Vol. 147, No. 23 — November 6, 2013

Registration

SOR/2013-187 October 25, 2013

CANADIAN ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION ACT, 1999

Regulations Amending the Renewable Fuels Regulations, 2013

P.C. 2013-1108 October 24, 2013

Whereas, pursuant to subsection 332(1) (see footnote a) of the Canadian Environmental Protection Act, 1999 (see footnote b), the Minister of the Environment published in the Canada Gazette, Part I, on May 18, 2013, a copy of proposed Regulations Amending the Renewable Fuels Regulations, 2013 and persons were given an opportunity to file comments with respect to the proposed Regulations or to file a notice of objection requesting that a board of review be established and stating the reasons for the objection;

Whereas the Governor in Council is of the opinion that the Renewable Fuels Regulations (see footnote c), as amended by the proposed Regulations, could make a significant contribution to the prevention of, or reduction in, air pollution;

And whereas, pursuant to subsection 140(4) of that Act, before recommending the proposed Regulations, the Minister of the Environment offered to consult with the provincial governments and the members of the National Advisory Committee who are representatives of Aboriginal governments;

Therefore, His Excellency the Governor General in Council, on the recommendation of the Minister of the Environment, pursuant to sections 140 (see footnote d) and 326 of the Canadian Environmental Protection Act, 1999 (see footnote e), makes the annexed Regulations Amending the Renewable Fuels Regulations, 2013.

REGULATIONS AMENDING THE RENEWABLE FUELS REGULATIONS, 2013

AMENDMENTS

1. (1) The definitions “auditor” and “distillate compliance period” in subsection 1(1) of the Renewable Fuels Regulations (see footnote 1) are replaced by the following:

“auditor”

« vérificateur »

“auditor”, in respect of a participant or a producer or importer of renewable fuel, means an individual or a firm that

- (a) is independent of the participant, producer or importer, as the case may be; and

- (b) is certified, for the purposes of carrying out International Organization for Standardization quality assurance (ISO 14000 or 9000 series) assessments, by the International Register of Certificated Auditors or by any other nationally or internationally recognized accreditation organization.

“distillate compliance period”

« période de conformité visant le distillat »

“distillate compliance period” means

- (a) the period that begins on July 1, 2011 and that ends on December 31, 2012;

- (b) the period that begins on January 1, 2013 and that ends on December 31, 2014; and

- (c) after December 31, 2014, each calendar year.

(2) Paragraph (b) of the definition “finished gasoline” in subsection 1(1) of the Regulations is replaced by the following:

- (b) has an antiknock index of at least 86, as determined by the applicable test method listed in the National Standard of Canada standard CAN/CGSB-3.5-2011, Automotive Gasoline.

(3) The portion of paragraph (b) of the definition “gasoline” before subparagraph (i) in subsection 1(1) of the Regulations is replaced by the following:

- (b) suitable for use in a spark-ignition engine and has the following characteristics, as determined by the applicable test method listed in the National Standard of Canada standard CAN/CGSB-3.5-2011, Automotive Gasoline:

2. (1) The portion of subsection 6(4) of the Regulations before paragraph (a) is replaced by the following:

Excluded volumes

(4) Despite subsections (1) and (2), a primary supplier may, before carrying forward any compliance units under section 21 or 22, subtract from their gasoline pool or distillate pool, as the case may be, the volume of a batch, or of a portion of the batch, of fuel in their pool if they make, before the end of the trading period in respect of the compliance period, a record that establishes that the volume was a volume of one of the following types of fuel:

(2) Subsection 6(4) of the Regulations is amended by adding the following after paragraph (f):

- (f.1) diesel fuel or heating distillate oil, as the case may be, sold for or delivered for use for space heating purposes;

(3) Paragraph 6(4)(h) of the French version of the Regulations is replaced by following:

- h) jusqu’au 31 décembre 2012 inclusivement, carburant diesel ou mazout de chauffage vendu ou livré pour usage en Nouvelle-Écosse, au Nouveau-Brunswick, à l’Île-du-Prince-Édouard et dans la partie de la province de Québec située au soixantième degré de latitude nord ou au sud de celle-ci;

(4) Subsection 6(4) of the Regulations is amended by adding the following after paragraph (h):

- (h.1) during the period that begins on January 1, 2013 and that ends on June 30, 2013, diesel fuel or heating distillate oil, as the case may be, sold for or delivered for use in Nova Scotia, New Brunswick and Prince Edward Island;

3. The description of DtGDD in subsection 8(2) of the Regulations is replaced by the following:

- DtGDD is the volume, expressed in litres, that is equal to

- (a) for distillate compliance periods other than the first and second ones, the value that they assigned for DtGDG in subsection (1) for the gasoline compliance period that is the same period as the distillate compliance period,

- (b) for the first distillate compliance period, the total of the values that they assigned for DtGDG in subsection (1) for gasoline compliance periods that overlapped with the first distillate compliance period, and

- (c) for the second distillate compliance period, the total of the values that they assigned for DtGDG in subsection (1) for gasoline compliance periods that overlapped with the second distillate compliance period.

4. Section 11 of the Regulations is amended by adding the following after subsection (3):

Becoming a primary supplier

(4) Despite subsection (3), when an elective participant becomes a primary supplier

- (a) they cease to be an elective participant; and

- (b) they retain their compliance units.

5. Section 19 of the Regulations is amended by adding the following after subsection (3):

Subsection 6(4) read out

(4) For the purpose of the determination referred to in subsection (1) or (2), section 6 is to be read without reference to its subsection (4).

6. Subsection 27(2) of the English version of the Regulations is replaced by the following:

Paper report or notice

(2) If the Minister has not specified an electronic form and format or if it is impractical to send the report or notice electronically in accordance with subsection (1) because of circumstances beyond the control of the person sending the report or notice, they must send it on paper, signed by an authorized official, in the form and format specified by the Minister. However, if no form and format have been so specified, the report or notice may be in any form and format.

7. Subsections 28(2) and (3) of the Regulations are replaced by the following:

Conduct of audit

(1.1) The audit must be conducted by an individual who is an auditor, or who is a member of a firm that is an auditor, and who has demonstrated the knowledge and skills required to conduct the assessments referred to in subsection (1) and in items 3 to 7 of Schedule 3.

Auditor’s reports

(2) The participant, the producer or the importer must obtain from the auditor a report in respect of the audit that contains the information set out in Schedule 3. They must, on or before June 30 following the end of the compliance period, send the auditor’s report to the Minister.

Signature

(2.1) The auditor’s report must be signed

- (a) by the auditor, if the auditor is an individual; or

- (b) by a duly authorized representative of the firm, if the auditor is a firm.

Signature — alternative

(2.2) Despite paragraph (2.1)(a), if an individual auditor referred to in that paragraph is a member of a firm, a duly authorized representative of the firm may sign the auditor’s report instead of the individual auditor.

Non-application — no compliance units created

(3) Subsections (1) to (2.2) do not apply, in respect of a compliance period,

- (a) to a producer or importer of a renewable fuel who demonstrates, in supporting documents sent together with a report referred to in subsection 34(4), that no compliance units were created from renewable fuel that they produced or imported during the compliance period; or

- (b) to an elective participant who demonstrates, in supporting documents sent together with a report referred to in section 33, that

- (i) under subsection 11(3), they ended their participation in the trading system as of a specified date referred to in that subsection that occurred during the trading period in respect of the compliance period and, during that trading period, they did not transfer any compliance units, or

- (ii) during that trading period, they neither created nor traded compliance units.

8. Section 30 of the Regulations is replaced by the following:

Annual report

30. For each compliance period during which a primary supplier produces or imports gasoline, diesel fuel or heating distillate oil, they must, on or before April 30 following the end of the compliance period, send a report to the Minister that contains the information set out in Schedule 4 for the compliance period.

9. Subsection 31(3) of the Regulations is replaced by the following:

When record made

(3) The record must be made within 30 days after the end of the month for which the information is required to be recorded.

10. Subsection 32(7) of the Regulations is replaced by the following:

Record — section 19

(7) Within 30 days after the end of each month during a compliance period, a primary supplier must make a record of the number calculated in accordance with subsection 19(1) or (2), as the case may be, for that month.

11. Section 33 of the Regulations is replaced by the following:

Annual report

33. For each compliance period in respect of which a compliance unit is created, carried forward, carried back, transferred in trade, received in trade or cancelled by a participant, the participant must, on or before April 30 following the end of the compliance period, send a report to the Minister that contains the information set out in Schedule 5 for the compliance period.

12. Section 37 of the Regulations is replaced by the following:

When records made

37. Except as otherwise provided in these Regulations, records must be made as soon as feasible but no later than 30 days after the information to be recorded becomes available.

13. Section 39 of the Regulations is replaced by the following:

December 15, 2010 to December 31, 2011

39. (1) A person who would, if the first gasoline compliance period were to end on December 31, 2011, be required to send a report under section 30 or 33 or subsection 34(4) or 36(2) must send an interim report to the Minister for the period that begins on December 15, 2010 and that ends on December 31, 2011 in accordance with that section or subsection but as if that period were the first gasoline compliance period.

January 1, 2013 to December 31, 2013

(2) A person who would, if the second distillate compliance period were to end on December 31, 2013, be required to send a report under section 30 or 33 must send an interim report to the Minister for the period that begins on January 1, 2013 and that ends on December 31, 2013 in accordance with that section but as if that distillate compliance period ended on December 31, 2013.

14. Schedule 3 to the Regulations is amended by replacing the section reference after the heading “SCHEDULE 3” with the following:

(Subsections 28(1.1) and (2))

COMING INTO FORCE

15. These Regulations come into force on the day on which they are registered.

REGULATORY IMPACT ANALYSIS STATEMENT

(This statement is not part of the Regulations.)

1. Executive summary

Issue: The requirement of 2% renewable content in heating distillate oil under the Renewable Fuels Regulations could impact Canadian families that heat their homes using heating distillate oil, since the renewable content is currently more expensive. Furthermore, the temporary exemption for Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and Prince Edward Island from the 2% renewable content requirement in diesel fuel and heating distillate oil would require primary suppliers for these Maritime provinces to have complied with the current regulatory requirements by January 1, 2013 — a date that some primary suppliers expressed was difficult to meet.

Description: The Regulations Amending the Renewable Fuels Regulations, 2013 (the Amendments) include a permanent nationwide exemption from the 2% renewable content requirement for heating distillate oil for space heating purposes (mostly home heating), as well as a six-month extension to the exemption for Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and Prince Edward Island from the 2% renewable content requirement in both diesel fuel and heating distillate oil, ending June 30, 2013.

Cost-benefit statement: Fuel suppliers are expected to respond to the Amendments by replacing some renewable fuel content with less costly diesel fuel. This is expected to result in savings (avoided fuel costs) for industry and consumers, and some social costs due to foregone reductions in greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. For the period 2013–2035, the present value of total benefits is estimated at $306 million from direct fuel cost savings for industry ($257 million) and consumers ($49 million). The present value of total costs is estimated at $53 million, based on 2.0 megatonnes (Mt) in total foregone GHG emissions reductions (averaging less than 0.1 Mt annually). The present value of net benefits is estimated at $253 million, with total benefits outweighing total costs by a ratio of almost six to one.

“One-for-One” Rule and small business lens: Environment Canada has reviewed the administrative burden estimated to result from the Amendments and has concluded that the “One-for-One” Rule does not apply, as there is no expected net change in administrative costs to businesses.

Similarly, Environment Canada has reviewed the impact of the Amendments on small businesses and concluded that the small business lens does not apply, as no costs to small businesses are expected.

2. Background

The Renewable Fuels Regulations published in the Canada Gazette, Part II, on September 1, 2010, (see footnote 2) included provisions requiring an average 2% renewable content in diesel fuel and heating distillate oil. The Regulations Amending the Renewable Fuels Regulations published in the Canada Gazette, Part II, on July 20, 2011, (see footnote 3) specified the coming-into-force date of July 1, 2011, for the 2% renewable content requirement in diesel fuel and heating distillate oil, including a permanent exemption from the requirements for Newfoundland and Labrador, the Northwest Territories, the Yukon, Nunavut, and that part of Quebec that is north of latitude 60°N and a temporary exemption from the requirements for Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island (the Maritime provinces) and that part of Quebec that is on or south of latitude 60°N on or before December 31, 2012.

The intent to propose new regulatory amendments was announced on December 31, 2012. The announcement outlined the following: a permanent national exemption for the 2% renewable content requirement for home heating oil, as well as a six-month extension to the exemption for the Maritime provinces from the 2% renewable content requirement in both diesel fuel and heating distillate oil.

3. Issue

The requirement of 2% renewable content in heating distillate oil under the Renewable Fuels Regulations could impact Canadian families that heat their homes using heating distillate oil, since the renewable content is currently more expensive. Families in the Atlantic region of Canada are more heavily reliant on heating oil to heat their homes; in 2011, sales of heating distillate oil in the Atlantic provinces (see footnote 4) were 723 litres per person, compared to 53 litres per person for the remaining Canadian provinces. (see footnote 5) Since domestic biodiesel production capacity in Atlantic Canada is low compared to potential demand, primary suppliers of distillate to this region of Canada will likely rely on more expensive imports of hydrogenation-derived renewable diesel (HDRD) to meet their obligations under the Renewable Fuels Regulations. (see footnote 6)

Furthermore, the existing expiration date for the exemption for the Maritime provinces from the 2% renewable content requirement in both diesel fuel and heating distillate oil in the current Regulations will require primary suppliers of distillates to the Maritime provinces to have complied with the full regulatory requirements by January 1, 2013 — a date that some primary suppliers expressed was difficult to meet.

4. Objectives

The exemption from the regulatory requirement of the 2% renewable content for heating distillate oil is intended to mitigate cost increases for Canadians that use oil to heat their homes. The six-month extension to the exemption for the Maritime provinces from the 2% renewable content requirement in both diesel fuel and heating distillate oil will give regulatees supplying distillates to the Maritime provinces extra time to comply with the regulatory requirements.

5. Description

The Amendments include amending section 6 of the Regulations to allow primary suppliers to subtract from their distillate pool diesel fuel or heating distillate oil sold for or delivered for use for space heating purposes (which covers over 80% of total heating distillate oil, including all home heating oil). (see footnote 7)

Section 6 is also amended to allow primary suppliers to subtract from their distillate pool all diesel fuel or heating distillate oil sold for or delivered for use in the Maritime provinces during the period from January 1, 2013, to June 30, 2013.

In order to allow suppliers more time to adjust to these changes in compliance requirements, the Amendments include an extension to the compliance period beginning on January 1, 2013, increasing it from one to two years, to end on December 31, 2014.

Also included in the Amendments is an interim report covering the period from January 1, 2013, to December 31, 2013, for distillate volumes and distillate compliance units, a 15-day extension to certain record-keeping and reporting requirements, an update to a reference standard and some other minor administrative amendments.

Additional administrative changes in the Amendments include an update to the definition of the auditor and clarifications regarding the audit report and audit report signatory requirements. The Amendments also include provisions regarding the circumstance of an elective participant becoming a primary supplier.

6. Regulatory and non-regulatory options considered

Status quo

The exemption for diesel fuel or heating distillate oil sold for or delivered for use in the Maritime provinces ended on December 31, 2012. The status quo would not provide primary suppliers of distillates to the Maritime provinces more time and flexibility to meet the required distillate blending requirements. In addition, the current Regulations do not have provisions to allow primary suppliers to subtract volumes of diesel fuel or heating distillate oil sold for or delivered for use for space heating purposes from their distillate pool, as targeted by the proposal.

Amendments

There is no mechanism under the Canadian Environmental Protection Act, 1999 (CEPA 1999) to implement, through nonregulatory means, the proposed changes to these Regulations. Therefore, the Amendments are the only option available to achieve the stated policy objectives.

7. Benefits and costs

An analysis of the benefits and costs of the Amendments was conducted to estimate the incremental impacts on key stakeholders, including the Canadian public, industry, and government. Under this analysis, fuel suppliers are expected to respond to the Amendments by replacing some renewable fuel content with less costly diesel fuel. This will result in some savings (avoided fuel costs) for both industry and consumers, and an increase in costs due to foregone reductions in greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. The Canadian government is not expected to incur any additional costs as a result of these Amendments since there will be no practical changes to administration or enforcement.

For the period 2013–2035, the incremental impacts of the Amendments have been quantified, monetized, and discounted to present value (in 2013). The present value of total benefits is estimated at $306 million from direct fuel cost savings for industry ($257 million) and consumers ($49 million). The present value of total costs is estimated at $53 million, based on 2.0 megatonnes (Mt) in total foregone GHG emissions reductions (averaging less than 0.1 Mt annually). The present value of net benefits is estimated at $253 million over 23 years, with benefits outweighing costs by a ratio of almost six to one.

7.1. Overall cost-benefit analysis (CBA) approach

This analysis of benefits and costs follows the Treasury Board Secretariat CBA guidelines (www.tbs-sct.gc.ca/rtrap-parfa/analys/analystb-eng.asp), including the following key elements:

- Current analysis: The analysis adopts a 2013 perspective in terms of using recent information about the compliance behaviour of key stakeholders to the current Regulations, and projected future economic trends.

- Incremental impacts: The Amendments are evaluated as a “regulatory” scenario in terms of their relative impacts compared to a baseline “business as usual” (BAU) scenario.

- Time frame for analysis: The time horizon used for evaluating the incremental impacts of the Amendments is 23 years and covers the period from January 1, 2013, to December 31, 2035, based on available modelling tools and consistent with other regulatory analyses.

- Quantification and monetization: The analysis attempts to identify all significant incremental impacts as costs or benefits, estimate them in quantitative terms, and monetize them in 2012 Canadian dollars. Whenever quantification or monetization was not possible, impacts have been presented qualitatively.

- Discount rate: The Treasury Board Secretariat’s 3% social discount rate was used to calculate the present value of costs and benefits, consistent with other GHG regulatory analyses.

7.2. Current analysis and key assumptions

Recent information has indicated that compliance behaviour has been and is expected to be different than previously expected in the Regulatory Impact Analysis Statement (RIAS) for the Regulations Amending the Renewable Fuels Regulations published in the Canada Gazette, Part II, on July 20, 2011. Furthermore, the current Amendments are expected to almost exclusively impact renewable content obligations for primary suppliers of distillate to Eastern Canada (see footnote 8) since nearly all heating distillate oil volumes for space heating purposes nationally are used in Eastern Canada (99% in 2012). (see footnote 9) The analysis in the current RIAS is therefore specific to volumes of distillate in Eastern Canada and the renewable fuel landscape and information available for this specific region. As a result, the estimates from this cost-benefit analysis are not directly comparable to the original analysis of the 2% renewable content requirement in diesel fuel and heating distillate oil.

Renewable content blending by primary suppliers has been reported for the first compliance period of the 2% renewable content requirement in diesel fuel and heating distillate oil (July 1, 2011, to December 31, 2012). As well, suppliers of diesel fuel and heating distillate oil to Quebec and the Maritimes, where volumes have been exempted until December 31, 2012, have stated a preference toward blending hydrogenation-derived renewable diesel (HDRD) into diesel fuel to meet their obligations under the Renewable Fuels Regulations. (see footnote 10) This information, as well as consultation with industry and government experts, has informed this analysis of the expected impacts of these Amendments.

Renewable content blended into diesel fuel

Primary suppliers may blend renewable content into heating distillate oil or diesel fuel under the Regulations, but have indicated a preference to blend almost exclusively into diesel fuel. (see footnote 11) Consistent with this finding, the RIAS assumes primary suppliers would have blended renewable content into diesel fuel. This implies that these Amendments will result in the use of more diesel fuel and less renewable content.

Renewable content composition

Both biodiesel and HDRD may be blended by primary suppliers into their distillate pool in order to meet their renewable content obligations under the Regulations while meeting industry-accepted standards. (see footnote 12) Despite the current price premium for HDRD over biodiesel, some primary suppliers have chosen to blend HDRD since it requires minimal infrastructure investments to blend and has a more favourable cloud point and cetane number than biodiesel. (see footnote 13), (see footnote 14) The lower capital investment required for HDRD blending is particularly important for Eastern Canada, which has not historically had any provincial regulatory requirements for renewable content in diesel fuel or heating distillate oil, and has access to international supplies of HDRD through shipping ports in the Maritimes and Quebec.

HDRD is expected to compose 91% of renewable content blended in Eastern Canada in the medium term and 81% in the long term. The renewable content reductions owing to the space heating exemption are expected to constitute a 14% reduction in renewable content obligations for Eastern Canada in 2013. (see footnote 15) In this analysis, the renewable content reductions resulting from the Amendments are assumed to be reductions in HDRD imports. This assumption is analyzed in the sensitivity analysis in section 7.7.1.

HDRD feedstock composition

Based on compliance data, and considering fluctuations since the Regulations came into force in 2011, a reasonable base case estimate for the feedstock composition of HDRD imports is 70% palm-based and 30% tallow-based. This proportion is maintained for volumes of HDRD in this analysis, but the sensitivity analysis varies this proportion to examine how sensitive the cost-benefit analysis results are to this assumption.

HDRD prices

Prices for HDRD were assumed to be approximately 40¢/L higher than diesel prices in 2013, based on the best available information from industry experts and stakeholder consultations. It is expected that the HDRD supply will increase in the coming years as additional production comes online, and the price is thus expected to fall. Based on industry experts, the HDRD price premium over diesel is assumed to decrease from 40¢/L to 30¢/L over the next five years, which is roughly on par with the current price premium for biodiesel over diesel. The HDRD price is assumed to maintain a 30¢/L margin over diesel for the remainder of the forecast period. A sensitivity analysis was employed to examine the sensitivity of the expected net benefits to this assumption.

Incremental kerosene volumes

The RIAS for the Regulations Amending the Renewable Fuels Regulations published in the Canada Gazette, Part II, on July 20, 2011, assumed for the base case of the analysis that primary suppliers would be required to blend volumes of kerosene into blends of biodiesel and petroleum diesel. This assumption followed from the relatively high cloud point of biodiesel fuels relative to petroleum diesel and the cold Canadian winter climate. (see footnote 16) Primary suppliers, however, have chosen to blend HDRD year-round and primarily canola-based biodiesel during the warmer months. (see footnote 17) This almost completely reduces the need for kerosene blending to improve the cold-flow properties of blended fuel. The RIAS therefore assumes that there will be no incremental change to kerosene purchases or use following the reduced renewable content blending obligations resulting from these Amendments.

Incremental capital, operating, maintenance, and administrative costs

In order to comply with the Regulations, primary suppliers need the appropriate infrastructure in place to blend either biodiesel or HDRD into their distillate pools. The Amendments should not affect capital investments or operating and maintenance costs for primary suppliers of distillate since they will continue to be required to comply with their renewable content blending obligations for diesel fuel and heating distillate oil not for space heating. The six-month exemption extension for Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and Prince Edward Island may result in a six month delay of infrastructure upgrades, the costs and benefits for which are assumed to be nil. Administrative costs are also not expected to change since primary suppliers must continue to submit reports under the Renewable Fuels Regulations.

As outlined above, expected trends related to regulatory compliance behaviour and consultation with industry and government experts have informed the following assumptions used for the period 2013–2035 of this cost-benefit analysis:

Table 1: Key variables and assumptions (see footnote 18)

| Key variable |

Assumption |

Sensitivity analysis (see 7.7.1) |

|---|---|---|

Renewable content blending |

All renewable content blended with diesel fuel |

Not conducted (see above) |

Renewable content composition |

Met entirely by reduced HDRD imports |

30, 60, 90% biodiesel |

HDRD composition (feedstocks) |

70% palm, 30% tallow |

50% palm, 50% tallow 100% palm, 0% tallow |

HDRD price |

40¢/L over diesel in 2013, falling to 30¢/L by 2018 |

Price premium +/– 30% |

Incremental kerosene volumes |

No expected incremental impact |

Not conducted (see above) |

Incremental capital, operating, maintenance, and administrative costs |

No expected incremental impact |

Not conducted (see above) |

Variables were not tested in the sensitivity analysis if there was insufficient evidence to suggest considerable uncertainty or likely alternative scenarios.

7.3. Analytical scenarios

The analysis considers two analytical scenarios: a business as usual scenario (BAU) where the Amendments are not implemented, and a regulatory scenario where the Amendments are implemented. The difference between the two scenarios provides an estimate of the incremental impacts of the Amendments. The two scenarios are based on the same energy demand and price forecasts for 2013–2035 and are limited in scope to the specific volumes of distillate relevant to the Amendments. Both scenarios reflect recent information and expected trends regarding the compliance behaviour of primary suppliers in response to their renewable content obligations under the Renewable Fuels Regulations.

7.3.1. Business as usual scenario

In this baseline scenario, refiners would be required to blend renewable fuel to meet the renewable content requirements for volumes of distillate that would otherwise be exempt under the Amendments. Recent trends suggest the renewable content blended would likely have been almost exclusively HDRD in the short to medium term, and this assumption is held throughout the analytical time frame. (see footnote 19) The lower energy content per litre of HDRD relative to petroleum diesel would have entailed additional fuel purchases by consumers to satisfy their total energy demand. (see footnote 20)

7.3.2. Regulatory scenario

The regulatory scenario is defined by the implementation of the Amendments; petroleum diesel will replace the renewable content that would have otherwise been required. Less fuel is expected to be required to meet the total energy demand since diesel has a higher energy content per litre than does HDRD, meaning fuel savings for consumers. Since petroleum diesel generally has higher lifecycle GHG emissions than do renewable alternatives, GHG emissions are estimated to be higher in the regulatory scenario.

7.4. Modelling and data

Heating distillate oil and diesel demand forecasts were required to estimate the expected reduction of renewable content as a result of these Amendments. Fuel characteristics such as energy content, GHG emissions factors, and prices were also required to complete the cost-benefit analysis. A social cost of carbon was used to estimate socioeconomic damages due to GHG emissions.

7.4.1. Heating distillate oil demand forecast

Environment Canada’s Energy-Economy-Environment Model for Canada (E3MC) was used to forecast volumes of heating distillate oil for 2013–2035 and volumes of diesel fuel for 2013. E3MC is an end-use model that incorporates historical data from the National Inventory Report published by Environment Canada.

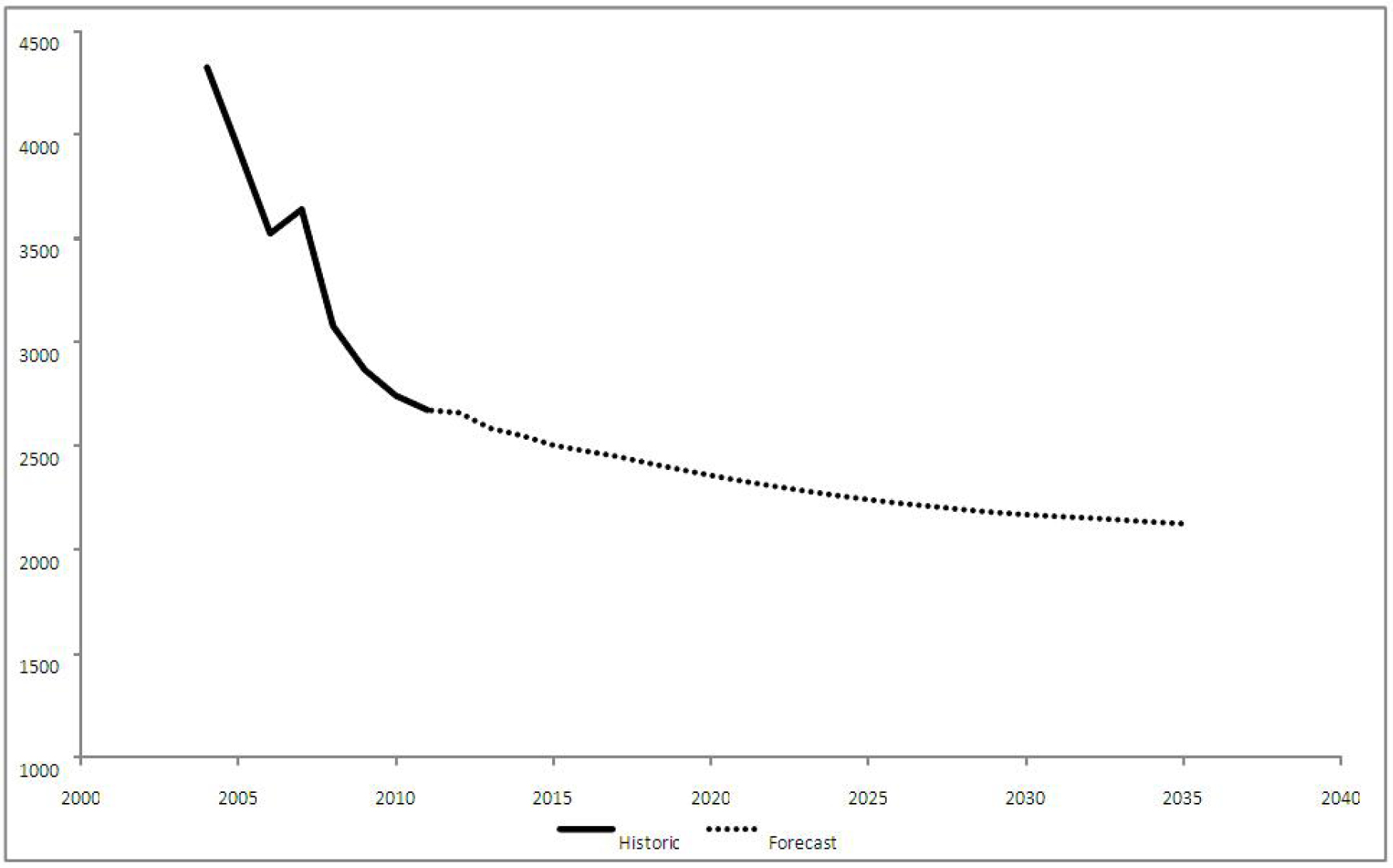

The volume of diesel fuel used for space heating purposes is negligible, so only a forecast of heating distillate oil for space heating purposes was necessary for the analysis of the national space heating exemption. Figure 1 shows the demand for heating distillate oil for space heating purposes nationally, excluding Newfoundland and Labrador and the Territories, historical data to 2011, and forecast for 2012–2035, as described above. Demand for heating distillate oil is expected to fall as a result of changing market dynamics. For example, natural gas as a heating alternative has become increasingly attractive, in part due to lower natural gas prices following the shale gas boom in North America.

Figure 1: Demand for heating distillate oil for space heating purposes (ML) (see footnote 21)

Source: E3MC, July 2013; ML = megalitres.

7.4.2. Relevant distillate volumes

Only certain volumes of diesel fuel and heating distillate oil are relevant to the analysis of the Amendments.

For the national space heating exemption, relevant volumes of heating distillate oil are those used for space heating purposes over 2013–2035 for British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Ontario, Quebec, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, and Prince Edward Island. (see footnote 22)

For the Maritimes exemption extension, relevant volumes of diesel fuel are those sold for or delivered for use in the Maritime provinces during the first half of 2013. This was estimated by multiplying the forecasted demand by the proportion of diesel fuel sold in these provinces between January 1 and June 30, 2012. (see footnote 23) Volumes of heating distillate oil not used for space heating purposes in these provinces in 2013 were accounted for by dividing their forecast annual volume in half. (see footnote 24)

7.4.3. Renewable content volumes

The Renewable Fuels Regulations require 2% renewable content based on the pre-blended volumes of diesel fuel and heating distillate oil subject to the Regulations. Total final blended product will therefore average 1.96% renewable content. (see footnote 25) To determine the reduction in renewable content volumes, the relevant volumes of distillates were multiplied by 1.96%. (see footnote 26), (see footnote 27)

7.4.4. Fuel energy content

HDRD has roughly a 5.5% lower average volumetric energy density than petroleum diesel. (see footnote 28) Table 2 shows the average energy density of petroleum diesel, biodiesel from canola, and HDRD from palm and tallow feedstocks in megajoules per litre (MJ/L). The energy density of these fuels was used to determine the volume of fuel required to meet forecasted energy demand. (see footnote 29)

Table 2: Average energy density of select fuels (see footnote 30)

Fuel type |

Energy density (MJ/L) |

|---|---|

Petroleum diesel |

38.653 |

HDRD (from palm) |

36.511 |

HDRD (from tallow) |

36.511 |

Biodiesel (from canola) |

35.400 |

7.4.5. Fuel GHG emissions factors

Life cycle emission factors for diesel fuel and HDRD (from palm and tallow) were estimated using the Natural Resources Canada (NRCan) GHGenius model, version 4.02a, under average Canadian conditions, in order to inform estimates of incremental GHG emissions due to the Amendments. (see footnote 31) The GHG emission factors used in this analysis are presented in Table 3 below (e.g. in the case of diesel, 1 L of petroleum diesel used in an internal combustion engine results in approximately 3.506 kg of CO2e emissions on a life cycle basis, which accounts for all emissions from production to combustion). These emissions factors are used to determine emissions from fuel consumed in both the business as usual and regulatory scenarios.

Table 3: GHG emissions factors for select fuels (see footnote 32)

Fuel type |

Emissions (kgCO2e/L) |

|---|---|

Petroleum diesel |

3.506 |

HDRD (from palm) |

1.877 |

HDRD (from tallow) |

0.544 |

Biodiesel (from canola) |

0.522 |

7.4.6. Diesel prices

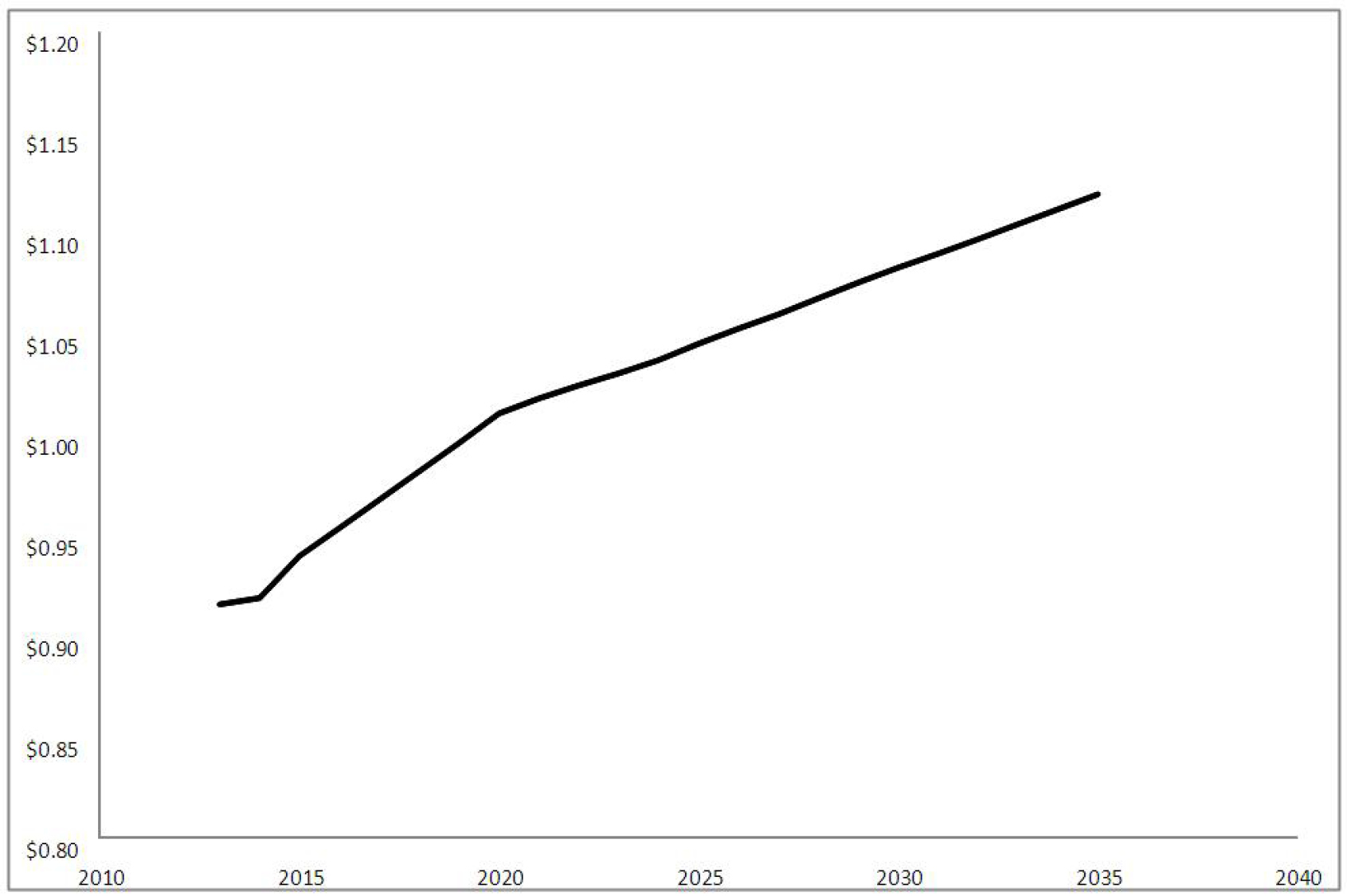

Using E3MC, pre-tax retail diesel price projections were forecast for 2013–2035, which incorporates the National Energy Board (NEB) forecast for the West Texas Intermediate crude oil price as reported in the NEB’s Canada’s Energy Future: Energy Supply and Demand Projections to 2035 — Market Energy Assessment. (see footnote 33) E3MC uses this data to generate fuel price forecasts which are primarily based on consumer-choice modelling and historical relationships between macroeconomic and fuel price variables. To estimate wholesale diesel prices, the pre-tax diesel prices were reduced by a 2012 national average marketing operating margin of 9.7¢/L retrieved from Kent Marketing Services. (see footnote 34) Figure 2 below shows the pre-tax wholesale diesel price forecast for 2013–2035.

Figure 2: Pre-tax, wholesale diesel price per litre in 2012 Canadian dollars

Source: E3MC, July 2013.

7.4.7. Social cost of carbon

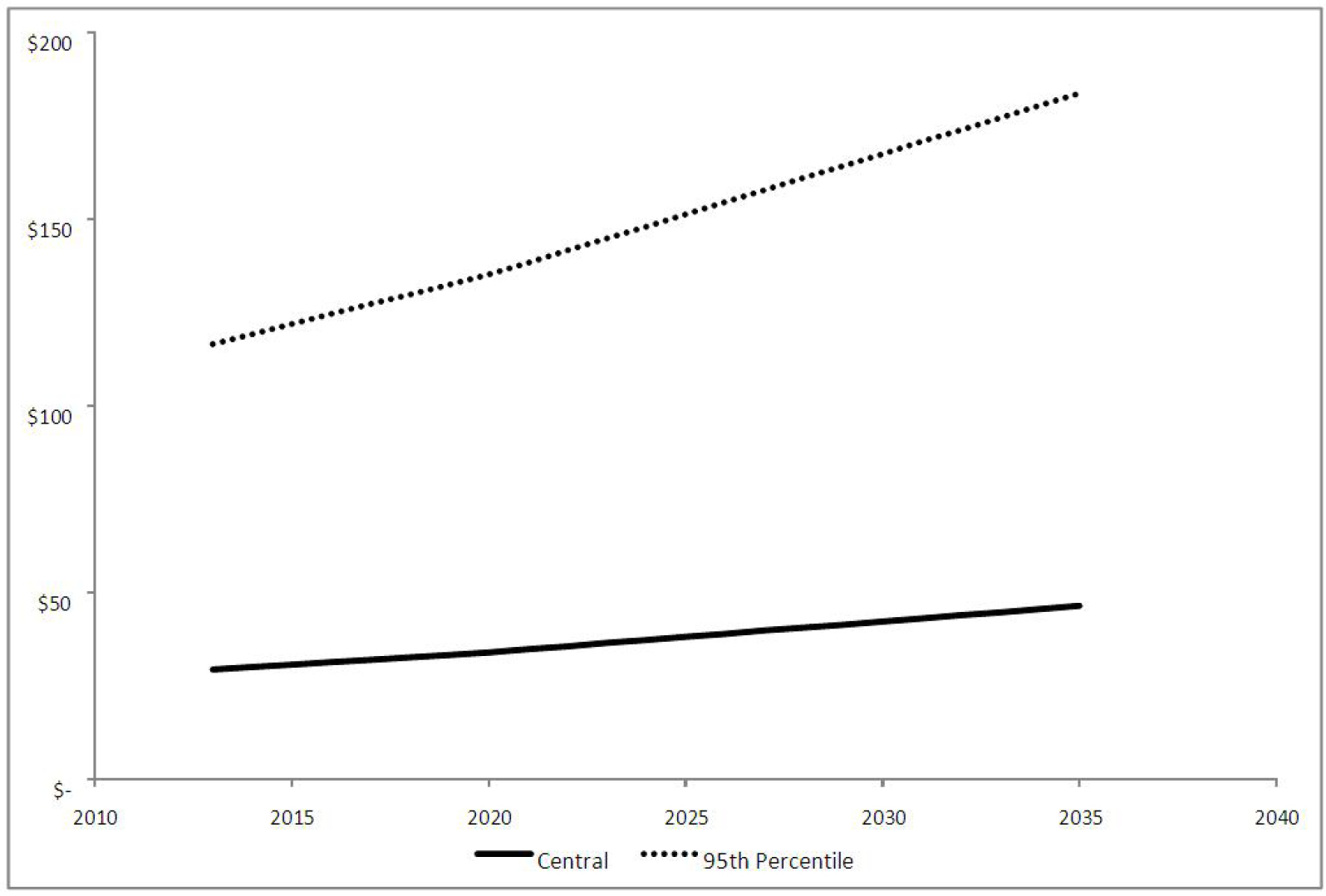

The estimated value of avoided damages from GHG reductions is based on the climate change damages avoided at the global level. These damages are usually referred to as the social cost of carbon (SCC). Estimates of the SCC between and within countries vary widely due to challenges in predicting future emissions, climate change, damages and determining the appropriate weight to place on future costs relative to near-term costs (discount rate) and foreign damages relative to domestic damages.

The SCC values used in this assessment draw on ongoing work undertaken by Environment Canada (see footnote 35) in collaboration with a federal interdepartmental working group, and in consultation with a number of external academic experts. This work involves reviewing existing literature and other countries’ approaches to valuing GHG emissions.

With the preliminary recommendations, based on current literature and in line with the approach adopted by the United States Interagency Working Group on the Social Cost of Carbon, (see footnote 36) it is reasonable to estimate SCC values at $29.38/tonne of CO2e in 2013, increasing each year with the expected growth in damages. (see footnote 37) Environment Canada’s review also concludes that a value of $116.45/tonne in 2013 should be considered, reflecting arguments raised by Weitzman (2011) (see footnote 38) and Pindyck (2011) (see footnote 39) regarding the treatment of right-skewed probability distributions of the SCC in cost-benefit analyses. (see footnote 40) Their argument calls for full consideration of low probability, high-cost climate damage scenarios in cost-benefit analyses to more accurately reflect risk. A value of $116.45/tonne does not, however, reflect the extreme end of SCC estimates, as some studies have produced values exceeding $1,000/tonne of carbon emitted.

The federal interdepartmental working group on SCC also concluded that it is necessary to continually review the above estimates in order to incorporate advances in physical sciences, economic literature, and modelling to ensure the SCC estimates remain current. Environment Canada will continue to collaborate with the federal interdepartmental working group and outside experts to review and incorporate, as appropriate, new research on SCC in the future.

Figure 3: SCC estimates (2012 Canadian dollars per tonne)

Source: Federal interdepartmental working group on the social cost of carbon.

7.5. Benefits

The Amendments are expected to result in primary supplier and consumer fuel savings due to the reduced renewable content requirements. Primary suppliers have demonstrated a preference to almost exclusively create blends with diesel fuel to meet their renewable content obligations for both diesel fuel and heating distillate oil. This suggests that renewable content reductions resulting from these Amendments will be replaced by less expensive diesel fuel, resulting in fuel cost savings for suppliers. Diesel also has slightly higher energy content than renewable fuel, meaning that consumers should need less fuel to meet their energy demands, resulting in direct fuel savings for consumers. (see footnote 41)

7.5.1. Supplier fuel cost savings

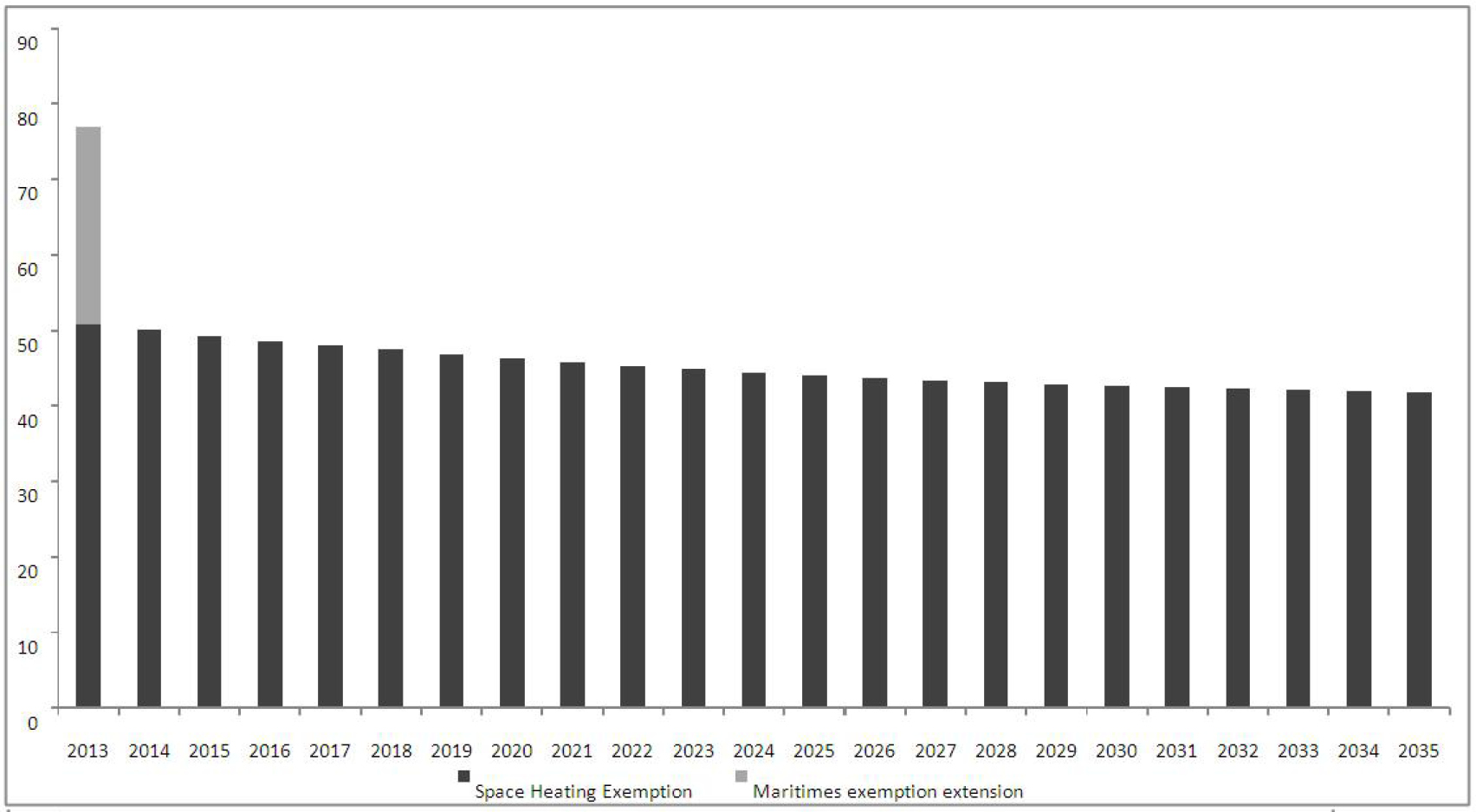

The Amendments reduce the renewable content obligations for primary suppliers of diesel fuel and heating distillate oil to the Maritimes in 2013, and for primary suppliers of heating distillate oil for space heating purposes nationally from 2013 onwards. Figure 4 shows the estimated incremental reduction in renewable content as a result of the Amendments. (see footnote 42) The decreasing trend in incremental reductions in renewable content over the period 2013–2035 reflects the forecasted decrease in relevant heating distillate oil demand, as shown previously in Figure 1. The incremental reductions from the Maritimes exemption extension are assumed to occur in 2013, although the extended compliance period for 2013–2014 may imply some reallocation across these two years.

Figure 4: Yearly incremental reductions in renewable content (ML) (see footnote 43)

Source: Modelling results as described in sections 7.4.1 to 7.4.4; ML = megalitres.

Cost reductions are expected to be realized due to reduced imports of HDRD. These will be partially offset by increased diesel purchases to replace the volume of renewable fuel reduced. (see footnote 44) The net result will be fuel cost savings to suppliers, as shown in Table 4 below.

The present value of cost reductions from reduced HDRD imports as a result of the space heating exemption is estimated to be $1,030.3 million for 2013–2035. The cost of increased diesel purchases over this period is estimated to be $784.2 million, resulting in net supplier fuel cost savings of $246.1 million for the space heating exemption.

The Maritimes exemption extension is expected to result in cost reductions from reduced HDRD imports estimated at $34.5 million in 2013. The cost of increased diesel purchases is estimated to be $24.0 million in 2013, resulting in net supplier fuel cost savings of $10.5 million from the Maritimes exemption extension.

Overall, the Amendments are expected to result in net supplier fuel cost savings, over the period 2013–2035, estimated at a present value of $256.6 million.

Table 4: Incremental supplier fuel cost savings, in millions of 2012 Canadian dollars

Fuel savings (and offsetting costs) |

2013 |

2023 |

2035 |

2013–2035 (PV) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Space heating exemption |

||||

HDRD import cost reductions |

66.7 |

59.6 |

59.2 |

1,030.3 |

Cost of increased diesel purchases |

(46.4) |

(46.2) |

(46.7) |

(784.2) |

Net fuel cost savings |

20.3 |

13.4 |

12.5 |

246.1 |

Maritimes exemption extension |

||||

HDRD import cost reductions |

34.5 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

34.5 |

Cost of increased diesel purchases |

(24.0) |

(0.0) |

(0.0) |

(24.0) |

Net fuel cost savings |

10.5 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

10.5 |

Total net fuel cost savings |

30.8 |

13.4 |

12.5 |

256.6 |

Note: Due to rounding, some of the totals may not match; PV = present value discounted to 2013 at a 3% discount rate.

In this analysis, net supplier fuel cost savings represent avoided costs of the current Regulations, and some of this benefit may be passed onto consumers of diesel fuel or heating distillate oil.

7.5.2. Consumer fuel savings

A 1.96% final blend of HDRD in diesel constitutes a 0.11% reduction in energy content per litre compared to the average energy content of petroleum diesel. On an individual basis, this reduction in volumetric energy content would not result in a noticeable increase in fuel consumption. At the national level, however, much larger volumes of fuel are considered, and it is important to account for this small energy difference.

The Amendments will see some renewable content replaced by petroleum diesel. The result is some cost savings to Canadian end-users since less purchased diesel volume will be required in order to meet the same total energy demand. Reduced fuel purchases from the space heating exemption are expected to be about 57.5 ML for 2013–2035, with an estimated present value of $47.6 million. (see footnote 45) The Maritimes exemption extension is expected to result in reduced fuel purchases of about 1.5 ML in 2013, with cost savings estimated at a present value of $1.5 million. The total present value of reduced fuel purchases as a result of these Amendments is estimated to be $49.1 million, as shown in Table 5 below.

Table 5: Reduction in fuel purchases, in millions of 2012 Canadian dollars

| 2013 |

2023 |

2035 |

2013–2035 (PV) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

Space heating exemption |

2.8 |

2.8 |

2.8 |

47.6 |

Maritimes exemption extension |

1.5 |

0 |

0 |

1.5 |

Total incremental benefit |

4.3 |

2.8 |

2.8 |

49.1 |

Note: Due to rounding, some of the totals may not match; PV = present value discounted to 2013 at a 3% discount rate.

7.5.3. Total benefits

The present value of total benefits from the space heating exemption from the Renewable Fuels Regulations is estimated to be $293.7 million. The Maritimes exemption extension is expected to result in a present value of total benefits estimated at $12.0 million. The total benefits from the Amendments are thus estimated to be $305.7 million (present value), as shown in Table 6 below.

Table 6: Total benefits, in millions of 2012 Canadian dollars

| 2013 |

2023 |

2035 |

2013–2035 (PV) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

Space heating exemption |

23.1 |

16.2 |

15.3 |

293.7 |

Maritimes exemption extension |

12.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

12.0 |

Total benefits |

35.1 |

16.2 |

15.3 |

305.7 |

Note: Due to rounding, some of the totals may not match; PV = present value discounted to 2013 at a 3% discount rate.

7.6. Costs

The Amendments are expected to result in foregone GHG emissions reductions due to the reduced renewable content requirements for primary suppliers. These GHG emissions are the main quantified cost in this analysis, and are monetized using a social cost of carbon of about $29 per tonne in 2013.

7.6.1. Foregone GHG emissions reductions

GHGenius life cycle assessment (LCA) modelling (see footnote 46) estimated that GHG emissions by volume are higher for petroleum diesel than for HDRD. The Amendments will result in reduced HDRD content and increased petroleum content in diesel fuel, resulting in an increase in GHG emissions. This will be partially offset by an overall reduction in fuel purchases since the diesel pool will include less renewable content, which has lower energy content. The net result is expected to be an increase in GHG emissions due to these Amendments.

As a result of the space heating exemption, it is estimated that the foregone GHG emissions reductions will be 1.90 Mt over the period 2013–2035, or less than 0.10 Mt per year. The Maritimes exemption extension is estimated to result in approximately 0.05 Mt in GHG emissions in 2013. For the period 2013–2035, the Amendments are expected to result in a total of approximately 2.0 (1.95) Mt of GHG emissions, as shown in Table 7 below.

Table 7: Incremental GHG emissions, in millions of tonnes (Mt CO2e)

| 2013 |

2023 |

2035 |

2013–2035 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

Space heating exemption |

0.09 |

0.08 |

0.08 |

1.90 |

Maritimes exemption extension |

0.05 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.05 |

Total incremental emissions |

0.14 |

0.08 |

0.08 |

1.95 |

Note: Due to rounding, some of the totals may not match.

The incremental GHG emissions that are estimated to result from the Amendments are monetized in Table 8 below, based on the central value for the social cost of carbon of $29 in 2013 (and increasing thereafter), as shown previously in Figure 3.

The present value of total costs from the space heating exemption from the Renewable Fuels Regulations is estimated to be $51.3 million. The present value of total costs from the Maritimes exemption is estimated at $1.4 million. The total costs from the Amendments are thus estimated to be $52.7 million (present value) based on the central value for the social cost of carbon. The results are presented below in Table 8.

Table 8: Incremental GHG emissions, in millions of 2012 Canadian dollars

| 2013 |

2023 |

2035 |

2013–2035 (PV) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

Space heating exemption |

2.7 |

3.0 |

3.6 |

51.3 |

Maritimes exemption extension |

1.4 |

0 |

0 |

1.4 |

Total incremental cost |

4.1 |

3.0 |

3.6 |

52.7 |

Note: Due to rounding, some of the totals may not match; PV = present value discounted to 2013 at a 3% discount rate.

7.7. Summary of costs and benefits

For the period 2013–2035, the present value of total benefits is estimated at $306 million from direct fuel cost savings for industry ($257 million) and consumers ($49 million). The present value of total costs is estimated at $53 million, based on foregone GHG emissions reductions of 2.0 million tonnes (megatonnes) valued at a social cost of carbon of about $29 per tonne in 2013. The present value of net benefits is estimated at $253 million over 23 years, with benefits outweighing costs by a ratio of almost six to one. The results of the cost-benefit analysis of the Amendments are presented in Table 9.

Table 9: Summary of main results, in millions of 2012 Canadian dollars

| Incremental costs and benefits (million 2012 CAN$) |

Base Year: 2013 |

2023 |

Final Year: 2035 |

Total 23 Year (PV) 2013–2035 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Quantified industry benefits |

||||

Supplier fuel cost savings |

30.8 |

13.4 |

12.5 |

256.6 |

Quantified consumer benefits |

||||

Consumer fuel cost savings |

4.3 |

2.8 |

2.8 |

49.1 |

Total benefits |

35.1 |

16.2 |

15.3 |

305.7 |

Quantified social costs |

||||

GHG emissions (SCC at $29/tonne) |

4.1 |

3.0 |

3.6 |

52.7 |

Total costs |

4.1 |

3.0 |

3.6 |

52.7 |

Net benefit (SCC at $29/tonne) |

30.9 |

13.2 |

11.8 |

253.0 |

Net benefit (alternate SCC at $116/tonne) |

18.6 |

4.3 |

1.3 |

96.5 |

Benefit-to-cost ratio (SCC at $29/tonne) |

8.5 |

5.4 |

4.3 |

5.8 |

GHG emissions (Mt CO2e) |

0.1 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

2.0 |

Note: Due to rounding, some of the totals may not match; PV = present value discounted to 2013 at a 3% discount rate.

7.7.1. Sensitivity analysis

Several sensitivity analyses were completed to consider the impact of uncertainty in key variables. For the sensitivity analyses examined, the Amendments demonstrate positive expected net benefits ranging from $43.8 to $328.9 million and foregone GHG emissions reductions ranging from 0.7 to 3.0 Mt. The results are presented below.

Sensitivity to renewable content composition

The Regulatory Impact Analysis (RIAS) for the Amendments to the Renewable Fuels Regulations,published in the Canada Gazette, Part II, on July 20, 2011, (see footnote 47) assumed that, nationally, for 2012–2035, 90% of incremental demand would be met by domestic production of biodiesel and 10% by imports of HDRD. Primary suppliers of distillate to Eastern Canada currently favour HDRD imports, (see footnote 48) and the base case of this analysis assumes that 100% of renewable content reductions as a result of these Amendments will be reductions in HDRD. A sensitivity analysis on this assumption was completed, with the results presented below in Table 10.

The biodiesel volumes analysed in the sensitivity analysis are assumed to be canola-based. The majority of biodiesel blending in Canada occurs in Western Canada, of which a significant portion is canola-based biodiesel. As well, significant additional domestic production capacity of canola-based biodiesel in Western Canada is expected in the near future. If biodiesel blending to meet renewable content obligations for primary suppliers of distillate to Eastern Canada were to occur, the expected least-cost approach would be additional blending of canola-based biodiesel in Western Canada, either through the trading of compliance units or use of within-company distillate pool averaging. (see footnote 49)

Although both biodiesel and HDRD have lower energy content per litre relative to petroleum diesel, biodiesel has more favourable lubricity than HDRD and petroleum diesel. (see footnote 50), (see footnote 51) The additional fuel lubricity from biodiesel at low level blends works to improve engine efficiency and offset the effect of lower energy density on fuel consumption; therefore, no volume adjustments to account for energy content differences were made for biodiesel volumes in the sensitivity analysis.

Table 10: Sensitivity to renewable fuel composition, net benefit in millions of 2012 Canadian dollars, GHG emissions in Mt CO2e

description |

Net Benefit (PV) |

GHG Emissions |

|---|---|---|

Base case — 100% HDRD |

253.0 |

2.0 |

70% HDRD, 30% biodiesel (from canola) |

223.3 |

2.3 |

40% HDRD, 60% biodiesel (from canola) |

193.6 |

2.7 |

10% HDRD, 90% biodiesel (from canola) |

163.9 |

3.0 |

Note: PV = Present value discounted to 2013 at a 3% discount rate.

Sensitivity to HDRD feedstock mix

The base case assumes a feedstock contribution to HDRD volumes of 70% palm and 30% tallow. To test the sensitivity of the results of the cost-benefit analysis to the assumption of HDRD feedstock mix, a scenario with 100% palm and 0% tallow and a scenario with 50% palm and 50% tallow were examined. The results are presented below in Table 11.

Table 11: Sensitivity to HDRD feedstock mix, net benefit in millions of 2012 Canadian dollars, GHG emissions in Mt CO2e

description |

Net Benefit (PV) |

GHG Emissions |

|---|---|---|

Base case — 70% palm, 30% tallow |

253.0 |

2.0 |

100% palm, 0% tallow |

264.5 |

1.5 |

50% palm, 50% tallow |

245.4 |

2.2 |

Note: PV = Present value discounted to 2013 at a 3% discount rate.

Sensitivity to biodiesel price premium

The base case for the RIAS assumed that the biodiesel premium over diesel is and will remain 30¢/L over the period of analysis, while the HDRD premium over biodiesel will be 10¢/L in 2013, falling to 0¢/L over the next five years. Three alternative cases were tested where the price premium for biodiesel over diesel falls from 30¢/L in 2013 to 0¢/L by 2035, 2025, or 2015. In all cases, the HDRD price premium over biodiesel remained unchanged, whereby the HDRD price matches the biodiesel price by 2018. The results are presented below in Table 12.

Table 12: Sensitivity to biodiesel price premium, in millions of 2012 Canadian dollars

description |

Net Benefit (PV) |

|---|---|

Base case — 30¢/L biodiesel premium 2013–2035 |

253.0 |

Alternative case 1 — biodiesel premium falls from 30¢/L in 2012 to 0¢/L in 2035 |

154.9 |

Alternative case 2 — biodiesel premium falls from 30¢/L in 2012 to 0¢/L in 2025 |

106.4 |

Alternative case 3 — biodiesel premium falls from 30¢/L in 2012 to 0¢/L in 2015 |

43.8 |

Note: PV = Present value discounted to 2013 at a 3% discount rate.

Sensitivity to GHG emissions factors

A sensitivity analysis was conducted on the emissions factors shown in Table 3 to consider the impact on net benefits and GHG emissions. The GHG emissions factor for each renewable fuel was set equal to petroleum diesel (zero change in emissions) and the results are presented below in Table 13.

Table 13: Sensitivity to GHG emissions factors, net benefit in millions of 2012 Canadian dollars, GHG emissions in Mt CO2e

description |

Net Benefit (PV) |

GHG Emissions |

|---|---|---|

Base case |

253.0 |

2.0 |

0% GHG emissions reductions from palm-based HDRD relative to petroleum diesel |

285.8 |

0.7 |

0% GHG emissions reductions from tallow-based HDRD relative to petroleum diesel |

278.5 |

1.0 |

0% GHG emissions reductions from canola-based biodiesel relative to petroleum diesel |

253.0 |

2.0 |

Note: PV = Present value discounted to 2013 at a 3% discount rate.

The base case analysis assumes 100% HDRD, comprising 70% palm-based and 30% tallow-based HDRD. Since the base case analysis assumes that no canola-based biodiesel will be affected by the Amendments, varying this GHG emission factor has no impact on the results.

Additional sensitivity analysis

Some additional sensitivity analyses were conducted, including sensitivity to diesel and heating oil demand, the HDRD price premium, and the discount rate. The results are presented below in Table 14.

Table 14: Sensitivity analysis, in millions of 2012 Canadian dollars

description |

Net Benefit (PV) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity variables |

Lower |

Central |

Higher |

Sensitivity to diesel and heating oil demand (–30%, central, +30%) |

177.1 |

253.0 |

328.9 |

Sensitivity to HDRD price premium over diesel (–30%, central, +30%) |

176.0 |

253.0 |

330.0 |

Sensitivity to discount rates (7%, 3%, undiscounted) |

189.9 |

253.0 |

330.4 |

Note: PV = Present value discounted to 2013 at a 3% discount rate.

7.7.2. Quantified impacts

Foregone GHG emissions reductions: The Amendments are expected to result in foregone GHG emissions reductions as a result of the increased GHG emissions from diesel relative to HDRD on a lifecycle basis. The foregone GHG emissions reductions are estimated at less than 0.1 Mt per year on average, and total 2.0 Mt over the period 2013–2035.

Reduction in HDRD imports: The Amendments are expected to result in a reduction in HDRD imports in response to the reduced renewable content obligations that primary suppliers will be required to meet. HDRD imports are estimated to be reduced by 1 064.2 ML over the period 2013–2035.

7.8. Non-quantified impacts

7.8.1. Air quality and health impacts

Given the size and nature of the air quality emissions changes expected from these Amendments, the impacts of these emission changes on human health are expected to be minimal. This expectation is consistent with a recent analysis conducted by Health Canada of similarly small air quality emission reduction scenarios.

The potential Canadian air quality and health impacts resulting from changes in mobile sector emissions due to biodiesel use were examined by Health Canada in 2011 for the Regulations Amending the Renewable Fuels Regulations. These 2011 Amendments, which require renewable fuel content in the Canadian diesel pool, are expected to change air pollution emissions from vehicles. Analysis of national on-road vehicle use of biodiesel blends in Canada suggested very minimal impacts on mean ambient concentrations of PM2.5, tropospheric ozone (O3), carbon monoxide (CO), nitrogen dioxide (NO2) and sulphur dioxide (SO2) resulting from the 2011 Amendments. The human health implications of these changes in air quality were assessed nationally and indicated that some minimal health benefits would be expected in modelled year 2006, and that these would be reduced even further by 2020. The report is available at www.hc-sc.gc.ca/ewh-semt/pubs/air/biodiesel-eng.php.

HDRD and biodiesel are both renewable fuels, with different emissions profiles. Therefore, the projected emission impacts of the use of HDRD in the regulatory scenario of the 2013 Amendments are not identical to the scenarios assessed by Health Canada. The expected HDRD air quality emission reductions are similar to but smaller than those predicted for biodiesel. Given the relative size of the projected emission reductions, the overall impacts on air quality and health from HDRD use are expected to be smaller than those observed in the Health Canada biodiesel analysis, which were minimal. Any incremental health impacts due to the changes in on-road emissions associated with the 2013 Amendments are therefore expected to be minimal.

7.8.2. Potential domestic biodiesel production

The Amendments will reduce the demand for renewable fuel over the long term; the demand for renewable fuel is expected to decrease by 41.8 ML in 2035 as a result of the Amendments (see Figure 4). This reduced domestic demand for renewable fuel may reduce the domestic market for some biodiesel producers. The cost-benefit analysis assumes that the reduced renewable content will constitute a reduction in HDRD imports to reflect the reality of expected compliance behaviour as outlined with the assumptions used in this analysis.

7.8.3. Agricultural impacts

The agriculture sector is a source of feedstock for the biodiesel industry and can provide canola oil, soybean oil, and tallow for use in biodiesel operations. HDRD imports are responsible for most of the renewable content used in Eastern Canada, so it is assumed that the use of Canadian agricultural feedstock for biodiesel production has been very small in this region. As the Amendments are expected to result in a reduction of HDRD imports, the impact on the agriculture sector in Canada is expected to be minimal.

7.8.4. Contracted volumes

Stakeholders have indicated that some primary suppliers have engaged in HDRD purchase contracts of one to two years. To ensure primary suppliers are not penalized for their efforts to comply with the Renewable Fuels Regulations, the Amendments extend the compliance period for 2013 to two years from one. This is to provide primary suppliers with sufficient additional flexibility to reallocate compliance units throughout the longer compliance period. It is therefore expected that HDRD purchase contracts should not affect the total reductions assumed by the cost-benefit analysis.

7.8.5. Government costs

The Government has incurred costs in order to set up and monitor the regulations requiring 5% renewable content in gasoline. The incremental costs to set up and monitor the 2% requirement in diesel fuel and heating distillate oil were deemed to be negligible. These Amendments modify the 2% requirement and the incremental costs to government are expected again to be negligible.

7.9. Distributional impacts

7.9.1. Competitiveness

The Canadian economy is highly integrated with the U.S. economy. The Renewable Fuels Regulations continue to require 2% renewable content for volumes of diesel fuel as prescribed in the Regulations. The United States have implemented similar requirements for renewable fuel content in diesel. No international competitiveness impacts on the refining industry are anticipated.

The Amendments are intended to alleviate the short-term impact on the competitiveness of blenders and regional refiners and fuel importers in regions that have not been subject to provincial regulations, particularly in the Maritime provinces. The national refiners can make investments strategically in large markets and/or to meet national requirements by capitalizing on investments made in provinces where regulations already exist. The Amendments provide an extended exemption period of six months for suppliers of distillates to the Maritime provinces, and additional flexibility in order to allow further time for industry to meet the requirements.

7.9.2. Renewable fuels facilities

The Amendments are expected to reduce domestic demand for renewable content by 77.0 ML in 2013 and an average of 44.9 ML annually thereafter. (see footnote 52) Although this reduction in domestic demand for renewable content is expected to be realized by a reduction in HDRD imports, it may also reduce the domestic market for some biodiesel producers. It is not expected that renewable fuel producers will make any change in capital investment decisions as a result of the Amendments.

7.9.3. Supplier fuel costs

Savings (avoided fuel costs) resulting from the reduced renewable content obligations of primary suppliers constitute a benefit to industry. Some of these savings may be passed on to consumers of either diesel fuel or heating distillate oil.

7.9.4. Consumer fuel costs

Overall, the Amendments are expected to mitigate fuel cost increases for Canadians, particularly for those who use oil to heat their homes.

7.9.5. Fuel supply in the Maritimes

The Maritimes region of Canada has an average household income below that of the Canadian average, and a much higher per capita use of heating distillate oil for domestic heating purposes than the Canadian average; in 2011, sales of heating distillate oil in the Atlantic provinces (see footnote 53) were 723 litres per person, compared to 53 litres per person for the remaining Canadian provinces. (see footnote 54) The six-month extension of the exemption for the Maritime provinces from the 2% renewable content requirement in diesel fuel and heating distillate oil will help reduce short-term risks of fuel supply disruptions to this region. The Amendments are thus expected to benefit the Maritimes region.

8. “One-for-One” Rule

The “One-for-One” Rule does not apply to the Amendments, as there is no expected net change in administrative costs to businesses. The Amendments slightly alter some reporting details, but are not expected to impact the overall frequency or intensity of reporting on an ongoing basis. The result is most likely to be no perceptible net change in the administrative burden on businesses.

9. Small business lens

The small business lens does not apply to the Amendments as net costs to small businesses are not expected. Primary suppliers are the only regulatees for which a blending requirement applies, as related to their pool volumes; therefore, they are the only parties measurably and directly affected by the Amendments. Primary suppliers have tended to be large business producers or importers of petroleum fuels and this is not expected to change in the foreseeable future.

10. Consultation

Since 2006, Environment Canada has organized a number of consultation and information sessions with various stakeholders on the proposed regulatory approach for requiring renewable fuel content based on gasoline, diesel fuel and heating distillate oil volumes. A complete description of the consultation process, as well as responses to comments, was provided in the Regulatory Impact Analysis Statement (RIAS) for the Renewable Fuels Regulations published in the Canada Gazette, Part II, on September 1, 2010, as well as in the RIAS for the Regulations Amending the Renewable Fuels Regulations published in the Canada Gazette, Part II, on July 20, 2011.

On December 31, 2012, the Government announced that it intended to propose amendments and Environment Canada subsequently organized stakeholder information sessions and consultations on the proposed Amendments, including the following:

- In January and February 2013, Environment Canada held five information sessions via webinar to communicate the Minister’s announcement, clarify aspects of the proposed Amendments, answer questions and consider comments. At the information sessions, Environment Canada also outlined the next steps in the regulatory development process.

- Environment Canada held a number of meetings and was in communication with individual stakeholders through February 2013 to follow up on questions and comments, and to ensure understanding of the proposed Amendments.

- Environment Canada considered and incorporated further regulatory changes of an administrative nature in the Amendments as a result of comments received from stakeholders on certain provisions that were not included in the Canada Gazette, Part I, prepublication and from implementation issues that were recently brought forward as a result of experiences gained with the completion of the first compliance periods and annual reporting. Environment Canada consulted with stakeholders on these new changes being proposed through the release of a discussion paper, “Environment Canada’s Renewable Fuels Regulations Discussion Paper Proposing Revision of Administrative Provisions,” on July 5, 2013, seeking comments, and with a consultation webinar held July 25, 2013.

CEPA National Advisory Committee (CEPA NAC)

On February 19, 2013, Environment Canada offered to consult with the Canadian Environmental Protection Act National Advisory Committee (CEPA NAC) on the proposed Amendments. CEPA NAC had 60 days from that date to accept the offer to consult. CEPA NAC members did not have any comments on the proposed Amendments.

Comments received following prepublication of the proposed Regulations in the Canada Gazette, Part I, on May 18, 2013

The proposed Amendments were prepublished in the Canada Gazette, Part I, for a 60-day public comment period. During that period, 12 comments were received from parties including the petroleum and renewable fuels industries and their associations, renewable fuel feedstock industries, and auditing firms. Provinces and ENGOs did not comment. No notices of objection were received under subsection 332(2) of CEPA 1999 requesting that a board of review be established under section 333. Comments received touched on many elements of the proposed Amendments, as well as on the Regulatory Impact Analysis Statement (RIAS). A summary of the comments and how they are addressed in the final Regulations is presented below.

Permanent nationwide exemption from the 2% renewable content requirement for heating distillate oil for space heating purposes

Comments were received in support of the exemption from the petroleum industry, but there were concerns expressed regarding changing the Regulations during the time in which industry is in the process of implementing them and it was reiterated that industry requires regulatory certainty and adequate lead time for compliance planning. Comments were also received on the technical language around the exemption wording and concerns about the industry’s ability to identify the ultimate end use of the products they sell as heating distillate oil volumes for space heating purposes, due to the nature of the distribution system.

The renewable fuels and feedstock industries expressed strong opposition to the national exemption for home heating oil. They are concerned that it will erode the mandated renewable fuel volumes and the demand for distillate compliance units, reduce the environmental and economic benefits and increase uncertainty in the market for renewable fuels. Arguments were presented that the costs to consumers are minimal or non-existent. Some commenters also favored increasing the mandated renewable fuel levels, rather than decreasing them.

- The permanent national exemption for diesel fuel or heating distillate oil used for space heating purposes is maintained. Although the Amendments will reduce the overall demand for renewable fuel, the final Regulations will continue to create demand for renewable content in diesel fuel.

- The present value of net benefits is estimated to be $253 million over 23 years, with benefits outweighing costs by a ratio of almost six to one (see section 7 for details).

- The wording of the exemption has been adjusted to address the concerns raised by the petroleum fuel industry.

Six-month extension to the exemption for Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and Prince Edward Island from the 2% renewable content requirement in both diesel fuel and heating distillate oil, ending June 30, 2013

Comments received on the six-month extension to the Maritime exemption were mixed. The renewable fuels and feedstock industries expressed strong opposition, commenting that delaying the implementation of this requirement in this region does not provide additional advantages that could not have been realized in the first exemption period. It was also stated that this extension adds to the uncertainty amongst stakeholders, the media, governments and consumers and hinders the development of a renewable fuels industry in this region. Further comments were made that if the temporary extension is to proceed for the Maritimes, further extensions or permanent exemptions should not be granted.

Some regional members of the petroleum industry commented that the six-month exemption extension should also apply to Quebec and stated concerns about the competitive disadvantages of its exclusion.

Support for extending the exemption in the Maritimes was received from a petroleum association who indicated its members were strongly supportive of the delay and suggested that it be further delayed until there was domestic renewable fuel sources in that region. Some members also preferred a deferral in Quebec as well.

- The final six-month extension to the exemption for Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and Prince Edward Island from the 2% renewable content requirement in both diesel fuel and heating distillate oil, ending June 30, 2013, is maintained. Although the Amendments will reduce the overall demand for renewable fuel, the amended Regulations will continue to create demand for renewable content in diesel fuel.

- The extension will give regulatees supplying distillates to the Maritime provinces more time to make final adjustments to comply with the regulatory requirements.

Extended 24-month second distillate compliance period

Support for extending the second distillate compliance period was received from petroleum fuel stakeholders and a producer of renewable fuel. There were no comments against this provision.

- The Amendments retain the 24-month extended distillate compliance.

Renewable fuel feedstock

One renewable fuel producer requested that the definition of “renewable fuel feedstock” be broadened to include other processes that do not use a renewable feedstock, but use waste byproducts, which result in fuels with lower lifecycle greenhouse emissions.

- Adjusting the definition of “renewable fuel feedstock” is beyond the scope of these Amendments. The definition of “renewable fuel feedstock” was developed based on the definition used by the U.S. EPA in phase 1 of its Renewable Fuel Standard. In general, it covers a broad range of feedstocks recognized as being renewable. Biofuels produced from non-renewable feedstocks are not considered renewable; consequently, no changes were made to the Amendments. Changes to the definition of “renewable fuel feedstock” would require a more substantial consultation with all stakeholders and should be subject to the full regulatory process, including a Canada Gazette, Part I, prepublication.

Administrative changes

General support was received for the various administrative changes proposed in the Canada Gazette, Part I, prepublication, which include more time for recording information and creating records to facilitate more accurate record keeping.

- The Amendments retain the administrative changes as proposed in the Canada Gazette, Part I.

Adoption of improved performance based standards for GHG reductions, biomass sustainability and compliance reporting

Comments were received from a renewable fuel producer that Environment Canada should adopt performance-based standards for GHG reductions, biomass sustainability and compliance reporting, such as minimum GHG reduction and biomass requirements, that are aligned with the U.S.

- The adoption of performance-based standards for GHG reductions, biomass sustainability and compliance reporting are beyond the scope of these Amendments. Any changes in this regard would require substantial consultation with all interested parties. Regulatory changes of this nature would follow the full regulatory process, including a Canada Gazette, Part I, proposal. Environment Canada is aware of and is monitoring actions in other jurisdictions regarding performance-based standards for GHG reductions and sustainability.

- In reference to compliance reporting, Environment Canada intends to publish compliance and performance measurement data in winter 2014. This data will report out on the first compliance period for these Regulations, for which the reporting cycle ended June 30, 2013.

Modification of the definition of “auditor”

Comments from a United States auditing firm requested that Environment Canada amend the definition of “auditor” to allow auditors qualified to prepare annual attestations under the United States Environmental Protection Agency’s Renewable Fuels Standard to be qualified as auditors under these Regulations.