another study that surveyed participants in Australia, Canada, England and the United States indicate that people who vape, and use “sweet flavours” (which included 11 different flavour groups, namely fruit, candy, and desserts), were more likely to transition away from cigarette smoking and quit cigarette use, at least in the short term, compared to those who used tobacco-flavoured or unflavoured vaping products.footnote 47 At this time, it is unknown what the impact would be on people who vape if they had no access to their preferred vaping product flavour.

Objective

The objective of the proposal is to protect young persons from inducements to use vaping products by further restricting flavour indications, limiting flavouring ingredients and prescribing sensory attributes standards. Overall, this is expected to contribute to reducing the appeal of vaping products to youth.

The proposal, in association with other vaping-related measures under the TVPA, aims to prevent vaping product use from leading to nicotine addiction and to the use of tobacco products by young persons. The proposal would maintain access to certain flavours in vaping products for adults who cannot quit smoking and who seek an alternative source of nicotine that, without being harmless, is less harmful than cigarettes.

Description

The proposal would consist of the proposed Order Amending Schedules 2 and 3 to the Tobacco and Vaping Products Act (Flavours) and the proposed Standards for Vaping Products' Sensory Attributes Regulations. The proposal would restrict the manufacture, promotion, and furnishing (including retail sale) of flavoured vaping products in Canada. The proposal would not apply to suppliers of flavouring ingredients nor would it apply to the export of flavoured vaping products.

More specifically, the proposal would involve three components:

- Further restricting the promotion of flavours.

The proposal would amend Schedule 3 to the TVPA to expand the list of flavours whose promotion is prohibited. Promotion includes any indication such as the name or descriptor, or illustration, including a brand element, on the packaging or elsewhere.footnote 48 The only flavours that could be promoted would be that of tobacco and that of mint, menthol or a combination of mint and menthol (hereafter referred to as mint/menthol). Promotions for a tobacco flavour could include a reference to a type of tobacco (e.g. “Virginia tobacco”), but not to a type of tobacco product (e.g. pipe tobacco). Reference to a type of mint (e.g. “peppermint”) would be allowed on vaping product packaging, but not to a type of product made with mint (e.g. “mint mojito”). The use of any descriptors or illustrations on vaping product packaging would have to also comply with the current restrictions on promotion under the TVPA.

- Prohibiting most flavouring ingredients, and all sugars and sweeteners in vaping products.

The proposal would amend Schedule 2 to the TVPA, resulting in a ban on most flavouring ingredients and on all sugars and sweeteners from use in the manufacture of vaping products, unless these products are for export or authorized under the FDA. The ban would apply to ingredients that have flavouring properties or that enhance flavour. Ingredients can be identified as having such properties by consulting different sources, including the documents incorporated by reference in the proposal.footnote 49 A list of 40 excluded ingredientsfootnote 50 that could be used to impart a tobacco flavour, and a separate list of 42 that could be used to impart a mint/menthol flavour, would be set out in the Schedule.footnote 51

To determine which flavouring ingredients to exclude, Health Canada first chemically analyzed samples of vaping liquids to identify the flavouring chemicals present. Then, relative frequencies of detection of each flavouring chemical were calculated in samples represented as tobacco flavoured, and those represented as mint/menthol flavoured, relative to other flavoured samples. Finally, flavouring chemicals were further screened for their ability to impart either a tobacco or a mint/menthol flavour, as well as for their occurrence in tobacco or mint plants, as reported in the literature.footnote 52

The proposal would also exclude six basic ingredients of vaping liquids (nicotine, glycerol, propylene glycol, benzoic acid, citric acid and sorbic acid) whose use would otherwise be prohibited given their flavouring properties.footnote 53 Therefore, they could be used in either unflavoured or flavoured vaping products.

The prohibition on the use of sugars and sweeteners would align with existing bans on their use in tobacco products and cannabis.

- Prescribing sensory attributes standards.

The proposal would set out a standard mandating that a vaping product — manufactured using the specified excluded ingredients that would be listed in Schedule 2 — or its emissions not have sensory attributes that result in a sensory perception other than one that is typical of tobacco or mint/menthol. In this case, sensory perceptions refer to perception derived from stimuli to olfactory (smell), gustatory (taste) or trigeminal chemosensoryfootnote 54 systems.

These three components are intended to complement each other. The prohibition on most flavouring ingredients and on all sugars and sweeteners would limit the manufacturers' ability to make vaping products that have a highly pleasant smell or taste (e.g. through the use of ingredients like vanillin and ethyl maltol) or to use ingredients that add a flavour note other than tobacco or mint/menthol. There would be no restrictions over which of the excluded flavouring ingredients could be used by a manufacturer to create a flavour and in which proportions. Therefore, the sensory attributes standards would help limit users' perceptual experience to one that is typical of tobacco or mint/menthol. Finally, the promotional restrictions would help align the promotion of the products' flavours with the products' contents and the users' perceptions.

Drugs and devices authorized under the FDA

The proposal would exempt all drugs and devices subject to an authorization under the FDA from the proposed restrictions on ingredients and on the promotion of flavours, instead of only prescription drugs as is currently the case. This would include drugs and devices containing a controlled substance as defined under the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act subject to an authorization under the FDA. This would mean that vaping products that have not met the requirements of the FDA and are not authorized as a drug or device under that regime would be subject to all proposed restrictions.

Coming into force

The proposal would come into force on the 180th day after the day on which the regulations and order are registered.

Regulatory development

Consultation

Reducing youth access and the appeal of vaping products: Consultation and potential regulatory measures

The consultation document entitled Reducing Youth Access and Appeal of Vaping Products: Potential Regulatory Measures was published on the Government of Canada's website on April 11, 2019, providing a 45-day comment period that closed on May 25, 2019. Canadians were invited to submit comments on a number of potential regulatory measures that could be considered to further reduce the access and the appeal of vaping products to youth. One of the measures proposed was to prohibit the manufacture and sale of vaping products with certain flavours or flavour ingredients and/or prohibiting the promotion of certain flavours.

Over 24 000 submissions were received in response to this consultation, including 288 unique responses from a variety of stakeholders, 100 template submissions from health professionals, health organizations and the general public, nearly 23 000 postcards and almost 1 450 template emails from people who vape.footnote 55

The consultation asked Canadians whether flavour categories for which promotion is prohibited (Schedule 3 to the TVPA) should be expanded and/or whether the manufacture and sale of vaping products with certain flavours or flavouring ingredients (Schedule 2 to the TVPA) should be prohibited. This issue garnered the most responses in the consultation. Excluding postcard responses, 66% were supportive of further restrictions, 20% were unclear or did not state a position and 14% were opposed. Few respondents differentiated between prohibiting the manufacture and sale of certain flavours or flavouring ingredients and prohibiting the promotion of certain flavours.

A summary of the comments received is available on the Government of Canada website.

Suggestions for regulatory measures included

- Prohibiting the manufacture and sale of flavours appealing to youth (candy, dessert and fruit) while still permitting a range of flavoured products for adults who smoke;

- Restricting the promotion of product names to the flavour and not descriptive terms that evoke feelings or sensations (i.e. mint vs. cool mint, apple vs. sour apple, etc.);

- Prohibiting the promotion of unidentifiable flavours (i.e. unicorn milk, dragon's blood); and

- Creating a list of approved ingredients as opposed to a list of prohibited ingredients.

Other suggestions relating to flavours intersected with issues of youth access, nicotine concentration, design, and regulatory openness and transparency. These included

- Restricting the sale of flavoured products to adult-only specialty shops and online or to behind the counter (prescription only) in pharmacies;

- Prohibiting or restricting the manufacture and sale of flavoured products with high levels of nicotine; and

- Restricting the availability of vaping product flavours to only those that are currently available in nicotine replacement therapy, such as nicotine-containing nasal sprays, inhalers, gum and lozenges.

Almost 23 000 postcards were received from people across Canada who reported using vaping products to quit smoking. A specialty vape shop owner from Ontario self-identified as the campaign organizer. None of the postcard submissions supported further flavour restrictions and a caption at the bottom of the postcards read: “Flavours helped me stop smoking.” As for flavour preference, approximately 52% reported a preference for fruits, 18% for candy and dessert, 15% for flavours categorized by Health Canada as “other,” 9% for mint and menthol, 6% for tobacco and less than 1% for flavourless products. Many respondents listed two or more flavours, and some respondents emphasized their dislike for tobacco-flavoured vaping liquids.

Many respondents perceived vaping products as bad as or worse than cigarettes, and saw no downside to increased regulation on flavours. Some respondents reported that young people understand “less harmful” than cigarettes to mean safe. Of the parents and educators who provided a clear opinion, most were in favour of additional flavour restrictions. These included prohibiting all flavour promotions, prohibiting the manufacture and sale of all or certain flavoured products and restrictions on the concentration of flavour chemicals.

Some submissions were from people with family members and friends who had quit smoking with flavoured vaping products after having tried many other methods. These respondents felt further restrictions would be damaging to the success of vaping products as a viable alternative to cigarettes. Some people who vape reported that flavours helped them quit smoking and help them maintain abstinence from tobacco. Many people shared that their sense of taste returned and that vaping helped them realize how unpleasant the taste of tobacco was.

Others felt people who are serious about quitting smoking could do so without flavours, or with a limited number that are less appealing to youth. These respondents were of the opinion that the benefit of prohibiting flavours that appeal to youth outweighs the risk that some adults who smoke may not switch. Many respondents indicated that the evidence supporting the effectiveness of vaping products for smoking cessation is mixed or poor, and that people who smoke should rely on proven quit methods.

Academics' opinions were divided between those who saw benefit in further restrictions, those who had no specific feedback on flavours, and those who felt further restrictions would be detrimental to helping adults switch from smoking to vaping.

Respondents representing industry and, more generally, convenience retailers and convenience retailer associations were also generally opposed to further restrictions on flavours. Some emphasized the small window of time that had passed between the TVPA restrictions on flavour promotions coming into effect (November 2018) and the time of the consultation. They suggested Health Canada assess the impacts of these initial restrictions before imposing more.

Many owners of vape shops suggested Health Canada's focus should be on restricting access to flavours, and not restricting the flavours themselves. These respondents voiced concerns regarding potential downsides of more regulation, including Canadians turning to an illegal market for flavoured products, adults returning to smoking and financial hardship on the Canadian vaping industry. A submission by an industry association noted that thousands of flavours have been available in Canada for over a decade, but it has only been since the recent introduction of closed pod-based systems (which have relatively few flavour offerings), and their accompanying mass marketing campaigns, that youth uptake has become a problem.

Some industry respondents expressed worry about the financial burden that would be created by increased promotional restrictions and accompanying relabelling requirements. A number of respondents argued restricting any specific flavour ingredient not based on a documented hazard would be arbitrary and unjustified.

A strong theme emerging from the consultation, and shared among many different categories of stakeholders, was the need for increased enforcement of the current provisions of the TVPA that explicitly prohibit the promotion of flavours appealing to youth, as well as the promotion and sale of products with design features that appeal to young people.

Consultation as part of the prepublication in the Canada Gazette, Part I, of the NCVPR

Consultation on the proposed NCVPR was open from December 19, 2020, to March 4, 2021, providing a 75-day comment period. As part of the consultation, Health Canada received 87 comments pertaining to restricting flavours in vaping products. These comprised 63 unique comments; 3 comments from a Rights for Vapers email campaign; 13 from a Canadian Vaping Association email campaign and 8 from a public health authority email campaign. Of those 87 comments, 60 opposed any restrictions on flavours, 13 supported a ban on all flavours, 10 supported a ban on all flavours with the exception of tobacco and 1 a ban on all flavours except tobacco, mint and menthol. Three comments were unclear.

Health Canada's response to key stakeholder concerns

Prohibiting all flavours with the exception of tobacco

Several stakeholders suggested banning all flavours with the exception of tobacco.

Response: Flavours other than tobacco are associated with decreased harm perception and increased appeal among youth. However, not all flavours are equally appealing to youth and evidence shows that fruit flavour is the most popular. By prohibiting all flavours with the exception of tobacco and mint/menthol, Health Canada aims to strike a balance between reducing the appeal of vaping products, to protect youth from inducements to use vaping products, and leaving some flavour options for adults who smoke and who have transitioned, or wish to transition, to vaping.

Location of sale of flavoured vaping products

Some stakeholders suggested that Health Canada limit the sale of flavoured vaping products, other than tobacco, to age-restricted specialty vape shops.

Response: Restrictions on the retail sale of vaping products fall under provincial jurisdiction. The proposal does not preclude provinces limiting where vaping products can be sold. Ontario and British Columbia currently have restrictions to that effect.

Illicit market

Some stakeholders, including some members of the industry, said further flavour restrictions would lead to an increase in black-market sales of vaping products with prohibited flavours.

Response: Health Canada recognizes that an illicit vaping products market could be a concern. However, the proposal leaves room for the continued availability of some flavour options that should help deter people from procuring non-compliant vaping products (illicit market). The Government of Canada will continue to monitor market trends and take appropriate actions where necessary.

Adults who used to smoke returning to smoking

Some respondents opined that any further restriction in flavours would lead to people reverting from vaping back to smoking.

Response: The proposal aims to reduce the appeal to youth of vaping products. However, a few flavour options would remain available for adults who smoke and wish to transition, or have transitioned to vaping.

In addition, there are many options for Canadians who vape and do not wish to return to smoking. A convenient way to access information and services for help is to contact the pan-Canadian toll-free quit line. Trained specialists answer questions and provide advice, tips and referrals to programs and services in people's communities. Information on how to access nicotine replacement therapy and other medications that can help with the potential withdrawal symptoms is also available.

Provincial and territorial governments provide most services, products and medications, as well as counselling, as part of their programs. The Government of Canada provides access to similar products and medications to eligible First Nations and Inuit through the Non-Insured Health Benefits Program. In addition, Health Canada maintains a website with a variety of resources to provide advice on quitting smoking, such as the On the Road to Quitting self-help guide.

Enforcing current restrictions

Some stakeholders stated that instead of introducing new restrictions on flavours, Health Canada should focus its efforts on the enforcement of the existing provisions of the TVPA prohibiting the promotion of youth-friendly flavours, as well as the promotion and sale of products with design features that appeal to young people.

Response: Health Canada has actively monitored compliance with the TVPA and will continue to do so to the extent possible. Between June and December 2019, Health Canada inspectors visited more than 3 000 specialty vape shops and gas and convenience (G&C) stores across the country and seized more than 80 000 units of non-compliant vaping products. Of the specialty vape shops inspected, more than 80% were found to be selling and promoting products in violation of the TVPA and/or the CCPSA. The two most common types of violation observed were the promotion of vaping product flavours appealing to young persons and the promotion of vaping products through testimonials or endorsements. During the COVID-19 pandemic, Health Canada focused its inspection resources on the online activities of regulated parties, and on conducting vaping product package/label assessments. Despite those efforts, youth vaping continues to be a pressing problem that needs to be addressed on many fronts. The proposal is intended to strengthen the existing restrictions and give Health Canada an additional tool to help protect youth from inducements to use vaping products.

Modern treaty obligations and Indigenous engagement and consultation

The proposal is not expected to impact modern treaties with the Indigenous peoples of Canada. Analysis regarding possible differential impacts on Indigenous peoples is set out in the “Gender-based analysis plus (GBA+)” section below.

Instrument choice

Option 1: Baseline scenario (no further restriction on flavoured vaping products)

In the baseline option, there would be no further federal restrictions on vaping product flavours. This option would consist of continuing to enforce the existing legislative regime with respect to the promotion of flavours set out in sections 30.46 and 30.48 of the TVPA. Section 30.48, in particular, prohibits the promotion and sale of a vaping product where there are reasonable grounds to believe any description or illustration on the packaging refers to a specific flavour descriptor listed in Schedule 3 (e.g. confectionery, soft drink flavours). Existing TVPA restrictions would continue to apply. Health Canada would continue to enforce the TVPA through existing compliance and enforcement activities. Fruit-flavoured and other flavoured vaping products that are appealing to youth would therefore remain in the market.

Youth living in provinces and territories that do not have additional measures in place to restrict flavours or to limit access to flavoured products would not be protected from inducement to use vaping products caused by the availability of a variety of desirable flavours.

Therefore, the status quo is not considered an appropriate option.

Option 2: Further restrict the promotion of flavoured vaping products by adding fruit flavours to the existing list of prohibited flavours in Schedule 3

This option would add fruit to the list of prohibited flavours in Schedule 3 to the TVPA, resulting in a ban on the promotion and sale of vaping products whose packaging show any indication or illustration of fruit.

This option would not restrict the actual flavouring ingredients used to manufacture vaping products. Therefore, manufacturers could continue to market products that would taste and smell like fruit, a flavour that is popular with youth. Furthermore, manufacturers could continue to promote flavours using creative and enticing flavour indications, other than fruit, that could appeal to youth (e.g. vanilla sin or cinnamon kiss).

This option would not sufficiently help protect youth from inducements to use vaping products; it was therefore rejected.

Option 3: Further restrict the promotion of all flavours other than tobacco in vaping products by amending Schedule 3

With this option, the promotion of any flavour other than tobacco, including on the packaging, would be prohibited through an amendment to Schedule 3. This option would limit the manufacturers' ability to use creative flavour indications and illustrations that could increase youth curiosity and openness to try these flavoured vaping products.

This option is supported by recent survey data that shows vaping products with a tobacco flavour are not commonly used by young persons. At the same time, as this option would not restrict the actual flavouring ingredients used to manufacture vaping liquids, manufacturers could continue to market products that would taste and smell like fruit, a flavour that is popular with youth, even if not promoted as such.

On a different note, this option would not permit the promotion of mint/menthol-flavoured vaping products. Leaving some flavour options, such as mint and menthol, for adults who smoke and who have transitioned, or wish to transition, to vaping would help strike a balance with reducing the appeal of vaping products to protect youth from inducements to use vaping products. This option would to some degree help protect youth from inducements to use vaping products, but would not help strike a balance between this goal and that of leaving some flavour options for adults who smoke and who have transitioned, or wish to transition, to vaping; it was therefore not considered appropriate.

Option 4: Further restrict the promotion of all flavours other than tobacco or mint/menthol by amending Schedule 3, and prescribe standards on sensory attributes such that vaping products only bring to the user smell, taste and chemesthetic sensations typical of tobacco or mint/menthol

This option would restrict the promotion of flavours, including on the packaging, to only tobacco and mint/menthol. It would limit the manufacturers' ability to use creative flavour indications and illustrations that could increase youth curiosity and openness to trying these flavoured vaping products.

By prescribing sensory attributes standards, this option would also limit manufacturers' ability to impact users' experience by requiring that vaping products provide a sensory perception typical of tobacco or mint/menthol. This is roughly similar to the “characterizing flavours” approach adopted by a few jurisdictions; Denmark, for example, prohibits all vaping products with a characterizing flavour other than tobacco or menthol.

As this option would not restrict the actual flavouring ingredients used to manufacture vaping liquids, manufacturers could continue to market vaping products that, while meeting the sensory attributes standards, would make use of ingredients such as vanillin and ethyl maltol to impart sweet notes to the permitted tobacco and mint/menthol flavours. In addition, this option would not prevent the continued use of sugars (e.g. sucrose) and sweeteners (e.g. sucralose) in vaping products. These sugars contribute to increased perceptions of smoothness and sweetness as well as decreased perceptions of bitterness or harshness; research has shown that young people are attracted to “sweet flavours.”

This option would help strike a balance between leaving some flavour options for adults who smoke and who have transitioned, or wish to transition, to vaping, and protecting youth from inducements to use vaping products. However, it would not prevent the marketing of tobacco- or mint/menthol-flavoured vaping products with sweet notes or containing sugars and sweeteners, which would appeal to youth. This option was therefore rejected.

Option 5: Recommended — Only allow tobacco or mint/menthol flavours in vaping products using a three-pronged approach: (1) further restricting the promotion of flavours listed in Schedule 3; (2) adding in Schedule 2 flavouring ingredients, with exceptions, and sugars and sweeteners as prohibited ingredients, and; (3) prescribing sensory attributes standards

This option would expand on option 4 with matching restrictions on vaping products formulation: the use of most flavouring ingredients and of all sugars and sweeteners would be prohibited. Consequently, vaping products with a tobacco flavour could only be made with a limited number of flavouring ingredients, without sugars or sweeteners, and only promoted as having a tobacco flavour, including on the packaging. In addition, flavouring ingredients used in the manufacture of tobacco-flavoured vaping products would be required to result in a sensory perception typical of tobacco. The same restrictions would apply to mint/menthol-flavoured vaping products.

This option would also provide clarity to regulated parties by identifying the sole flavouring ingredients one could use to impart the promoted flavours.

This option would leave on the market some flavour option other than tobacco for the benefit of adults who smoke and who have transitioned, or wish to transition, to vaping. However, with the other flavour options such as fruit eliminated, mint/menthol-flavoured vaping products may start attracting more young people, although likely to a lesser degree given the absence of “sweet notes,” sugars and sweeteners in these products; if this were to take place, it would likely diminish this option's effect on protecting youth from inducements to use vaping products.

This option is recommended because it provides youth with a high degree of protection from inducements to use vaping products, while providing some flavour options for adults who smoke and who have transitioned, or wish to transition, to vaping. The Department will continue efforts to help people who smoke quit and remain smoke free.

Regulatory analysis

Benefits and costs

Summary of cost-benefit analysis

The proposal is expected to contribute to reducing the appeal of flavoured vaping products to youth. It would protect young persons from inducements to use vaping products. It would do so by further restricting the promotion of flavours in vaping products to tobacco and mint/menthol, including through indications or illustrations on packaging, limiting the ingredients that can be used and prescribing sensory attributes standards.

The proposal would result in total incremental costs estimated at $569.3 million expressed as present value (PV) over 30 years (or about $45.9 million in annualized value). The monetized costs to the vaping industry include the disposal of stocks of non-compliant flavoured vaping products, which could no longer be sold or distributed, potential industry profit losses and reformulation costs. Implementation of the proposal would result in incremental costs to Health Canada from performing compliance and enforcement activities.

The proposal would support the CTS, which aims to reduce the burden of disease and death caused by tobacco use and its consequential impact on the public health care system and on society. The proposal is expected to primarily benefit youth by contributing to the reduction in the number of those who experiment with vaping products, which can lead to exposure to and dependence on nicotine and increased risk of tobacco use. Long-term economic benefits would be realized in terms of avoided tobacco-related mortality and morbidity, including exposure to second-hand smoke. The break-even analysis indicates that a decrease in the rate of vaping initiation of 2.55% relative to the baseline initiation rate, assuming a 10% decrease in the annual rate at which people who smoke switch to vaping, would be sufficient to produce public health benefits equivalent to or greater than the estimated monetized costs.

Analytical approach

The Cabinet Directive on Regulation requires departments to analyze the costs and benefits of federal regulations. To measure these impacts, the benefits and costs are estimated by comparing the incremental change from the current regulatory framework (i.e. the baseline scenario) to what is anticipated to occur under the new regulatory approach (i.e. the regulatory scenario). The proposal is expected to come into effect in 2022. This cost-benefit analysis (CBA) covers the 30-year period from 2022 to 2051. A 7% discount rate is used to estimate the present value of the incremental costs and incremental benefits. All values reported for the 30-year period are expressed in 2019 constant dollars.

The impacts of the proposal have been estimated using three approaches: quantitative analysis, where possible; qualitative analysis; and break-even analysis. The costs analysis incorporates information gathered through interviews of representatives of the vaping industry. A summary of the CBA is provided herein. A copy of the CBA report is available upon request from hc.pregs.sc@canada.ca.

Overview of the vaping products market

The overall vaping products market in Canada was estimated at $1.36 billion in 2019. There are approximately 200 vaping liquid manufacturers in Canada and 15–20 large distributors. Canadian importers of vaping liquids and devices obtain their supplies (devices and raw materials / ingredients, including nicotine and flavouring preparations) mostly from the United States and China. Between 85% and 95% of the total volume of vaping liquid sold in Canada is manufactured in Canada. The 50 largest manufacturers account for about 80% of this share. Vaping liquid sold in bottles is almost exclusively manufactured in Canada, while vaping liquid sold in pre-filled pods is almost exclusively imported into Canada. Bottled liquid outsold pod liquid by a factor of at least 7 to 1 in terms of volume in 2019. Contract manufacturing of vaping substances (i.e. vape shops using the services of a laboratory to manufacture their vaping liquids) is common in Canada.footnote 56,footnote 57,footnote 58

Vaping products are sold in three main categories of stores: vape shops, G&C stores and online retailers. The market breakdown by channel based on value is as follows: 49% in vape stores, 30% in G&C stores, 21% online. There are 1 400 vape stores, 25% of which are chain retailers, as well as 27 240 G&C stores, 37% of which are chain retailers, and about 1 500 websites, most of which are the online retail component of brick-and-mortar stores.footnote 59,footnote 42 The majority of these businesses, including manufacturers, are considered to be small under the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat definition.footnote 60

Overview of the number of vaping products in Canada

Considering both bottled and pods-contained vaping liquids, the CBA estimates a total of 1 070 to 11 400 stock keeping units (SKUs) currently on the market, with the majority in the vaping liquid refills category. This estimate is reasonably consistent with Euromonitor International's estimate of about 3 000 or more flavoured vaping liquid products available in Canada. While this range is quite large, it reflects the lack of systematic data on the vaping liquid market.

Overview of vaping product users in Canada

Data from the 2020 CTNS shows the prevalence of past-30-day vaping was 13% among young adults aged 20 to 24, and 3% among adults aged 25 and older. Furthermore, never smokers made up the majority of past-30-day vape users within youth aged 15 to 19 (74%). This contrasts with young adults aged 20 to 24 and adults aged 25 and older, where the majority of past-30-day vapers were either current or former smokers, at 46% and 94%, respectively.footnote 11

Assessment of costs and benefits

It is anticipated that the proposal would impact youth, adults who smoke or vape and the vaping industry in all provinces and territories, except for Nova Scotia (NS) and Prince Edward Island (PEI), which already have regulations in place to ban the sale of flavoured e-cigarettes and liquids with the exception of tobacco flavour (in force April 2020 and March 2021, respectively). Ontario and British Columbia have enacted a variety of other regulations that affect the channels through which flavoured vaping products can be sold.footnote 61 Finally, federal regulations made under the TVPA, such as the VPPR and the proposed NCVPR, could modify the size and nature of the vaping products market, directly affecting the baseline for this cost analysis. It is difficult to forecast how the sum effect of the federal and provincial measures will impact the vaping products market.

Baseline and regulatory scenario

Under the baseline scenario, flavoured vaping products would continue to be sold in provinces and territories where no restrictions on flavoured vaping products exist. Therefore, fruit-flavoured and other flavoured vaping products that are appealing to youth would remain in the market. Certain flavours (confectionery, dessert, cannabis, soft drink, energy drink) cannot be promoted, including on the packaging. Youth living in provinces and territories that do not have additional measures in place to restrict flavours or to limit access to flavoured products would continue to be subject to inducements to use vaping products.

Under the regulatory scenario, the promotion, manufacturing and sale of all flavoured vaping products, with the exception of tobacco and mint/menthol flavours, would be prohibited. Specifically, vaping products would have to be compliant with the proposed further restrictions on flavour indications, prohibition of most flavouring ingredients and sensory attributes standards (which would result in sensory properties typical of tobacco or mint/menthol flavours). The proposal would implement a complementary, three-pronged approach, expected to help protect young persons from inducements to use vaping products.

Quantitative costs

General assumptions

The following general assumptions were made in the CBA:

- Market shares in NS and PEI are estimated at 3% and 0.4% respectively.footnote 62 The proposal would have minimal impact on store inventories in these provinces where a prohibition on all flavours other than tobacco in vaping products is already in effect. However, there would be some tobacco-flavoured vaping products in NS and PEI that may be impacted by the prohibition of most flavouring ingredients in vaping products and would have to be reformulated.

- As the NCVPR would come into force before this proposal, some of the cost impacts to industry may be overstated. For example, this analysis does not take into consideration the adults who will stop vaping because of the decrease in nicotine concentration mandated by the NCVPR but rather considers them as adults who may quit vaping because of the restrictions on flavours.

- It is anticipated that the following stakeholders will be affected by the proposal: manufacturers (200), importers (20), vape shops (1 358), G&C stores (26 509), youth, adults who smoke, as well as Health Canada.

- Only the sales to adult consumers are considered in the analysis. It was estimated that adults represent approximately 83% of the Canadian vaping product market.footnote 63,footnote 64

- The growth rate of the vaping product market is zero.footnote 65

- Publication of the proposal in Canada Gazette, Part II, is assumed to be in 2022, with an implementation period of 6 months. All impacts are discounted to 2022. The analytical period is from 2022 to 2051.

1. Costs to vaping liquid manufacturers associated with the prohibition of most flavouring ingredients — disposal of non-compliant products

The proposal would restrict flavouring ingredients allowed in vaping products on the market.

Affected manufacturers and importers are expected to gather and dispose of non-compliant products already distributed to retailers. It is also assumed the retailers would return non-compliant products to the manufacturers and importers. It is expected those manufacturers and importers would bear the one-time costs associated with the disposal of non-compliant products. To estimate the costs associated with disposing of non-compliant products, the analysis first estimates the quantity of non-compliant products that would be left on store shelves after the transition period of six months. The analysis assumes the proposal would have no impact on store inventories in NS and PEI, where a prohibition on flavours other than tobacco is already in effect. The analysis then estimates the marginal cost per unit of non-compliant products by removing retail profit and manufacturer profit from the average retail price reported by Euromonitor International.footnote 42

The resulting estimate of manufacturing cost (marginal cost) per bottle is roughly $13.footnote 66 The estimated costs were calculated by multiplying the unit price with total quantities of non-compliant products, plus the cost of disposing of stocks of non-compliant products (multiplying the tonnage of non-compliant refills with disposal cost per tonne). The one-time incremental cost associated with the disposal of non-compliant vaping products is estimated at $72.2 million PV over 30 years (or about $5.8 million in annualized value). This cost would be borne in 2022.

2. Costs to vaping industry associated with the prohibition of most flavouring ingredients — profit loss

Restrictions on the availability of vaping liquids in flavours other than tobacco or mint/menthol would reduce the appeal of vaping products to those who prefer other flavours. It is anticipated manufacturers, importers and all retail channels would carry potential profit loss due to the loss in sales.

2.1. Profit loss to manufacturers and importers

It is anticipated manufacturers and importers would bear profit losses as a result of a projected decline in consumer demand for vaping products. Available evidence on how restrictions on flavours might affect consumer demand for vaping products was examined. Based on this evidence, an estimated reduction in consumer demand was used to determine the effect on profits for vaping product manufacturers and importers.

The following key assumptions were used in estimating these costs:

- Manufacturers' gross profit margins range from 25% to 51% (a midpoint value of 38% was used for the CBA results), with the upper bound based on responses to a survey conducted by Health Canada in the context of the regulatory development of the proposed NCVPR. In the lower bound, the analysis roughly halved the estimated profit to better reflect margins earned by smaller manufacturers of bottled liquids.footnote 67

- The estimated reduction in consumer demand for vaping products ranged from 10% to 14.3%.footnote 68 The consumer demand reduction rate of 12.15% (midpoint of the range) was used in the analysis and presented in cost results.

- Annual profits are assessed for the 30-year period (2022–2051). However, due to a 6-month implementation period, profit losses to manufacturers and importers in the first year reflect only 6 months of lost profits. The ongoing 12-month profit loss is assumed for 2023 to 2051.

The analysis estimated the reduction in consumer demand for vaping products based on the impacts of NS's recently implemented restrictions on flavours. The analysis was based on data for weekly sales of pods in the Maritime provinces, i.e. NS, New Brunswick, and PEI.

The NS case and review of the literature provide useful insights into the potential effect of flavour restrictions on consumer demand for vaping products. NS experienced a 14.3% reduction in pod sales following implementation of its “tobacco flavour-only” requirement (mint/menthol-flavoured vaping products are prohibited in NS). Hence, it is expected the decline in consumer demand for vaping products as a result of this proposal would be lower than in NS, i.e. at 10%. In light of the greater likelihood that industry would stop producing some tobacco, and mint/menthol variants, it was concluded that using the reduction in consumer demand for vaping products in NS could be better suited for the upper bound estimate. Thus, this analysis assumes there would be a 10% to 14.3% reduction in consumer demand for vaping products and used a 12.15% reduction to estimate impacts.

The potential profit loss for manufacturers and importers is estimated to be $262.4 million PV over 30 years (or about $21.1 million in annualized value). This was calculated using applicable sales revenue, assuming a profit margin of 38% and a 12.15% reduction in demand for vaping products.

2.2. Profit loss to retailers

The reduction in consumer demand for vaping products could also impact profits retailers earn on the sales of e-liquids (refills and pods). Key assumptions include the following:

- The Euromonitor International study is used to associate e-liquids revenue with three retail channels: G&C stores, vape shops and other retailers (including both online retailers and specialty stores such as tobacconists).footnote 42

- Total annual profits on retail sales of vaping products are based on an assumed gross profit margin of 21.4%, reflecting overall profit earned by G&C stores in 2018, as reported by Statistics Canada.footnote 69

- Annual profits are assessed for the 30-year period (2022–2051). However due to a 6-month implementation period, profit losses to retailers in the first year reflect only 6 months of lost profits. The ongoing 12-month profit loss is assumed for 2023 to 2051.

The potential profit loss for all retailers is estimated at $199.0 million PV over 30 years (or about $16.0 million in annualized value). This was calculated by taking relevant sales revenue and assuming a profit margin of 21.4% and a 12.15 % reduction in demand.

In total, the incremental costs in terms of potential profit losses are estimated at $461.3 million PV over 30 years (or about $37.2 million in annualized value) for manufacturers, importers and retailers in the vaping industry.

3. Costs to manufacturers and importers associated with the prohibition of most flavouring ingredients — reformulation costs

The proposal would prohibit the use of sugars and sweeteners and restrict the use of most flavours in vaping products. Only 40 flavouring ingredients would be allowed in tobacco-flavoured vaping liquids, and 42 in mint/menthol-flavoured ones.

Based on a preliminary scan of a representative sample of e-liquids, Health Canada assessed the extent to which reformulation may be required. It was found that approximately 20% of tobacco-flavoured vaping products and 15% of mint/menthol-flavoured products would not require reformulation. The remaining tobacco- and mint/menthol-flavoured products (about 80% to 85%) may require reformulation and impose related costs on industry. Thus, this analysis assumes that 82.5% of tobacco- and mint/menthol-flavoured vaping products remaining on the market would be reformulated.

Manufacturers and importers may need to reformulate their tobacco or mint/menthol products by removing sugars and sweeteners as well as flavouring ingredients unless those ingredients are listed as excluded from the prohibition (see footnote 51). The proposed restrictions on ingredients may impact manufacturers and importers across Canada that would then carry incremental reformulation costs. The key assumptions include the followingfootnote 70:

- 100% of domestic manufacturers would remain in the market to continue producing tobacco- and mint/menthol-flavoured vaping products that would be in compliance with the proposed restrictions on ingredients.footnote 71 However, Health Canada acknowledges that some manufacturers and importers may choose to stop producing those products after reviewing the lists of excluded flavouring ingredients. Those businesses would suffer associated profit loss as a result.

- 100% of importers would remain in the tobacco- and mint/menthol-flavour market and would reformulate their vaping products to be in compliance with the proposed restrictions on ingredients.footnote 71

- Manufacturers and importers each produce two to four tobacco- and mint/menthol-flavoured vaping liquid variants.footnote 72 The midpoint value of three variants per manufacturer/importer is used in the analysis.

- Approximately 82.5% of variants would require reformulation per manufacturer/importer.

- The cost of reformulating one variant will range from $25,000 to $70,000 for smaller domestic manufacturers, and from $50,000 to $100,000 for larger importers of closed systems to reflect the more formalized administrative and testing procedures characteristic of larger firms.footnote 71

The reformulation cost was calculated using the number of manufacturers and importers remaining in the market after the proposal would come into force and multiplying it by the number of variants (tobacco and mint/menthol) requiring reformulation per manufacturer and per importer, and then multiplying by the reformulation cost per variant.

The reformulation cost estimate is subject to several uncertainties. These uncertainties include the share of products that would need to be reformulated, the share of manufacturers and importers remaining in the Canadian market, and the cost of reformulation per variant. The reformulation cost is estimated in the range with lower and upper bounds. The midpoint value of two bounds was used in the cost results. The one-time incremental cost associated with the reformulation of tobacco- and mint/menthol-flavoured products remaining in the market across Canada is estimated at $29.3 million PV over 30 years (or about $2.4 million in annualized value). This cost would be carried in 2022.

Government costs — Health Canada

4. Implementation, compliance and enforcement costs